For someone who teaches film and screen studies, there aren’t always ready opportunities to bring students to the birthplace of one of the world’s greatest directors.

But there’s a great opportunity in Maine, and that’s the house in Cape Elizabeth where John Ford — creator of film classics like Stagecoach, The Searchers, and The Grapes of Wrath — was born, to Irish immigrant parents.

And that’s not the only Ford-related site in Maine that Jon Cavallero and his students visited when Cavallero last taught “The Cinema of John Ford,” in 2015: In Portland, there’s Ford’s longtime summer home on Peaks Island, the church he attended, neighborhoods of his youth like Munjoy Hill and Gorham’s Corner, and even a statue honoring the director in that last location.

Ford’s Maine origins are a point of pride for the state, and Cavallero has a hand in the latest celebration of the director. The statewide John Ford | 125 Years festival comes to Bates on Feb. 5 with a 7 p.m. screening of the 1940 Oscar-winner The Grapes of Wrath, based on John Steinbeck’s novel.

Cavallero presents the film on behalf of the rhetoric, film, and screen studies department, and will moderate a panel following the screening.

A location still from “The Grapes of Wrath,” 1940. (Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2009632217/)

“When you look at the pantheon of directors in the history of global cinema — not just Martin Scorsese and other Hollywood directors but directors like Akira Kurosawa in Japan or Abbas Kiarostami in Iran — they all list Ford as one of their influences,” Cavallero says.

Available for rental or from various streaming services, The Grapes of Wrath follows Tom Joad (Henry Fonda) as he returns to his family farm after four years in prison, only to find that the Joads are fleeing dustbowl Oklahoma and joining the desperate ranks of impoverished “Okies” heading for California.

Speaking to Maine Public Radio’s Maine Calling on Jan. 29, Cavallero explained that as Ford read Steinbeck’s novel and prepared for the film, he felt a connection to Tom Joad, particularly Joad’s goodbye scene where he tells his mother, “I’ll be everywhere — wherever you look.”

“That was the one that really connected with him,” said Cavallero. “It made him imagine his Irish parents and what it must have been like for them to leave Ireland and come to the U.S. back in the 19th century — it meant that it was a goodbye, possibly forever.”

We spoke to Cavallero about John Ford a few hours after the professor’s Maine Calling appearance.

What makes The Grapes of Wrath relevant today?

Jane Darwell as Ma Joad. (Courtesy of 20th Century Fox)

One way to talk about Grapes is to say “This is a movie about the Okies and their migration to California during the Dust Bowl and the Depression.” And that’s all true.

But another way to frame it — and this is what we’re hoping to do with the discussion afterward on Tuesday — is to say, “These are people that are forced to migrate because of a man-made environmental disaster. And in the course of their migration they face all kinds of prejudice and significant issues of income inequality. These forces put pressure on the family and ultimately fracture it” — and all these things are relevant today.

How does the film represent Ford at his best?

I’m not here to say Steinbeck wasn’t an artist or a talented writer. He obviously was. But I think Ford adds something to the story that is not in the novel: He adds the visual.

There’s one scene where Ma Joad is getting ready to leave and she’s going through her possessions, and she holds up these earrings, and she’s looking at a mirror. As she looks at herself in the mirror she smiles, and then the smile fades away and she lets the earrings down. And there’s no dialogue — it’s completely a partnership between the viewer and what they’re seeing on the screen.

We’re writing her story for her. And it’s an amazing little piece. It’s very subtle and, like a lot of Ford, so visual.

What does it mean to teach about Ford in his native state?

From left, Dorris Bowdon, Jane Darwell and Henry Fonda are shown in a scene from John Ford’s “The Grapes of Wrath” (1940). (Courtesy of 20th Century Fox)

His connection to Maine is important to me. It’s not often that you can teach a class where you can actually take students to the house where someone like Ford was born, or to his statue, or to the places that helped to form him and his perspective.

When we did the Ford course, the students made eight-minute video documentaries about different aspects of his life and work, and they presented them at the Maine Irish Heritage Center in Portland [formerly St. Dominic’s Church, serving the largest Irish Catholic parish north of Boston].

The space where the students presented is the space where Ford was baptized and where he served as an altar boy. So they’re standing in the same place where Ford learned about his Catholic faith, and it was incredibly powerful.

The other panelists at the Feb. 5 screening at Bates are Rachel Desgrosseilliers, director of Lewiston’s Museum L-A; Fowsia Musse, executive director of Maine Community Integration (formerly African Immigrant Association); and Marcelle Medford, Mellon Diversity and Faculty Renewal Postdoctoral Fellow and lecturer in sociology at Bates.

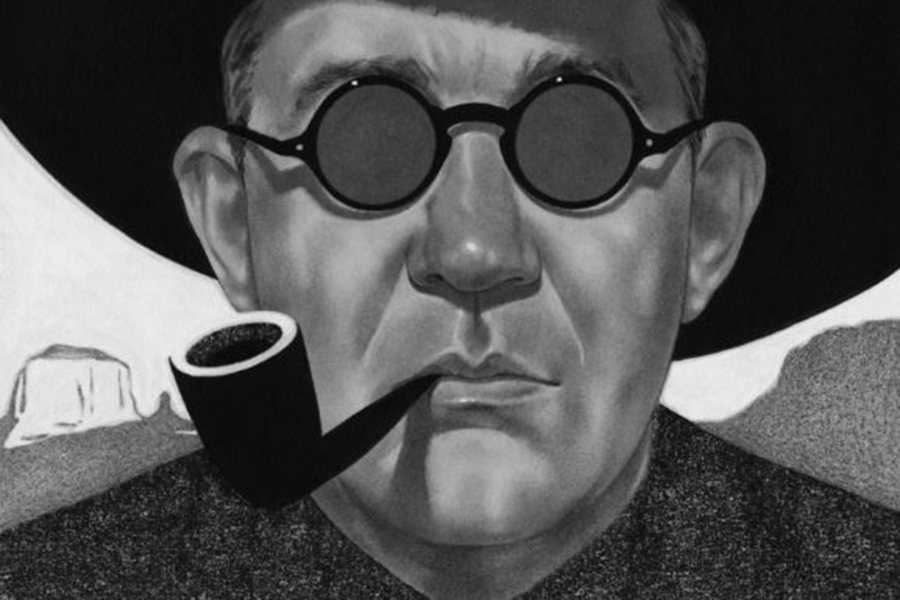

A portrait of John Ford by Edward Kinsella (detail).