Some years ago, Greg Boardman heard from someone in Connecticut who wanted to talk about Boardman’s first band.

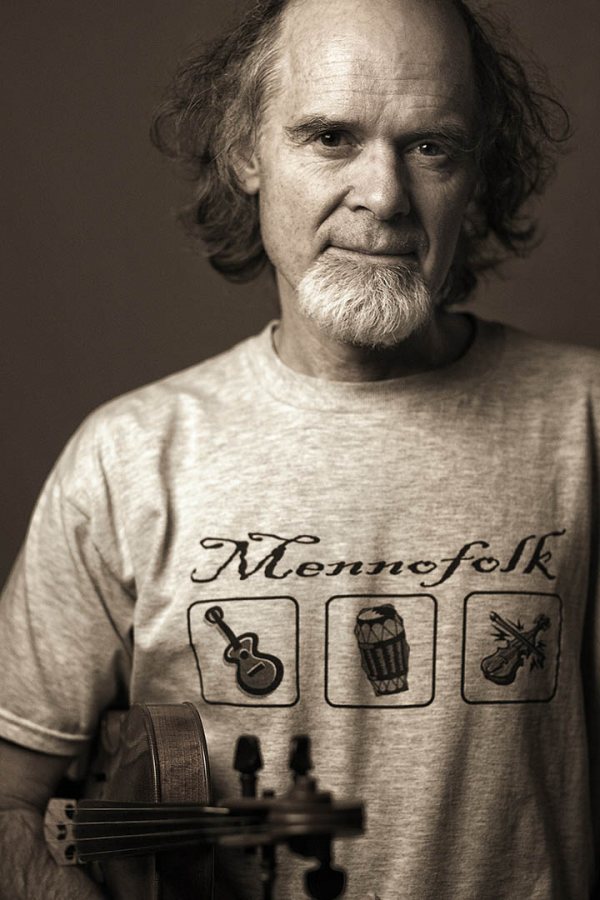

“Man, you got a following down here like you wouldn’t believe!” the caller told Boardman, a member of Bates’ applied music faculty and a folk musician well-known in Maine. “You’ve got a cult following down here!”

If “cult following” was an exaggeration, the call does illustrate the depth of Boardman’s roots in music. The caller was letting him know that Boardman’s first career recording, a single by his band the Rogues, would be included on a CD compilation of New England garage bands.

That single, comprising the Boardman compositions “Next Guy” and “Faces on the Wall,” was released in 1965. (The compilation, an expanded edition of a 1983 LP, is titled New England Teen Scene.)

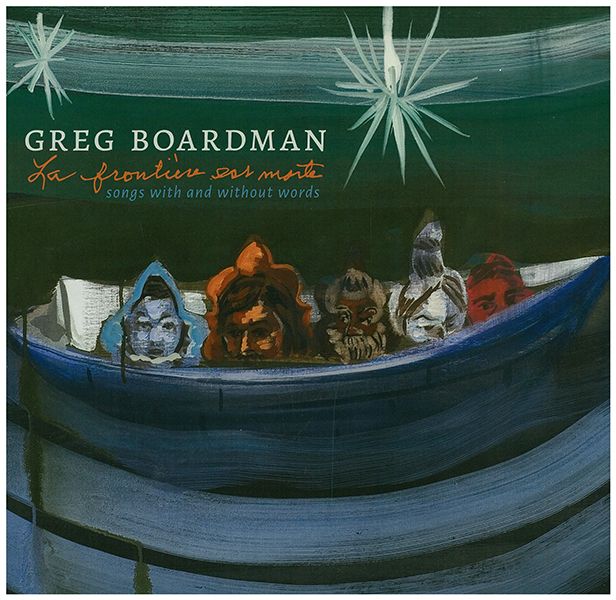

Fifty-two years, a dozen recordings, and countless performances later, Boardman is back on vinyl. He has just released La frontière est morte — Songs with and without words, an LP of original songs and instrumental music, along with a couple of choice cover versions. (Two cuts, “One Soul at a Time” and “The Scapegoat (is innocent)” are posted at Boardman’s Soundcloud site.)

Boardman sings and plays guitar, fiddle, and other strings on the LP. His accompanists include sons Ethan and Aidan; a Bates singing ensemble, the Gospelaires; and multi-instrumentalist Julia Plumb ’05.

Boardman will be accompanied by Plumb and cellist Daniel Hawkins for a record-release concert at 7:30 p.m. Friday, Aug. 4 at Lewiston’s Trinity Church.

In addition to teaching at Bates and making his own music, Boardman teaches strings full time in the Lewiston public schools and is the founder of, and a faculty member at, the Maine Fiddle Camp, in Montville. We talked with him about his return to vinyl, the simple power of a Hank Williams song, and the deeper meaning of scapegoating.

La frontière est morte is a thoughtful, even elegiac record. Does it speak to particular things that were happening in your life?

The songs all come out of very personal experiences and reactions to them, just processing. “One Soul at a Time,” which I recorded with the Gospelaires, was actually written way back in 2002 — a reaction to the 9/11 horror, and, you know, the “OK, what do we do with this?” kind of thing.

That’s the oldest song on there, but everything else is pretty up to date. Just where I’m at in my life, reacting to the world, coming to grips with the violent nature of human beings, and learning more and more about it. While I remain a glass-half-full kind of guy, and someone who clings to the promise of scriptural prophecy, the music also illuminates the state that we’re in as a species.

Greg Boardman performs “The Scapegoat (is innocent)”:

https://soundcloud.com/bowandstring/the-scapegoat-is-innocent

One of the instrumentals, and kind of an epic, is “The Scapegoat (is innocent).” Is that related to the so-called scapegoat mechanism, where social tensions are relieved by the creation and destruction of an innocent martyr — Christ being the obvious example?

I’ve been totally blown away by the writing of a French thinker named René Girard, who died a couple years ago. He talks about how, with scapegoating, we don’t even realize we’re doing it … and puts forth the idea that we have a chance to stop and think about, and understand, exactly what we’re doing in creating mobs and finding scapegoats, and finding solace in the elimination of the scapegoat.

It’s always nice to encounter a Hank Williams song.

The cover art for Greg Boardman’s new album was adapted from an installation by his sister, the late Deborah Boardman.

“Lost on the River” is a fairly obscure Hank Williams song, and I’ve always loved it — its simple words and melody. There’s just no defense, it’s right there. And it has to do with that general “lost-ness” that I feel and that’s happening in the world. At least the river is still moving, you know? And we’re floating on it. That’s where the hope is.

And the album art shows people in a boat.

That’s from an installation my sister did at the University of Indiana. [Deborah Boardman, who died in 2015, created The Flux of Matter, a multimedia installation exploring the cultures of Native Americans in Indiana.] She represents all these different ethnic groups in the boat, floating on the water at night, and it seems very thematic to me and reflected in the music.

Where does La frontière et morte in the album title come from?

It’s a phrase from the other cover version on the album, “Je viens d’écrire une letter,” by Gilles Vigneault. It’s basically a letter from a father to a son, a sendoff to the son. In the context of the song, “the frontier is dead” is an encouragement to the son to pay no mind, but to search out the fullness of being.

But there’s so much going on in the world today around borders, migrants, and refugees, and that’s one of the more interesting conversations going on. So in many ways the border is dead, but on the other hand, no, not yet.

Why a vinyl record?

One reason is the artwork. I felt very strongly about it because it’s my sister’s painting and it looks so much better on a vinyl LP cover than on a little CD.

Also, I’ve been enjoying the vinyl listening experience. To me, vinyl captures more of the room that the music was made in. And vinyl is conducive to a generally warmer sound than digital, which can sound very clinical.

When I listen to digitally recorded music, it’s like I’m listening to the production more than the music, if that makes any sense. Just the way it sounds and not what it is that’s sounding. But maybe that’s because I’m listening for what’s sounding anyway, as a musician who’s made a few recordings.