A century ago, Bates took possession of 11,000 acres of Maine timberland, thus beginning the 17-year saga of the Bates Forest, a story of noble ambitions that ultimately couldn’t withstand the triple whammy of bad luck, high taxes, and the Great Depression.

The land had come to the college from Benjamin Clark Jordan, a successful lumberman with extensive ties to Bates. He had died in 1912, and his will invited Bates to take over about 18 square miles of land in several parcels in and around the southwest Maine town of Alfred, about 60 miles from campus.

Circa 1932, white pine logs from the Bates Forest await processing at a mill pond in Alfred, Maine. (Muskie Archives and Special Collections Library)

Jordan’s bequest had a few stipulations. The big one required that Bates create a new academic department in forestry, to be funded by income from lumbering, an industry that was enjoying good times thanks to the economic boom created by U.S. spending during World War I.

Bates readily agreed; then, as now, colleges look for ways to stand out from the crowd, and The Bates Student noted that the new major, a four-year “professional” course of study, would make Bates the only college in New England offering a bachelor of science degree in forestry.

Besides, adding a new academic program made sense in those heady times for the college.

For one, Bates was blossoming under President George Colby Chase. During his 25-year presidency, Bates had added a dozen buildings, and the faculty had grown from nine to 38 and the student body from 167 to 500. The Bates name would soon spread around the globe thanks to international debate.

The offices of the Bates Forest in Alfred, Maine, circa 1932. (Muskie Archives and Special Collections Library)

Plus, the donor, Benjamin Jordan, was a revered member of the Bates community. A Freewill Baptist, longtime Bates trustee, and temperance worker, he was one of Maine’s “most prominent and useful citizens,” in the words of Alfred Anthony, author of Bates College and Its Background.

Jordan’s two daughters, Nellie Belle and Dora, had both graduated from Bates. A brother, Lyman, was an 1870 Bates graduate who, by the early 1900s, achieved legendary status as a chemistry professor nicknamed “Foxy.”

The original terms of Jordan’s will gave daughter Nellie Jordan control of the forest land and income from lumbering operations until her death. Then, Bates would take over. But in 1917 she offered the land to Bates in return for a lifetime annuity of $3,500 per year, plus another $500 annually for her sister. Bates accepted the offer on Dec. 21, 1917.

But troubles were growing in the Bates Forest.

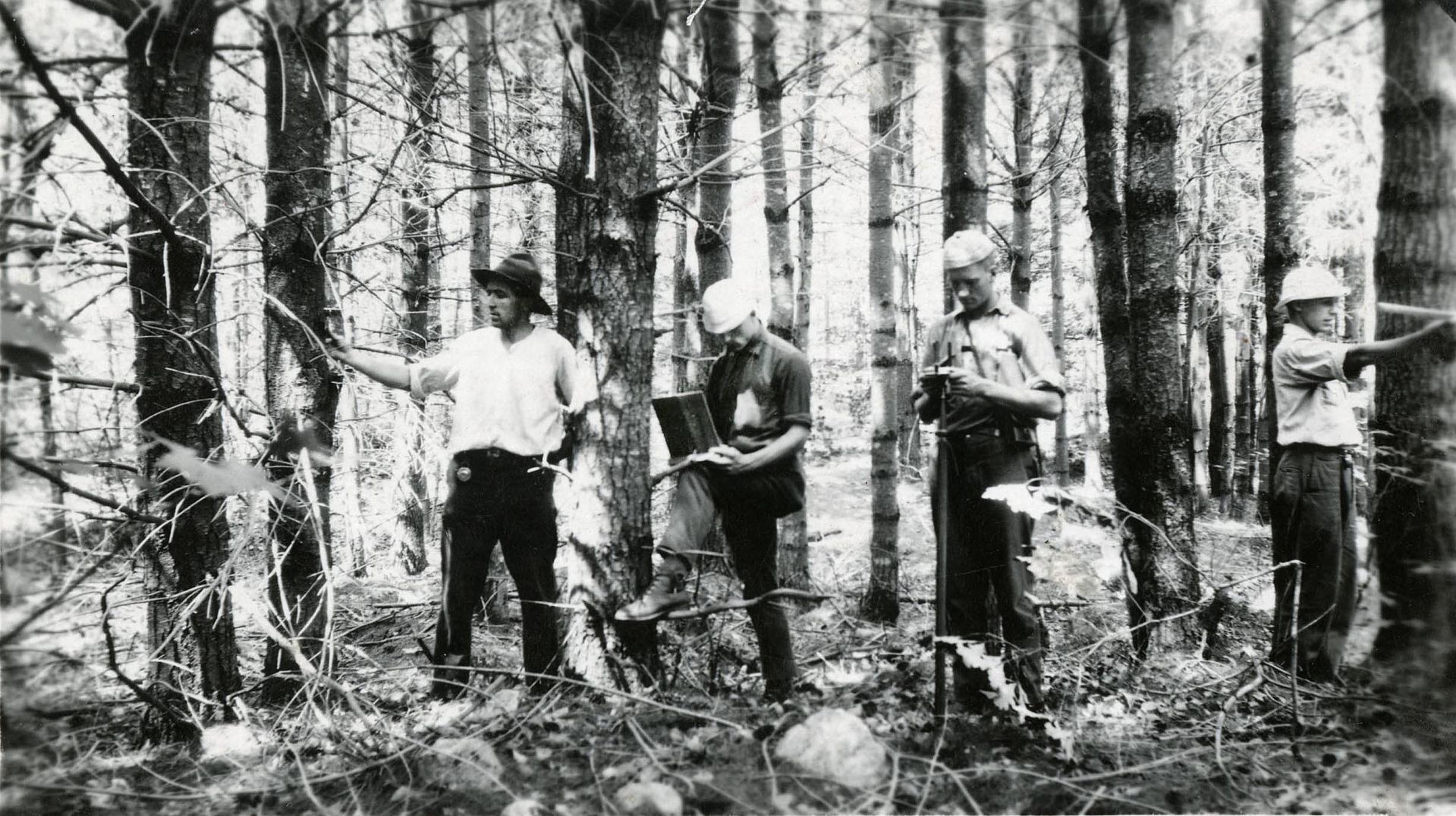

By 1921 the forestry program was well underway. That summer, four aspiring forestry majors did their required summer work at the Bates Forest under Assistant Professor of Forestry Bernard Leete. They learned about scaling logs at the Jordan mill in Alfred; estimating the volume of lumber on an acre; compass surveying and blazing woodlot boundaries; and studying rate of growth by stump measurements.

In 1921, Assistant Professor of Forestry Bernard Leete, left, led aspiring Bates forestry majors during summer fieldwork in the Bates Forest. (Muskie Archies and Special Collections Library)

There was fun, too, including fishing at Bunganut Pond, the site of their camp. “The swimming was particularly enjoyable during the very hot month of July,” write Leete in the October-November 1921 issue of The Bates Alumnus.

But troubles were growing in the Bates Forest.

Though the 1920s are remembered as “Roaring,” that famous economic boom took place only after a severe depression in 1920 and 1921, one that came down hard on the Maine lumber industry and the college’s investment in its lumbering business.

Around this time, Leete, no doubt influenced by his fieldwork at the forest, urged Bates to take a more active role in the business. Bates agreed, hiring an experienced forester, Raymond Rendall, to join Leete in a “cruise” of the property in late 1921 to measure trees and collect other data.

An unidentified worker tends to seedlings at the Bates Forest in this undated photograph. (Muskie Archives and Special Collections Library)

Rendall was a graduate of the University of Maine and the Yale School of Forestry. Described as a “two-fisted, square-jawed” veteran of World War I, he’d gotten forestry experience of a different kind in the Great War. Part of an engineering company running a sawmill to create trench timbers and railroad ties, Rendall left his company to fight at the front, including the epic Battle of the Argonne Forest.

The results of Rendall and Leete’s 1921 cruise were sobering. The land was “understocked,” Rendall noted, with only a quarter of it supporting “merchantable stands of timber.” The rest had been “excessively cut over or was nonproductive.” There are hints that the land had been over-lumbered from the time of Jordan’s death in 1912 to when Bates took over in late 1917.

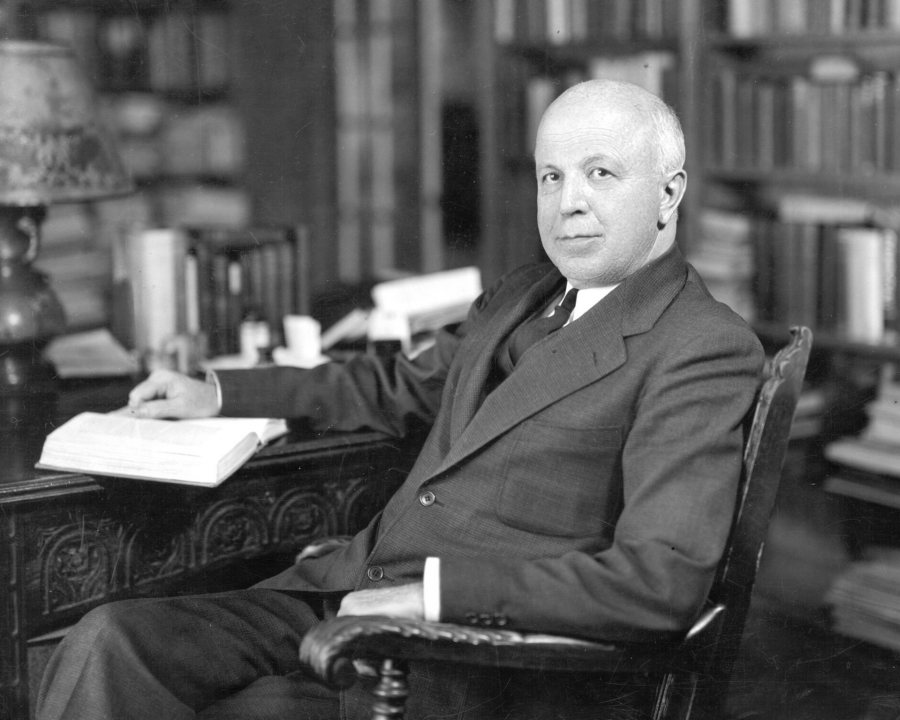

President Clifton Daggett Gray, who succeeded Chase in March 1920, sounded the alarm in his 1921–22 annual report. “Instead of having sufficient income…to pay taxes, annuities, and the expenses of management as well as a modest department of forestry at Lewiston, we find ourselves facing an annual deficit for the next 10 years of approximately $10,000,” he wrote. Today, such a loss would be a hit of several millions dollars annually.

Raymond Rendall was the “two-fisted, square-jawed” forester whose work nearly saved the Bates Forest. (Muskie Archives and Special Collections Library)

With the news, the college pivoted quickly. Leete was let go, and Bates vastly downsized the academic program. Gone was the four-year program — Bates would never graduate a forestry major — replaced by a general forestry course in the geology department.

Meanwhile, efforts at the Bates Forest turned toward restoring the timberland and creating Maine’s first demonstration forest to display for the public, woodlot owners, and Maine forestry officials the value of “scientific management” and “the feasibility of conservation and applied forestry,” said Gray. Lumbering would continue, but only under Rendall’s careful watch.

Still, it would be a race against time.

Gray was hopeful. “The careful and exact management of Mr. Rendall has resulted in a much happier outcome than was anticipated in the survey two years ago,” wrote Gray in his 1924 report.

Still, it would be a race against time. “While it is true that after 20 years we shall begin to see a much larger income from these forests, it will be necessary during this long interval to administrate this trust with the utmost economy,” Gray wrote.

Rendall established a nursery at the Bates Forest, annually planting upward of 39,000 white pines and selling thousands of others to raise funds. He thinned overcrowded stands and pruned trees to improve growth. A second cruise in 1927 showed that the amount of land with marketable timber had increased to 30 percent.

More good news followed as the Maine legislature gave timberland owners tax relief by allowing them to list lands as “auxiliary state forests,” thus paying yearly tax on the land (not the growing trees) and paying tax on timber only when harvested. By 1928, Gray noted in his annual report that “there is at least a little light.”

A thinned stand of white pine at the Bates Forest circa 1932. (Muskie Archives and Special Collections Library

But then came the whammies. In April 1930, fire swept through 460 acres of the forest; Rendall estimated that $5,000 worth of timber was destroyed. Fire doesn’t just destroy timber, he wrote in the May 1932 issue of The Bates Alumnus. “It kills reproduction of all ages and lays the land to waste…for years and years.”

Gray struck a sober note in his 1930 annual report, wondering if “the owners of any other forest can win out in the race between fire and taxes on one hand and natural growth on the other.”

But it was the Great Depression that would do in the Bates Forest. Lumber prices and demand slumped, and cheaper wood products from the West Coast made inroads in the East. “The Bates Forest, like all business enterprises during this period of depression, is hard hit by the inert lumber market,” wrote Rendall in 1932.

Meanwhile, taxes jumped yet again, and Maine towns refused to acknowledge the new auxiliary forest law. “It became apparent to the trustees of Bates College..that the undertaking was hopeless,” The Bates Alumnus reported.

In his annual reports, President Clifton Daggett Gray often wrote about the challenges of managing the Bates Forest. (Muskie Archives and Special Collections Library)

After 17 years of trying mightily to make the Bates Forest work for Bates and for the donor, the college asked the Maine Supreme Court to relieve Bates of its ownership, and in January 1934 the court agreed. The land was sold — most to the federal government — with Nellie Jordan receiving funds to continue her annuity. The court appointed Rendall as receiver; he would go on to become Maine’s forest commissioner.

Today, about 3,600 acres of the original Bates forest remains public land, operated as the Massabesic Experimental Forest by the Northern Research Station of the Forest Service. The rest is owned privately.

While Bates never graduated a forestry major, one could say that the program did have a profound, if indirect, influence on the college. In 1922, a would-be forestry major, Norman Ross, graduated from Bates with a double major in physics and math. He rejoined the college as assistant bursar and, 44 years later, retired as treasurer.

More than anyone, Ross helped Bates maximize its financial resources in the middle part of the 20th century, during periods of both expansion and caution. Under Ross, Bates developed a famously savvy and careful mindset that continues to this day. (Ross once drove to Presque Isle for a military-surplus potato peeler, refrigerator, and dishwasher for the college kitchen.)

As his successor, Bernard Carpenter, once said about Ross, “He instilled upon me the absolute necessity of never making a commitment to spend a dollar unless you knew where it was coming from.” Because, after all, money doesn’t grow on trees.