Having completed more than 30 hours of fieldwork in local schools for my education courses, I consider myself well-acquainted with one part of the Lewiston-Auburn community.

Bates senior Claire Brown, meanwhile, has gained her expertise in quite a different area of our community.

Brown, a politics major from Rockville Centre, N.Y., has interned at the Maine District Court in Lewiston since her first year at Bates —including two summers funded by the Harward Center for Community Partnerships — and this year she leveraged that experience to do honors-thesis research on the effectiveness of Maine’s Adult Drug Treatment Courts.

An alternative to jail, drug treatment courts provide multidisciplinary and rehabilitative support for drug-addicted offenders.

Existing in the U.S. since 1989, every state and territory now has a drug court. Maine has five adult drug courts, plus three family treatment drug courts and one for military veterans and civilians who have co-occurring substance abuse disorders and mental illness. For confidentiality reasons, the locations of Brown’s research interviews are not disclosed.

If a student asked you about your thesis, how would you explain it to them?

My thesis is comparing adult drug court to more traditional forms of incarceration and criminal justice in Maine.

Why did you focus on adult drug court vs. a traditional court setting?

Adult drug court is unlike a traditional trial setting where you discuss the matters of the case and then you’re done.

In adult drug court, you see the whole team: the judge, the prosecutor, the probation officer, and the treatment providers. My experience is that they are very invested in the drug court participants’ rehabilitation, about understanding the lives of the people involved, and about building honest relationships with them.

Claire Brown ’17 (center) presents her research on Maine’s Adult Drug Treatment Court system during Mount David Summit on March 31. At left and right are Isobel Curtis and Yarisamar Cortez, fellow presenters about community-engaged research. (Josh Kuckens/Bates College)

The goal of this support is so that when offenders are struggling and relapse, or if they commit some other violation because they are struggling with addiction, they’ll seek help rather than create more problems for themselves.

What inspired your idea?

I wanted to write my thesis on something connected with the community and the court system. During my internship work, I noticed how many cases — whether criminal, family, or other matters — involved parties whose problems were caused in large part by their drug addictions.

I became really interested in the idea of rehabilitation through the court system, specifically the criminal side of drug involvement and the law. And I wanted to study drug court more substantively than it has been before, beyond traditional metrics and end goals such as reducing recidivism, reducing illicit drug use, and saving money in the justice system.

What did you do as a judicial court intern?

My main duty was to digitally record trials, case management conferences, and different proceedings. I also helped the judges review case files. Since I have been doing it for so long, the judges allowed me to write the first draft of some of the court orders.

How did your internship help your thesis work?

It helped me make connections in Maine courthouses. For example, one day, a drug-court prosecutor was in our Lewiston court for a day. Through her, I was able to observe drug court proceedings a few times.

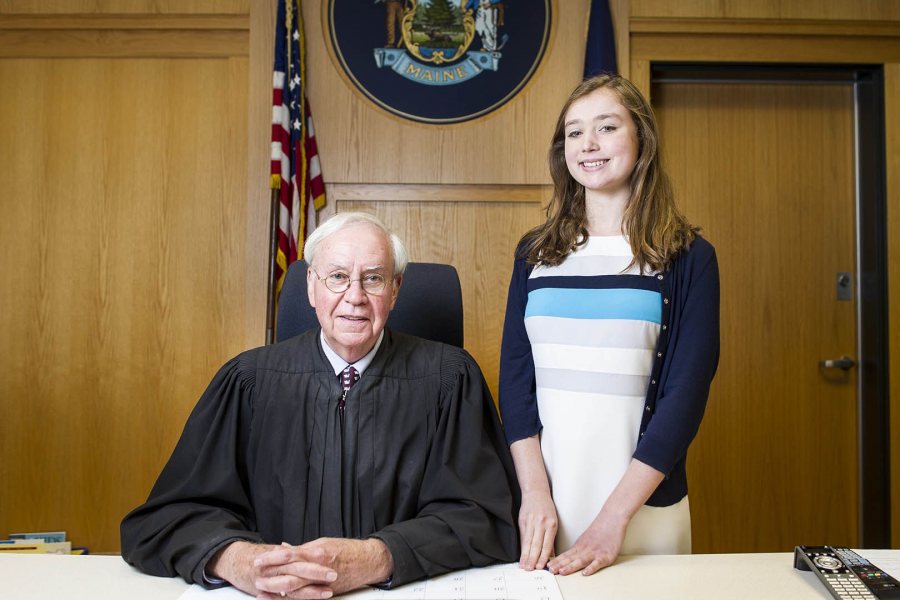

In August 2015, Claire Brown ’17 poses with Judge John Beliveau at the Maine District Court in Lewiston. Her judicial internship, which inspired her honors thesis research on adult drug court effectiveness, was funded in the summers of 2014 and 2015 by the Harward Center for Community Partnerships. (Josh Kuckens/Bates College)

What did you find out?

I found that drug court in Maine is an improvement upon carceral state conceptions of punishment and surveillance as well as success and effectiveness.

What do you mean by “carceral state conceptions of punishment and surveillance”?

The drug court team views the participants as people and not just criminals, so drug court is more rehabilitative than incarceration and probation. The overall focus is on treatment as opposed to punishment and monitoring.

The surveillance used in drug court is more meaningful and humanizing. The intense monitoring of the participant in the community is intended to prepare him or her to live in the community post-drug court — as opposed to being monitored within a controlled environment while incarcerated, or only loosely monitored on probation.

And what does “success and effectiveness” mean in this context?

I mean that the team members did view their results beyond traditional metrics of reducing recidivism and other goals. The team also had rehabilitative notions of success and effectiveness: to better the lives of the participants and equip them with the skills and pro-social connections that will enable them to lead sober, law-abiding lives.

What was your thesis routine?

I usually worked in Coram. I had to code much of the interview data manually, looking for the different themes and connections between the interview data, and I don’t like to sit down for too long, so Coram’s standing workstations helped with that.

What were the ups and downs of your thesis process?

One of the challenges for this project was narrowing the focus on what I was studying. I began by observing four areas when I should have been only observing only two or three. I ultimately settled on surveillance, punishment, and access and bias. The last refers to structural advantages, such as strong family support or employment that may make it easier for some people to succeed both within and following drug court.

It all clicked for me when I actually began witnessing drug court cases in practice and saw all of these factors come together.

On the up side, I earned a Community Engaged Research Fellowship this year from the Harward Center. We had a seminar discussion every other Sunday, and that really helped with some of the history, methods, and ethics of community-engaged research specifically.

I’ve presented my research at the Mount David Summit on campus and at the Engaged Scholarship and Social Justice Conference at Harvard. I learned about the community-based research done by students from other colleges and was able to have meaningful discussions with another student on my panel who had done research related to the War on Drugs.

Can you describe your relationship with your adviser?

My adviser is Associate Professor of Politics Stephen Engel. He’s an expert in constitutional law and American politics. He was always happy to meet with me and offer me advice when I was struggling with the research process.

Were there any moments when you said, “There aren’t enough hours in the day to get this work done!”?

Transcribing the interviews was the most time-intensive part — just listening to all the “uhs” and “ums” and repetitive sentences was really hard. One of my politics professors recommended that I invest in a transcription foot pedal. I should’ve!

What was the most enjoyable part about working on your thesis?

I feel like my thesis is really a culmination of my Bates experience. Graduation is coming up, and I can’t imagine just leaving the court.

I loved doing interviews because it was fascinating to hear the different members of the team involved in drug court describe the trusting relationships they’ve built with participants. That was a very valuable part of my thesis.

What advice would you give to students who will be writing thesis?

The earlier you settle on a topic, have an idea of where you’re going, and start looking at the literature, the better shape you will be in.

And also: Just relax. Thesis is a big project and a daunting project, but also take some time for yourself.

What are your post-grad plans?

I will be working as a project assistant at the law firm Sidley Austin, in New York City. I start in late June.