Last summer, exactly 30 years after I graduated from Bates, my favorite professor retired, which led me to think about my early experiences with interdisciplinary thinking and international awareness — and how these tools prepared me for work and life.

To prepare for Steve Kemper’s retirement party, I dug through a box of college notebooks and papers that I had moved unopened from one apartment and city to the next for the past three decades.

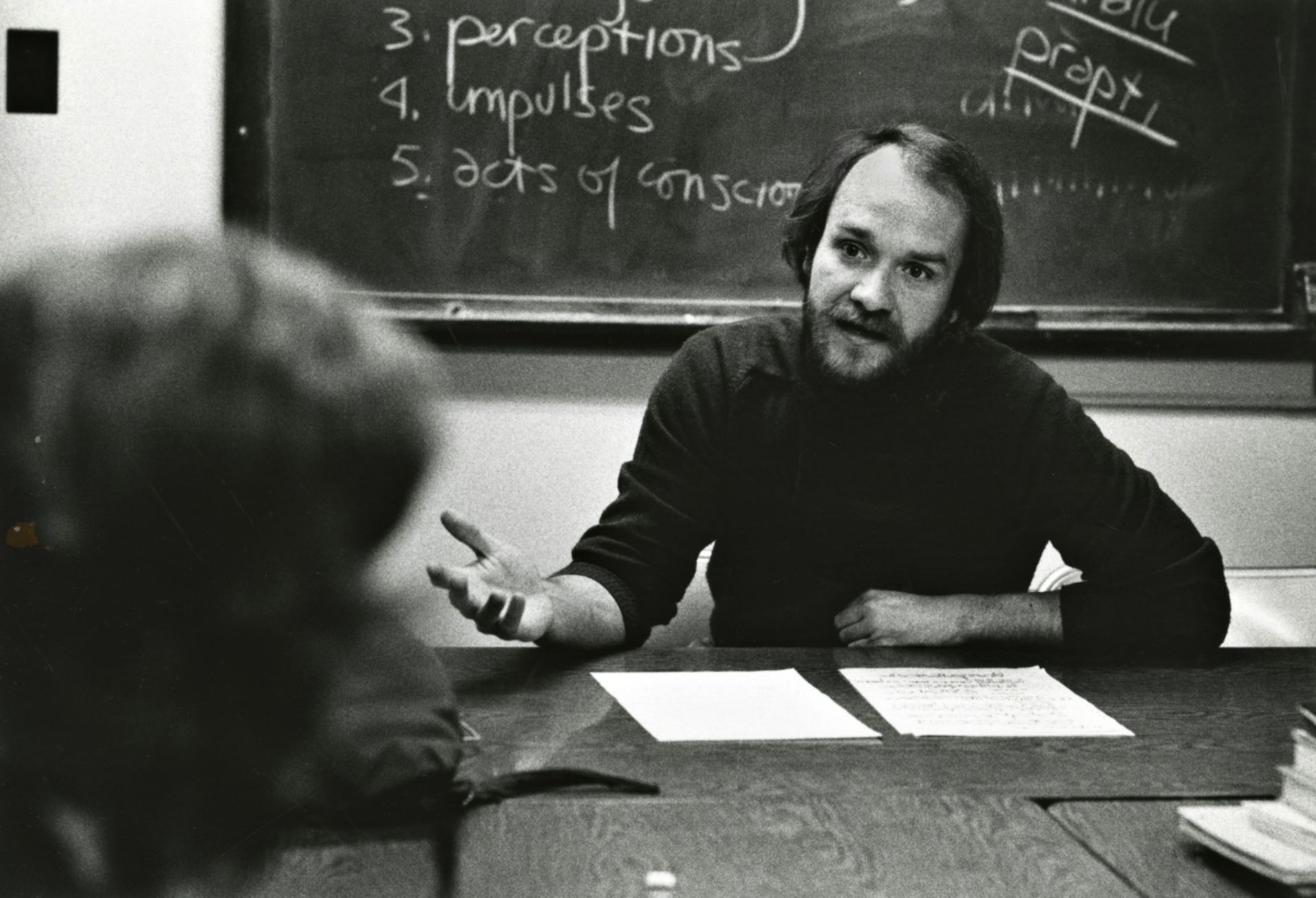

Seen circa 1981, Steven Kemper joined the Bates faculty in 1973 and retired in 2019 as professor emeritus of anthropology. (Muskie Archives and Special Collections Library)

I found a pastel-pink exam book, with my name in pencil on the cover. Inside, I saw my handwriting, no different from today’s.

As I began to read, I didn’t remember writing or knowing any of what was on these pages. My 19-year-old self possessed deep specific knowledge that is long gone from my memory, 30 years on. But I did recognize that this exam was for an anthropology course Steve taught my sophomore year, on culture and politics in South Asia.

Steve’s name doesn’t show up anywhere, but his handwriting is unmistakable. A cursive like no other: loopy, ornate, enthusiastic, and generous, with tails on letters like x, p, and y flowing down with a flourish. Steve had written comments in the margins, including a correction when I wrote “bride price” instead of “dowry.”

I learned from my exam that back when I was only 19, I knew a lot about what might be considered pretty esoteric things. Before this class, I knew nothing about South Asia. I enrolled by accident, thinking “South Asia” referred to what I now know is Southeast Asia. My father is a Vietnam War vet, and I wanted to learn more about Vietnam.

Instead, on the first day of class, Steve had pulled down a map from a roller above the chalkboard and drew me quickly into learning about India and its neighboring countries — including Sri Lanka, where I eventually spent many years and learned two of the languages spoken there.

Back then, I was focused on the details of the societies Steve instructed us about. I am sure I didn’t appreciate what was at stake, why this kind of learning matters so much.

Memories can be triggered by a whiff of an odor, a snippet of a song, or a taste of food: events, experiences, and emotions long ago tucked away spring up at a resonant prompt. Holding the exam book in my hand, I suddenly remembered working in the college library; studying for hours for Steve’s tests; re-reading books, articles, and lecture notes; taking new notes and writing practice responses to questions he had provided in advance.

When I remembered the library study sessions, I had an epiphany. There was something about the esoteric nature of the exam topics, and my absence of memory of the details of the materials but clear memory of studying for the test, that led me to really understand — just in time for my 30th Reunion — what I learned in college.

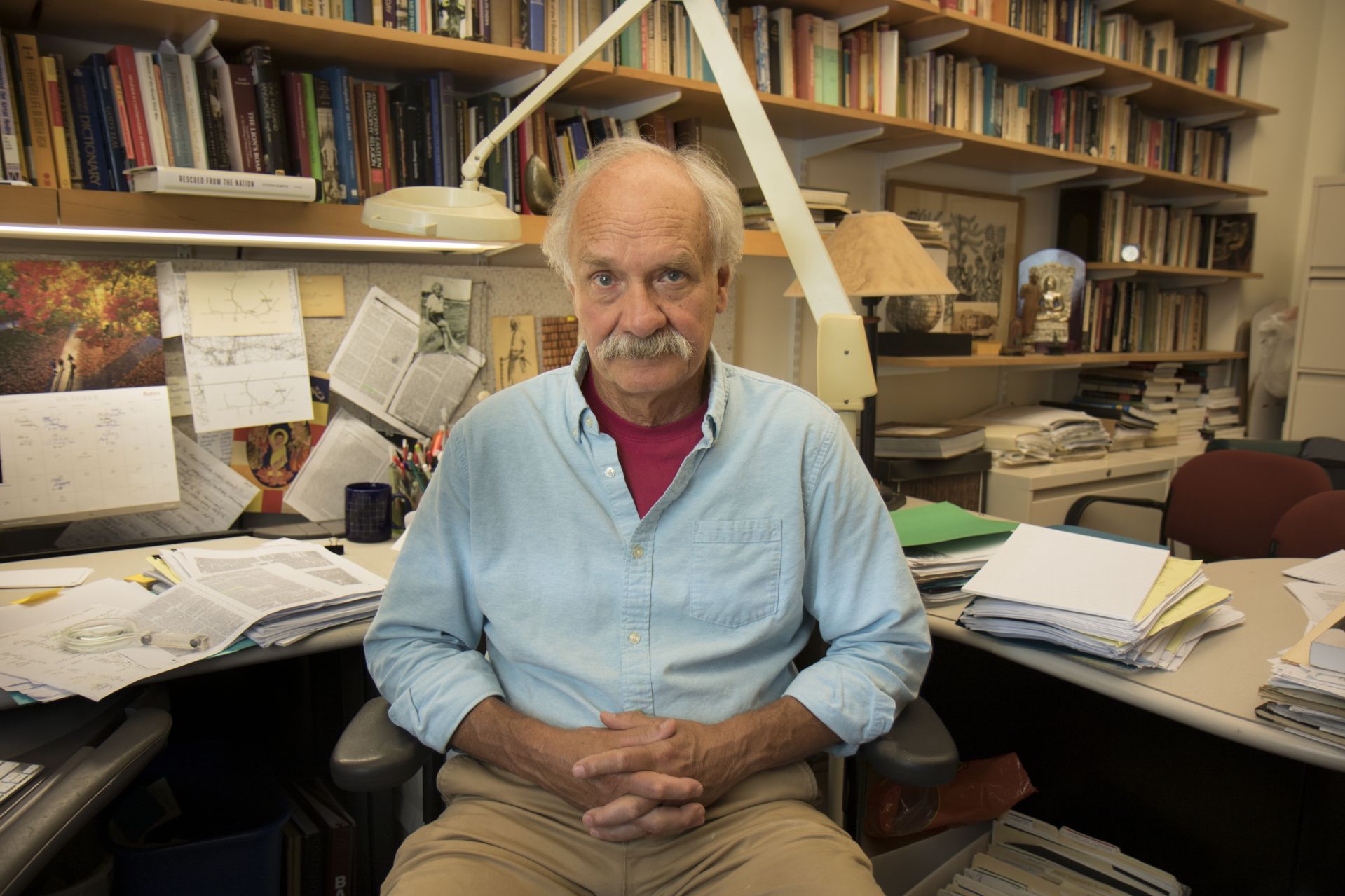

Professor of Anthropology Steven Kemper poses in his office in Pettengill Hall on Sept. 27, 2017. (Samuel Mironko ’21 for Bates College)

Back then, I was focused on the details of the societies Steve instructed us about. I am sure I didn’t appreciate what was at stake, why this kind of learning matters so much.

I now see that Steve helped me to have a genuine interest in people unlike me, and to understand the necessity and value of the hard work of reading, researching, interviewing, seeing, feeling, talking, listening: all in the interest of making sense of how we live in the world, what matters most for people, and why.

From Steve, I learned how to identify what I know and what I don’t know.

In learning about the efforts toward justice by Mahatma Gandhi or by unionized workers in Calcutta, or in learning about menstruation practices among Tamils in Sri Lanka, I developed a lifelong attention to the values, customs, aspirations, and struggles of people near to and far from my daily life. Steve taught me that this kind of learning and understanding is hard but essential work.

Nowadays, I use that conviction to learn and understand, and to make sense of everyday conversations, first-hand experiences, and news items — say, about the Indian government’s revocation of special status for Indian-controlled Kashmir, debates about the separation of migrant families at the U.S.–Mexican border, or the causes and impacts of last spring’s Easter Sunday bombings in my beloved Sri Lanka. From Steve, I learned how to identify what I know and what I don’t know. I learned why it matters that I spend time to learn, humbly and with deep curiosity and respect.

Today I’m an anthropology professor, like Steve. I teach my students how to understand and respect people unlike themselves, and I teach them how this is the road to creating experiences of equity and justice.

Steve has retired from 45 years of transformative education. And yet, his work is not done. During this moment in American life where misunderstanding across communities reigns, educators of my generation and the next must step up and do more of this work.

About Caitrin Lynch ’89

Caitrin Lynch is a cultural anthropologist at Olin College of Engineering.

In 2018, she delivered a TEDx talk about how engineers can incorporate the tools of cultural anthropology in their work to create product and system designs that solve problems and enhance people’s lives.