Drawing a big and energetic crowd to a small Pettengill classroom, two majors in Chinese studies took the occasion of the 2019 Mount David Summit to share senior thesis research into China’s uneasy adoption of two pop-culture prime movers: video games and hip-hop music.

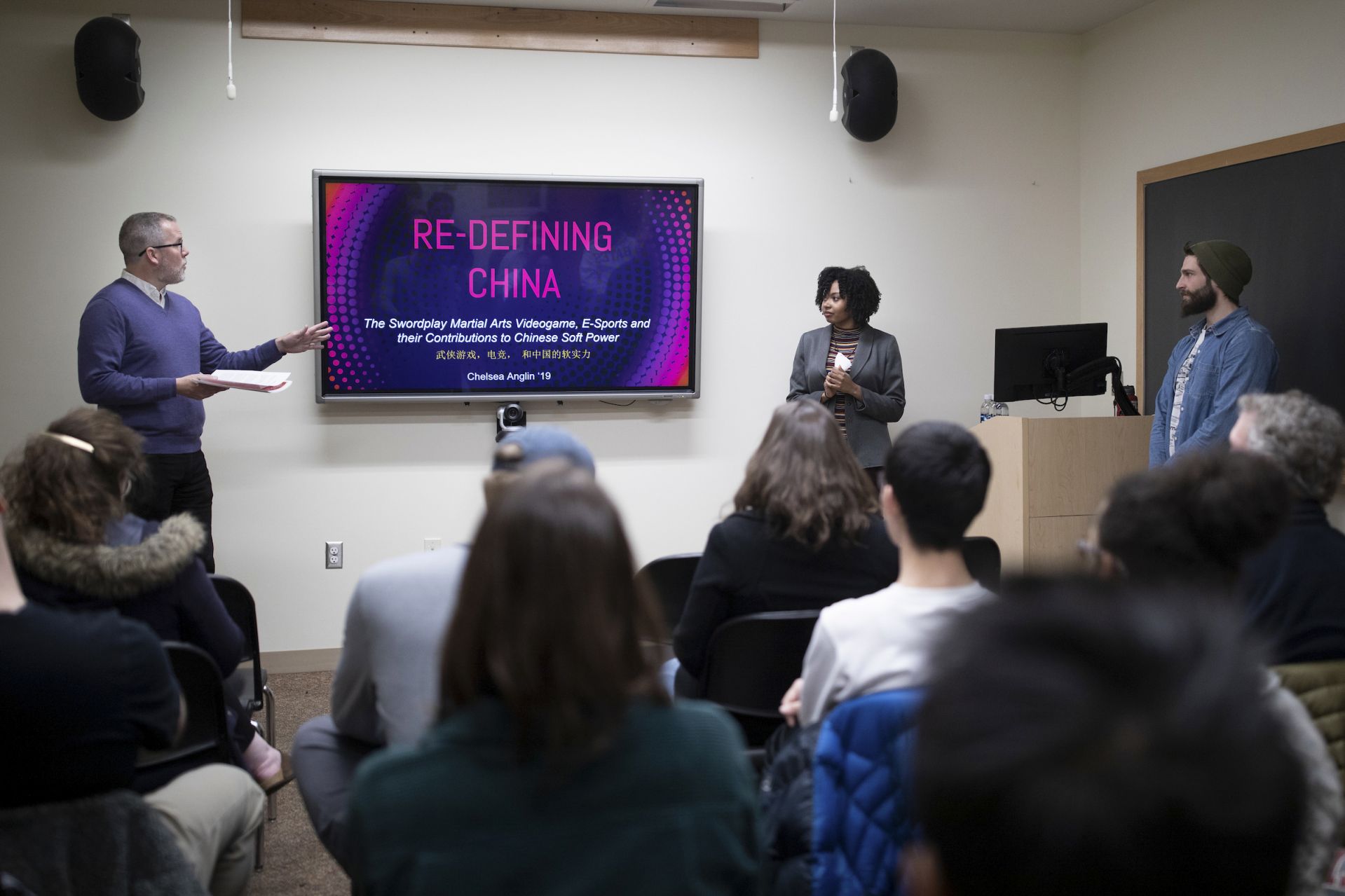

From left, Nathan Faries, assistant professor of Asian studies, introduces Mount David Summit presenters Chelsea Anglin ’19 and George Fiske ’19. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

Chelsea Anglin of Dayton, N.J., looked at video games and esports — competitive video gaming — in China and how they relate to that nation’s image among its Asian peers. George Fiske of West Hartford, Conn., examined hip-hop in China, focusing on a Voice-style reality show and two of its winners.

Though domestically oriented and, because of language and other factors, quite inaccessible to Westerners, China’s video game industry was the world’s largest in 2017, with 583 million participants. But, as Anglin explained, China arrived late to the party. Its first rudimentary games appeared only in the 1990s and various government interventions, including a 15-year ban on console games that ended in 2015, interrupted industry progress.

“I grounded my Chinese studies in something I’m passionate about,” Anglin said. A dedicated gamer herself, she spent many hours of her year abroad in internet cafes exploring the genre called wuxia (woo-shia) — “martial heroes.”

Senior Chinese studies major Chelsea Anglin presents research on video gaming in China during the 2019 Mount David Summit. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

A historically based genre widespread in opera, literature, and movies as well as games, wuxia depicts an ancient era in China populated with honorable, chivalrous men and women who wield swords in the defense of what’s good and right. (A clip of game play that Anglin showed also demonstrated how the games can mirror Chinese culture more broadly, as the “weapons” included acupuncture needles and a stringed musical instrument.)

If what Anglin called the “ancient Chinese feeling” of wuxia can exist happily embedded in game technology, the booming field of esports generates sharp tensions between moral and financial interests in China.

A lucrative industry based on multi-player gaming, “it’s very much something the Chinese government is trying to capitalize on,” Anglin said, and courses in esports are offered at the high school and college levels. Esports, she argued, “create a positive correlation between the Chinese and video game prowess,” an emerging cultural characteristic analogous to the pairings of Japan and animé art or Korea and K-Pop music.

But despite that prestige and the economic benefits of video gaming, Anglin pointed out, Chinese perspectives on the games remain in conflict. In China as elsewhere, they are seen as a distraction from studies and other more “wholesome” activities. Some compare the games to “spiritual opium,” a deeply pejorative label given opium’s role in the British exploitation of China.

An image from the character-design function of the game Jian Wang San.

Both personal gaming and esports, Anglin concluded, have the potential to extend China’s “soft power,” its cultural and social influence. She’s convinced, she said, that the wuxia aesthetic has the potential to “disrupt the current medieval European trope” that exists in today’s open-world video games, “if they can localize it well.”

Anglin’s presentation was rooted in a Bates-funded summer research grant that took her to Japan for research into pop culture and especially video games, a focus that she expanded while spending junior year in China. Her adviser was China specialist Nathan Faries, assistant professor of Asian studies, who also hosted the summit session.

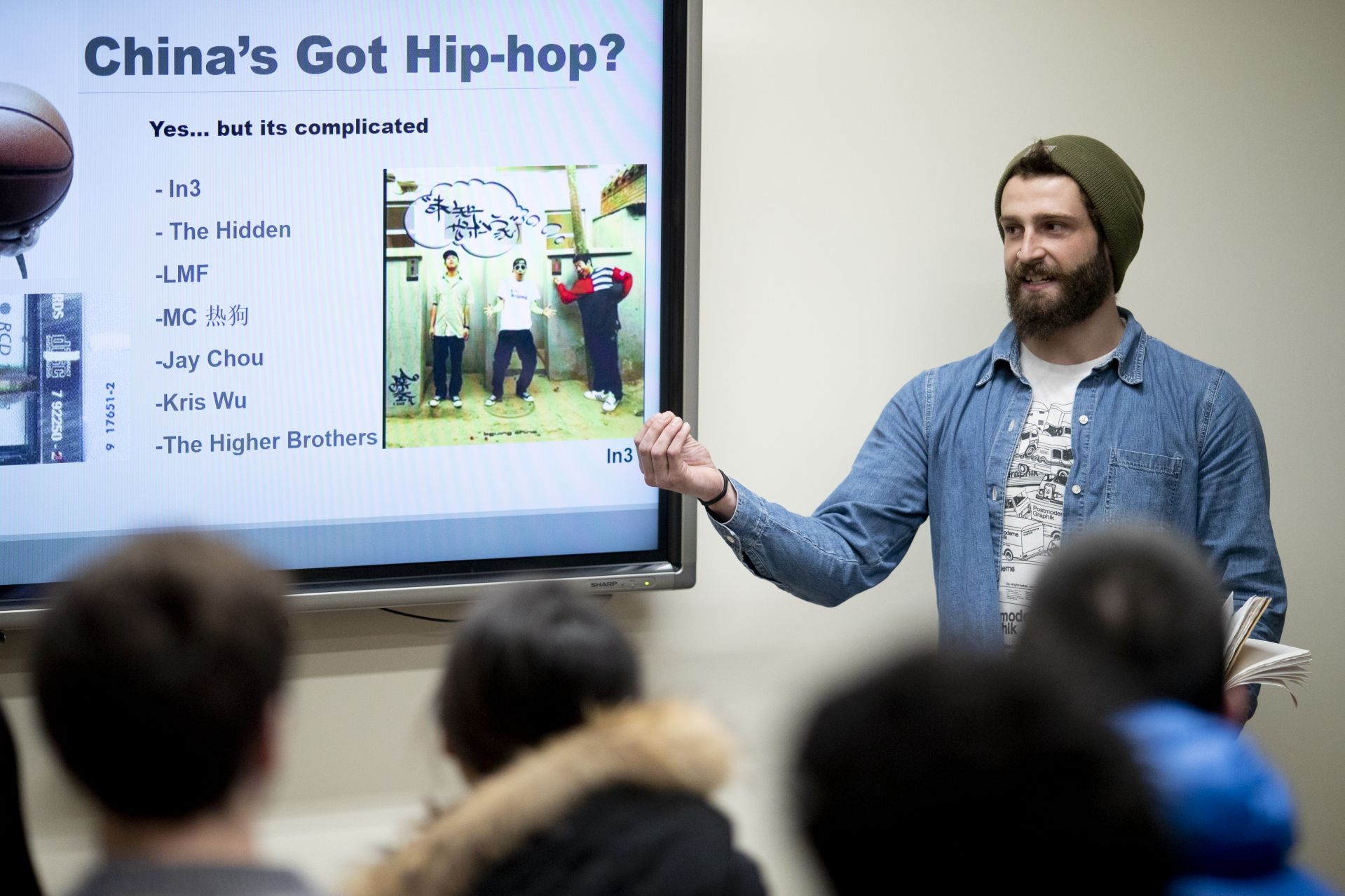

Fiske traced the growth of hip-hop in China from its introduction through so-called saw-gash CDs, discs remaindered out of Western markets and sold underground in China. Today, he explained, hip-hop is thriving but polarized: On the one hand, artists like Jay Chou represent a safe, mainstream approach to the music. “He integrates just enough Western style to make the music unique and interesting on the Chinese market, without really challenging or threatening any social taboo.”

George Fiske offers a look into the world of hip-hop music in China. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

On the other hand, there’s a much more feisty, vernacular, and authentic hip-hop scene that until 2017 was exclusively an underground phenomenon. And what happened that year to bring hip-hop into daylight was the debut of The Rap of China, a thoroughly commercial television competition credited with establishing hip-hop as a mainstream force in mainland China.

“I’m here today to argue that this wasn’t selling out on the part of the rappers, and it wasn’t just exploitation on the part of advertisers,” Fiske said. Despite the heavy doses of vitamin-water advertising, the show nevertheless represented “an alternative pathway into mainstream venues” for rap — a breakthrough Fiske later described as “monumental.”

The show found a way to guard both the underground rappers’ own aesthetic and the moral concerns of government and society, Fiske explained. That way was solidarity: As long as everyone on stage respected both hip-hop culture and prevailing Chinese culture, they were all one big happy family.

Fiske used the co-winners of the first season of The Rap of China, GAI and PG One, to show what happened to Chinese hip-hop in the wake of the show’s tremendous success. Among the underground vanguard when they arrived on the show, both artists challenged traditional taboos and norms with their music, style, and image.

Proud of his local dialect and adopting a roaming gangster-cum-ascetic monk persona — “a poetic bandit, almost,” Fiske said — GAI used traditional poetic and historic archetypes to tweak the assumed hegemony of “Chinese-ness.” Meanwhile, PG One’s provocative, nimble, and dynamic music was rooted in an unparalleled expressive command of the Chinese language.

All told, Fiske’s presentation amounted to action, reaction, and ultimately a synthesis emerging from the two. Winning 1.3 billion online views in the summer of 2017, The Rap of China was “a rocket ship aimed at the heart of Chinese popular consciousness.“

Presentations of senior thesis research into pop culture in China filled a Pettengill Hall classroom. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

It put rap on the map — but it may have been too much too soon for the powers that be, especially given a scandal, involving PG One lyrics about cocaine use, that emerged in the wake of the series’ first season.

In January 2018, the Chinese government “banned” hip-hop — an action that was actually more a “filtration” of the more egregious performers and not outright suppression. “China doesn’t necessarily have any problems with hip-hop style of music, so long as it promotes the right values,” Fiske explained.

“This is very much indicative of the obstacles that hip-hop has faced in the past [in China] and will continue to face in the future,” he concluded, noting that PG One has dropped out of sight, while GAI is still in the game but has become much more mainstream.

And the rocket ship is now more of a Roman candle: Renamed China’s New Rap, Fiske said, the show returned in 2018 with the stated mission of promoting “positive energy and socialist values.”

Fiske’s thesis adviser was Professor of Chinese Yang Shuhui.