For a first-year Bates student, the leap from high school to college-level writing can be a daunting one.

You tackle new genres, you look at evidence more critically. And you learn that at Bates, good writing and good thinking are inseparable.

“Colleges are places where knowledge gets created,” says Daniel Sanford, director of Writing At Bates and the Academic Resource Commons (ARC), programs that provide resources for every stage of the writing process, in any discipline.

“When you learn to write and think in that setting, you are figuring out how to participate in the creation of knowledge.”

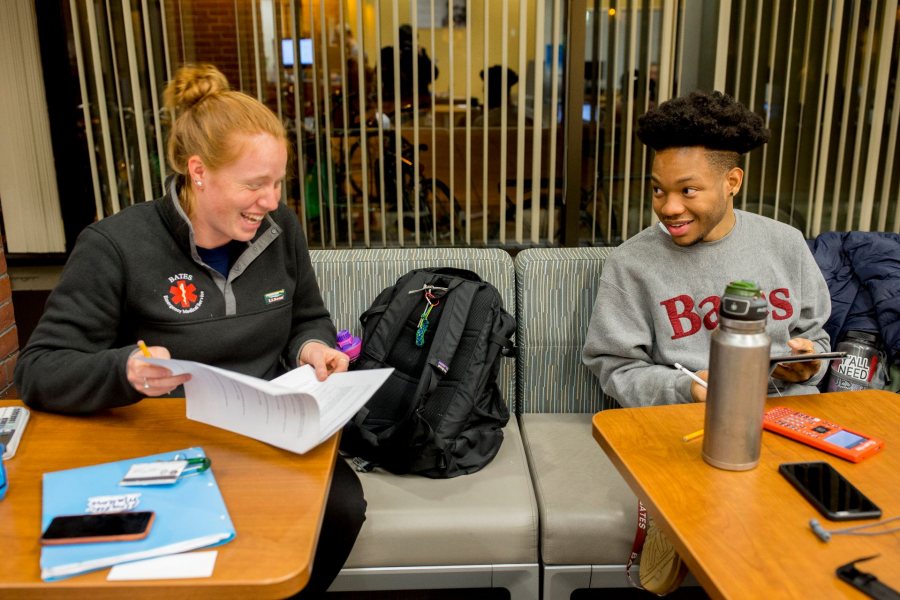

Claire Sickinger ’19 of Simsbury, Conn., a Peer Writing and Speaking Assistant for Assistant Professor of Asian Studies Nathan Faries’ “Defining Difference: How China and the United States Think about Racial Diversity,” discusses an essay for the class with Zhao Li ’21 of Guangzhou, China, in ARC. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

It can be a steep learning curve, but Bates’ newest writers are supported along the way. Most students take a First-Year Seminar, where professors teach writing alongside subject matter. They walk students through each step of the writing process and offer intensive feedback.

As the fall semester enters its second half, and students look to their final seminar papers, we’ve asked Bates professors and student tutors how new college writers can make their writing clear and compelling, and what common mistakes to avoid. Here is what they told us.

1. Before you start writing, know the assignment

One of the most avoidable mistakes Associate Professor of Politics Leslie Hill sees is not following directions. “Some students will write to the task they think they know, that may be familiar from high school — but the college professor may be asking for something different, in terms of content as well as the level of thinking.”

2. Know thy audience — and thyself

Don’t feel like you have to play the expert, says Professor of Religious Studies Cynthia Baker. “First-year college writers often seem to feel as though they need to present themselves as ‘experts’ in their essays instead of presenting themselves as well-informed and capable conversation partners,” she says.

Professor of Religious Studies Cynthia Baker teaches the First-Year Seminar “The Nature of Spirituality.” Here, in the 2015 iteration of the course, she shows her students a Rosh Hashanah tradition on Mount David. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

When students adopt the “expert” voice, Baker says, they sometimes feel that quoting heavily from sources means they’re not knowledgeable.

“It is far more often the case that professors are looking for students to demonstrate a firm grasp of the course materials and concepts by showing that they can synthesize ideas from a range of course readings and apply them to a particular problem,” she says. “This calls for positioning oneself in an essay as a well-informed conversation partner who thoughtfully and capably draws on a wide variety of others’ insights through extensive quotes and citations, rather than as a solo expert.”

3. Pay attention to genre

Biochemistry major Kenyata Venson ’18 of Memphis meets with Bridget Fullerton, assistant director of writing at Writing at Bates, to discuss her senior thesis on comparing synthesized drugs to herbal remedies for the treatment of glaucoma. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

“Technical writing is very different from expository writing in that there’s no fluff — readers just want what you did in the study,” says Technical Writing Assistant Ruth van Kampen ’19 of Brunswick. “That’s new to a lot of students.”

As a TWA, van Kampen helps biology students, often sophomores, with their writing.

4. Don’t lose the argument

Claudia Krasnow ’18 of Bedford, N.Y., works with Madelyn Heart ’18 of Winchester, Mass., on a paper for a Spanish class. Writing Tutors work among other student tutors in the Academic Resource Commons (ARC) in the Ladd Library. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

Writing Tutor Mariam Hayrapetyan ’19 of Valley Village, Calif. recommends this exercise: “Write out the prompt in your own words and when you write, make sure that each paragraph somehow contributes to the prompt.”

Take it to the sentence level, too. “Something that can improve clarity is ensuring that everything in each paragraph relates back to the topic sentence, and each topic sentence relates back to the thesis,” says Writing Tutor Kiyona Mizuno ’18 of San Francisco. “This will help keep the writing focused and organized. I find that outlining can be a useful strategy.”

5. Keep it simple

Zeke Smith ’19 of Weybridge, U.K., a Peer Writing and Speaking Assistant for Associate Professor of Russian Dennis Browne’s course on contemporary European film, works with Henri Emmet ’21 of New York. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

Don’t try to sound impressive, advises Mizuno. “A common trend I’ve noticed is sentences that are repetitive, are too long, or try to combine too many ideas. I would encourage students to try not to beat around the bush and to avoid forming long, complicated sentences to fulfill the word count — ideas can get jumbled and confusing fast if sentences get too wordy.”

Zeke Smith ’19 of Weybridge, U.K., who as a Peer Writing and Speaking Assistant helps First-Year Seminar students craft and correct their papers, often takes students through this revising exercise: “I have them reread their draft with a focus on which words can be cut out, and which sentences can be written more concisely. Sometimes finding the exact right adjective or verb can replace an entire description.”

6. Skip jargon

Chinese major Olivia Stockly ’18 of Cumberland Center, Maine, and biochemistry major Ken Hale ’19 of Cleveland, Ohio, prepare for a physics lab in the Academic Resource Commons. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

“It is very easy to use a lot of insider lingo, and writers should be conscious of this while they are trying to articulate their points,” says TWA Jackie Welch ’18 of Falmouth, Maine. “They should write as though the reader is familiar with their field but not necessarily with their particular discipline within that field.”

7. Cut the clichés

“Few people use ‘plethora’ right, and when they do, it’s a little precious,” if not downright pretentious, says Professor of French and Francophone Studies Kirk Read. “I would say we experience a plethora of plethoras in my world — that is to say, an excessive usage of this word!”

Adds Hill, “Nothing that comes after the phrase ‘throughout history’ is true.”

8. Revise, revise, revise

Associate Professor of Politics Leslie Hill speaks during a 2016 panel on the recent presidential election. This year, she is teaching a First-Year Seminar called “Race, Justice, and American Policy in the Twenty-First Century.” (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

“I have often advised students to use an after-the-fact outline or simply go through a draft and highlight their topic sentences,” Hill says. “That will tell you what exists on paper, and you can decide whether that is what you wanted to say or not.”

9. Don’t make the last least.

Bestselling author and syndicated columnist Amy Dickinson discusses her work and tells students how to tell their own stories during a session of “Family Stories,” Kirk Read’s First-Year Seminar, on Oct. 27. (Theophil Syslo/Bates College)

“Leave something for the end of your paper,” Read says. “Conclude without summarizing. Save something for the end, so that we appreciate what your point is and that you have proven it in some way.”

10. Record your paper, then listen to it

Reading a draft of a paper out loud can help you catch mistakes — and get around a fixation on grammar. “I try to tell students not to overworry about the grammar and mechanics of everything, but I am conflicted about that,” Read says. “I do want clean writers — so read your writing aloud. Record it and play it back to yourself to see if it makes any sense.”

11. Read!

Wenjing “Wen” Zheng ’21 of Wuhan, China gets her copy of “Strangers Tend to Tell Me Things” signed by the book’s author, Amy Dickinson, during a First-Year Seminar class on Oct. 27. (Theophil Syslo/Bates College).

“Read a lot of good writing — and read it as a writer,” says Cynthia Baker. “That is, think of yourself as a writer and study what the pros do. When you find course readings compelling, pay attention to how the writers make their content clear and compelling. What strategies do they use? How do they formulate their arguments and ideas? Give labels to those strategies, experiment with them yourself, and put them in your writer’s toolbox to pull out and use in your own writing.”

12. And write!

Paige Rabb ’20 of Stamford, Conn., takes notes during a meeting of her 2016 First-Year Seminar, “The Natural History of Maine’s Neighborhoods and Woods.” (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

“It might be helpful to think of writing in any form — journaling, noting, ruminating, fine-tuning —as a daily practice,” says Read. “Something that you turn to regularly and happily. Something that might even center you or help sort you out, like yoga, working out, meditation. For many successful writers, it’s a regular practice — and a joy.”