“Follow the money,” the FBI source Deep Throat told the reporters unraveling the Watergate burglary in the film All the President’s Men.

A corollary for our time might be “name the evil.” If you want to understand what’s driving a particular conspiracy theory, advises rhetoric professor Stephanie Kelley-Romano, then try to characterize the perceived evil that motivates the theorists’ stories.

For instance, why did then–political aspirant Donald Trump boost the “birther” conspiracy, the lie that Barack Obama’s presidency was illegitimate because Obama hadn’t actually been born in the U.S.? What was the perceived evil behind that particular rhetoric?

“It’s pretty plain,” Kelley-Romano told a Bates audience on Sept. 19. “It’s fear of a black president, right? It’s just blatant white supremacy and racism. And so, when we see that for what it is, it becomes a lot easier to understand the subsequent rhetoric.”

Associate Professor of Rhetoric, Film, and Screen Studies Stephanie Kelley-Romano poses in her Pettigrew Hall Office. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

Kelley-Romano, associate professor and chair of rhetoric, film, and screen studies, was honored last winter with Bates’ Kroepsch Award for Excellence in Teaching. Giving her Kroepsch Lecture in Pettengill Hall last week, she treated a packed Keck Classroom to a quick tour of her ongoing conspiracy rhetoric research.

The talk, a sort of field guide to conspiracy rhetoric, was another in a welcome and timely series of Bates examinations of truth and untruths. In fact, earlier in the day and also under the Kroepsch aegis, four faculty members described how the concept of truth figured in their teaching, a topic suggested by Kelley-Romano.

During that event, in recounting how he and Alex Dauge-Roth designed their First Year Seminar scrutinizing the nature of truth, economist Michael Murray neatly summarized how the context has changed around the concept.

“The motivation was really our shared dismay and outrage at a climate in which alternative facts become something that people think of as real, and the dismissal of what one might learn through science,” Murray said. “We wanted somehow to provide students with a venue in which they could deal with that environment more richly and deeply.”

Malcolm Hill, vice president for academic affairs and dean of the faculty (right), talks with Charles Franklin Phillips Professor of Economics Michael Murray and Professor of Psychology Amy Douglass, presenters at the panel discussion “Truth and How One Teaches It,” a prelude to Stephanie Kelley-Romano’s Kroepsch lecture later in the day. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

Kelley-Romano’s late-afternoon lecture, distinguished by clarity, urgency, and humor, was another such venue. She focused on four subjects of her research: people who say they have been abducted by space aliens; the television blockbuster The X-Files; Trump’s conspiracy rhetoric; and the Fox News treatment of the Brett Kavanaugh confirmation hearings.

“A conspiracy is a group of people who are doing something in secret for harmful or evil reasons,” Kelley-Romano explained. “And so a conspiracy theory is the belief that there is a group of people who are doing something in secret for harmful or illicit reasons.

Further, she asked, “What are the defining characteristics of it? Thematically, what are the things that unite it? Formally, what are the common argumentative strategies?” And in the case of television’s X-Files and the Kavanaugh hearings, “what are the visual trappings?”

A characteristic of conspiracy rhetoric, and a recurring device in the show The X-Files, is the mixing of fact with fiction as a means of lending credibility to the latter, says Kroepsch Award honoree Stephanie Kelley-Romano. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

As a doctoral candidate at the University of Kansas in the mid-1990s, Kelley-Romano found rhetoric around human-alien encounters becoming something of a theme in her life. She was an obsessive fan of The X-Files, whose main characters, FBI agents Fox Mulder and Dana Scully, were bent on exposing a federal plot to conceal the earthly activities of extraterrestrials.

“I didn’t know if I wanted to be Mulder and Scully or if I wanted to date them, but I knew I wanted more of them,” Kelley-Romano told the Bates audience. “And so, since I was in graduate school, I had to write about it, because I couldn’t [otherwise] justify watching it.”

Meanwhile, defying her Ph.D. adviser (“You’ll never get a job,” he warned), Kelley-Romano interviewed 100 professed abductees to form the basis of her dissertation, on the rhetoric of alien abduction.

A characteristic of conspiracy rhetoric is the mixing of fact with fiction as a means of lending credibility to the latter. An X-Files motif was the use of actual or carefully replicated news footage, often with text superimposed on it that serves the fictional plot. (One episode references the famous Zapruder film of John F. Kennedy’s assassination in revealing that it was actually a key X-Files character, the Cigarette-Smoking Man, who killed the president.)

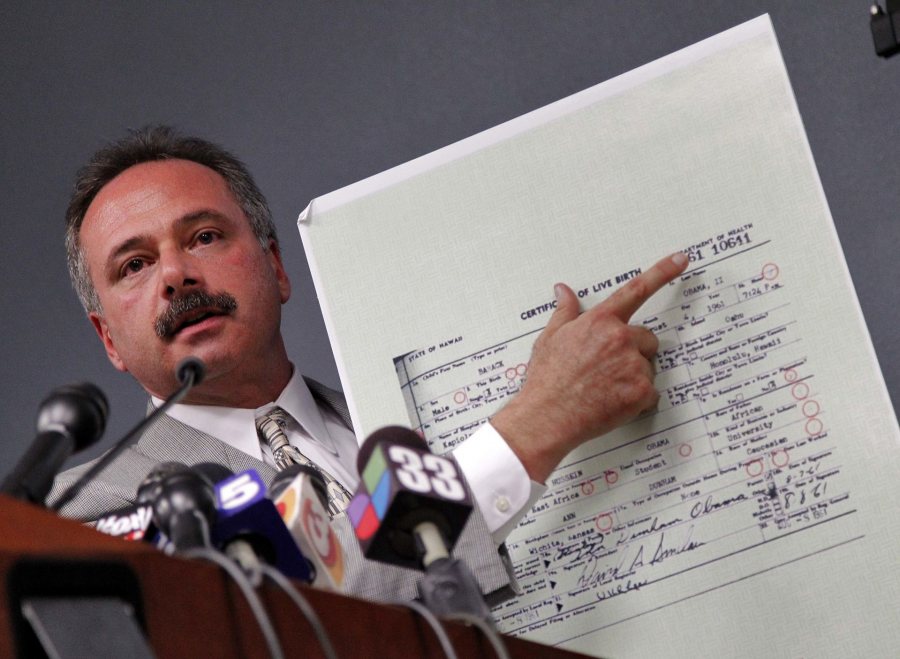

In 2012, Arizona conspiracy theorist Mike Zullo announces at a press conference that Obama’s birth certificate is a forgery. The birther conspiracy that dogged President Obama was fueled by “a fear of a black president,” explains Stephanie Kelley-Romano, associate professor of rhetoric, film, and screen studies. (AP Photo/Matt York)

Fact vs. fiction gets complicated in a hall-of-mirrors way. Kelley-Romano noted that some professed abductees believe that programs like The X-Files are actually part of a real federal disinformation campaign. If it’s just science fiction, the logic goes, who would believe it? So a drama about a government conspiracy to hide the truth about extraterrestrial activities is, in reality, itself part of such a conspiracy.

Some kind of perceived evil is an organizing principle or orbital center for a given conspiracy theory.

“The blurring, and the inability to make these distinctions, is part of the problem with the perpetuation and proliferation of conspiracy belief,” Kelley-Romano said.

Conspiracy theories exploit the human need for coherence in stories, something that communications theorist Walter Fisher called narrative fidelity. “We like it when things seem to hang together,” Kelley-Romano explained. Yet “narrative fidelity or narrative rationality and rational argument are not always in sync.”

Which brought us to the role of evil in conspiracy rhetoric, a concept Kelley-Romano attributed to Earl Creps of Northwest University. For Creps, some kind of perceived evil is an organizing principle or orbital center for a given conspiracy theory. In order to bust that theory, we need to identify the evil that the conspiracy believers are perceiving and responding to.

Kelley-Romano’s witty, energetic style captivated her listeners. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

“And how can we get at combating that, right? Because we all know that we are not going to argue…any type of new mindset [into] most conspiracy believers.”

Playing on the desire for narrative fidelity, The X-Files rendered as art another tactic near and dear to conspiracy theorists: the kind of associative “logic,” Kelley-Romano explained, “whereby things that come in concurrent succession are somehow argumentatively or rationally related, which is not necessarily the truth.”

She admitted, “That was part of why I loved watching the show. I loved the intellectual calisthenics and the illogic of it.”

But what’s fun and lovable over pizza on a Friday night becomes something different and much less fun when it’s a factor in mainstream political discourse, including conspiracy rhetoric à la Trump (whom she dubbed “the conspiracy president”), and Fox News coverage of the Kavanaugh confirmation hearings.

Borrowing a phrase from Wabash College’s Jeffrey Mehltretter Drury, Kelley-Romano held up Trump as a great example of the “rogue ethos”: the “notion that your credibility as a politician comes from the fact that you’re outside the system. You’re willing to shake things up. You’re willing to go rogue.”

However, as Drury made clear, the rogue has to profess populist solidarity. “You can’t do it for your own personal gain,” Kelley-Romano said. “It has to be for the people.”

President Trump is an example of the “rogue ethos” at work, says Associate Professor of Rhetoric, Film, and Screen Studies Stephanie Kelley-Romano. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

Trump positions himself as a latter-day Rick Blaine, the Casablanca protagonist who wants to stay out of the fray but finally has to step up and do the right thing. “I don’t want to talk about this,” Trump might say, “but when I walk down the street, they’re saying, ‘Don’t give up. Don’t give up.’

“And so he has to talk about it, right?”

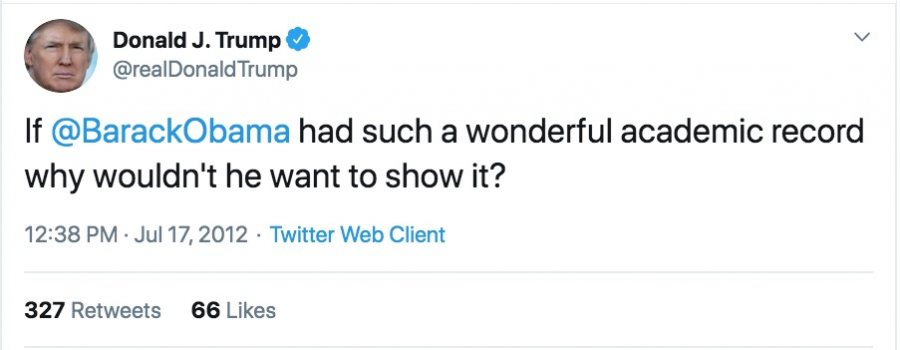

Trump is also a master of rhetorical questioning, which has the desired effect of spreading doubt and suspicion without leveling actual charges that would require evidence. “He’s just wondering. He’s just asking,” Kelley-Romano said. “And he manages to absolve himself of any type of responsibility.”

With a shout-out to advisee and collaborator Claire Sullivan ’19, whose senior thesis examined the role of conspiracy rhetoric in Fox News’ Kavanaugh coverage, Kelley-Romano used the 2018 hearings as an example of “tactical framing.” (The concept comes from Kathleen Hall Jamieson, a professor of communication and the director of the Annenberg Public Policy Center at the University of Pennsylvania.)

A Donald Trump tweet from Stephanie Kelley-Romano’s presentation shows the president’s skill with rhetorical questions.

That’s when news organizations turn their attention away from actual news content and instead, report “on the coverage or the positioning of something,” she explained.

“So rather than focus on what was actually being said during the testimony, there was this meta-narrative that unified the Fox News coverage — which was, this is actually a conspiracy by the Democrats to thwart the nomination of Brett Kavanaugh, and, in particular, out of revenge for the Clintons.”

She added, “When we think about that problem of rhetorical evil, what is this conspiracy responding to? I would argue, that this conspiracy is hell-bent on defending a particular way of American life — of privilege and white, heteronormative men. And specifically, Brett Kavanaugh.”