Until this week, Campus Construction Update had paid relatively little thought to the relatively large list of slang terms, many of them derogatory, that have “Dutch” in them.

That changed when we learned that the Peter J. Gomes Chapel has begun a new round of major restoration work and that Dutchmen will play an important role in it.

Naturally, we don’t actually mean human males of Dutch descent. Instead, in fields from carpentry to railroading to theatrical set-making — and in the case of the chapel, masonry — a “dutchman” is a repair made by cutting out a section of damaged material and replacing it with a matching section of new material.

All of which is to say that Bates has resumed work on a project, begun in 2011, to refurbish the 105-year-old chapel. During the 15 months of Phase One, the building’s entire slate roof was replaced, the copper cupolas on the corner towers repaired, and the masonry sheathing on the towers fully restored.

Then and now, water damage is driving the project. Penetrating moisture was degrading mortar joints, eroding masonry, freezing into giant icicles inside the towers, and damaging spaces used for chapel activities, notably the choir loft. (We witnessed the extraction of a time capsule from a tower wall during Phase One: It was full of water, and the original contents were “a slimy pile of goop,” says Pat Webber, director of the Muskie Archives.)

Crumbling cast stone trim around a window on the east side of the Gomes Chapel. (Doug Hubley/Bates College)

Begun this month, the second phase of the chapel restoration encompasses all the exterior masonry that wasn’t treated previously, plus the portico that protects the chapel’s entrance, all the building’s stained glass, and the concrete tracery embellishing the windows.

Exterior masonry repair commences just after Commencement 2019 and should be complete by November. In progress now, the Gomes stained glass and associated window tracery will take longer and be done in two batches. The windows in the chapel’s east and west walls (facing the Historic Quad and College Street, respectively) are being removed and should be reinstalled by this time next year. And the north and south windows will come out next fall and come home in September 2020.

Clear polycarbonate panes, resembling Plexiglas, will fill the window openings in the interim.

The Phoenix Studio team prepares to remove a set of stained glass windows in the Gomes Chapel on Nov. 30, 2018. (Doug Hubley/Bates College)

“The longer we wait to do the work, the worse the situation will get,” says Shelby Burgau, the Facility Services project manager directing the restoration. “The need is pretty obvious — it’s not preventative maintenance at this point, it’s work needed to keep the building intact and to prevent future damage.”

Further delay, she says, could elevate repair costs to a whole new order of magnitude. In particular, the college is concerned that water penetration at the rear of the chancel could damage the hand-painted reredos. “If we don’t address these issues now,” Burgau says, “the scope of work could just blow up.”

Consigli Construction, a familiar name to CCU readers, oversaw Phase One for Bates and has returned to see the project through.

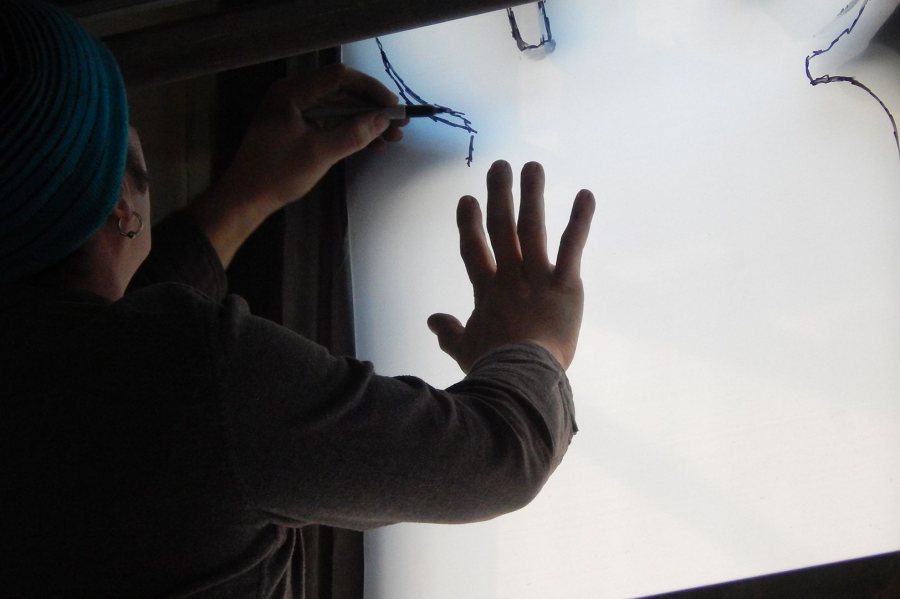

There’s no other way to say it: A Phoenix Studio employee traces around a section of window tracery as his team prepares to remove stained glass windows in the Gomes Chapel on Nov. 30, 2018. (Doug Hubley/Bates College)

The chapel will be out of service, for the most part, until 2021. Facility Services, the Events office, and the Multifaith Chaplaincy are harmonizing chapel bookings with the construction schedule.

Anyhoo, having sorted out “dutchman,” we next tackled “tracery.” This is cast concrete, also euphemistically known as cast stone, that makes a decorative pattern around a window or other opening. In the Gomes chapel, there’s tracery in the portico and around each stained-glass window.

During stained-glass installation, the panels are fitted into the so-called rabbet — a crevice in the tracery — and are secured with mortar and caulk. To remove the glass, therefore, all that gunk needs to be gouged out, a time-consuming chore.

The existing tracery will all be replaced. The original sections will be laser-scanned to produce virtual three-dimensional models, and these will serve as templates for the replacements.

The stained-glass depictions of Italian painter Fra Angelico, left, and the poet Dante Alighieri were restored in a Phoenix Studio pilot project a few years ago and will remain in place throughout the Gomes Chapel restoration. (Doug Hubley/Bates College)

A firm highly esteemed in Maine stained-glass circles, Phoenix Studio of Naples is restoring the windows. The Gomes stained glass includes depictions of 20 key figures in Western culture in the east and west walls of the nave; and, in the chancel, glass portraying Christ as the Lamb of God, flanked by Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John.

Phoenix submitted the winning bid on the Bates job about a decade ago. Circa 2012, Phoenix restored one five-window grouping on the west wall as a pilot project. That set, depicting the painter Fra Angelico and the poet Dante, will remain in place through the current work.

The restoration will entail the complete dismantling and documentation of the windows, cleaning of the glass and replacement of damaged pieces, and reassembling the whole works with new lead. (But no dutchmen: In stained glass repair, a dutchman is a lead strip used to hide a crack in the glass. Such repairs actually weaken the window and are no longer an acceptable practice.)

Cast stone window tracery in the portico of the Peter J. Gomes Chapel, photographed last June. All such tracery in the chapel will be scanned and replaced with exact duplicates. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

As for the portico, which Burgau says is “severely deteriorating,” Bates and Consigli have plans A and B. Plan A, she explains, “is to restore all the stonework, the tracery, the steps leading up, and the concrete slab it sits on. So, there’s already a decent amount of work associated with it.”

Hopefully there will be no call for Plan B: razing the portico and rebuilding it completely. “We are accounting for that, budget- and schedule-wise, and we’re hoping for the best. But it’s going to be one of the first pieces that Consigli tackles next year in case a full teardown is needed.”

BCO HQ: After our chapel visit, we headed back to the Bates Communications Office with the stained-glass Dante lingering in our mind’s eye. But midway through our journey, we found ourselves in a dark chamber, for we had lost the straightforward path.

Then we realized we had stumbled into a mechanical room in the basement of Lane Hall, and a quick retreat through a couple of doors returned us to the spotless corridors of BCO’s new home.

From left, editorial director Jay Burns, design director Grace Kendall, and strategic communications director Madge Hall meet in the Bates Communications Office nerve center. (Doug Hubley/Bates College)

The Communications team occupied its subterranean digs during the week before Thanksgiving. As previously reported, the offices were created from space most recently occupied by Residence Life, previously Post & Print, and, another generation ago, the Secretarial Pool. (Workers for project contractor Hebert Construction found some of their old bathing caps during the project.)

Designed by Canal 5 Studio, an architecture firm in the Portland, Maine, the conversion was a wholesale imagining of a space that extends underneath Alumni Walk and is laterally connected to Pettengill Hall by a tunnel, rumored to be a former fallout shelter.

“The outcome of the project is a really sophisticated area. I like it,” says Burgau, who oversaw the BCO construction prior to taking on the chapel. “We completed on schedule, on budget, and we got you guys moved in the day we were planning to.”

The move reunites BCO’s 17 members in a single building for the first time since 2002. (Three members, though, occupy executive offices one flight up from the rest of the team.) It’s a warren of workspaces made dazzling with white walls, bold accent colors (Bates garnet on the wall outside the CCU office), and brilliant LED lighting. The nerve center is a collaboration area lined with glass-walled offices, from which members of the team can view each other and wave in a friendly manner.

Surrounded by offices, the counter encourages collaboration among Bates Communications Office staff. (Doug Hubley/Bates College)

In terms of energy conservation, the BCO space is as good as it gets at Bates, says energy manager John Rasmussen. Along with the Campus Avenue dorms completed in 2016 and a few other facilities, “BCO is right where we want to bring all the rest of our facilities.”

The project encompassed the creation of a space-specific HVAC network whose variable refrigerant flow controllers save energy by closely matching the heating or cooling effort to the actual need.

More noticeable to the Bates communicators, though, is the lighting, which uses occupancy sensors — “occ sensors” to industry insiders like Campus Construction Update — to dim or extinguish lights when no one is around to benefit from them. The occ sensors also turn lights on when people enter a space, thus sparing precious muscle effort for banging keyboards.

Various technologies serve to detect occupancy, and the BCO system combines two: infrared detectors that respond to body heat, and sensors that respond to disruptions in an ultrasonic field.

Rasmussen reckons that occupancy-sensing lights, on average, use about two-thirds the electricity of traditional systems. Then you can factor in the savings realized through LED lights — which, Rasmussen estimates, draw about a third as much power as equivalent incandescents (remember those?) and about half as much as compact fluorescents.

Can we talk? Please use the digital communications apparatus below or send your questions, comments and favorite quotes from Dante, either Alighieri or Silvio, to Doug Hubley. If emailing, please put “Construction Update” or “I want my bathing cap back” in the subject line.