The world is watching the novel coronavirus outbreak that has killed more than 600 people and infected more than 30,000 in China, and that has now spread to more than 25 other countries, including the U.S.

And of course Bates is watching it too — and finding in this respiratory affliction some important lessons, particularly in how the disease gets around and the role played by individual choices.

During a microbiology class in January, the virus prompted Assistant Professor of Biology Lori Banks and her students to talk about how, in a sense, not all contagion is strictly microbial.

“We talked about how good information vs. unsubstantiated information about outbreaks can change people’s behavior,” she says, “and how you have to be extremely careful in the things that you’re forwarding on social media.

Assistant Professor of Biology Lori Banks advises caution when sharing information about the novel coronavirus. Don’t just forward something along “because it looked sensational.” (Theophil Syslo/Bates College)

“You need to make sure that you’re pulling from a good reputable source and not just forwarding something because it looked sensational.”

The center of the outbreak in China, the city of Wuhan, offers a cautionary tale about the disease of bad information.

“Prior to the major public health machine getting going” and locking down travel in and out of the city, Banks says, “these sensational messages that were getting out caused something like 5 million people to evacuate,” many of them especially anxious to travel during the Chinese Lunar New Year. This during the eruption of a virus whose incubation period can take up to two weeks.

“So imagine if you were at the back end of that, and now you’ve traveled halfway around the world,” says Banks. “You could have been shedding virus, but asymptomatic, for almost two weeks before you would know that you were sick. So not the best idea.”

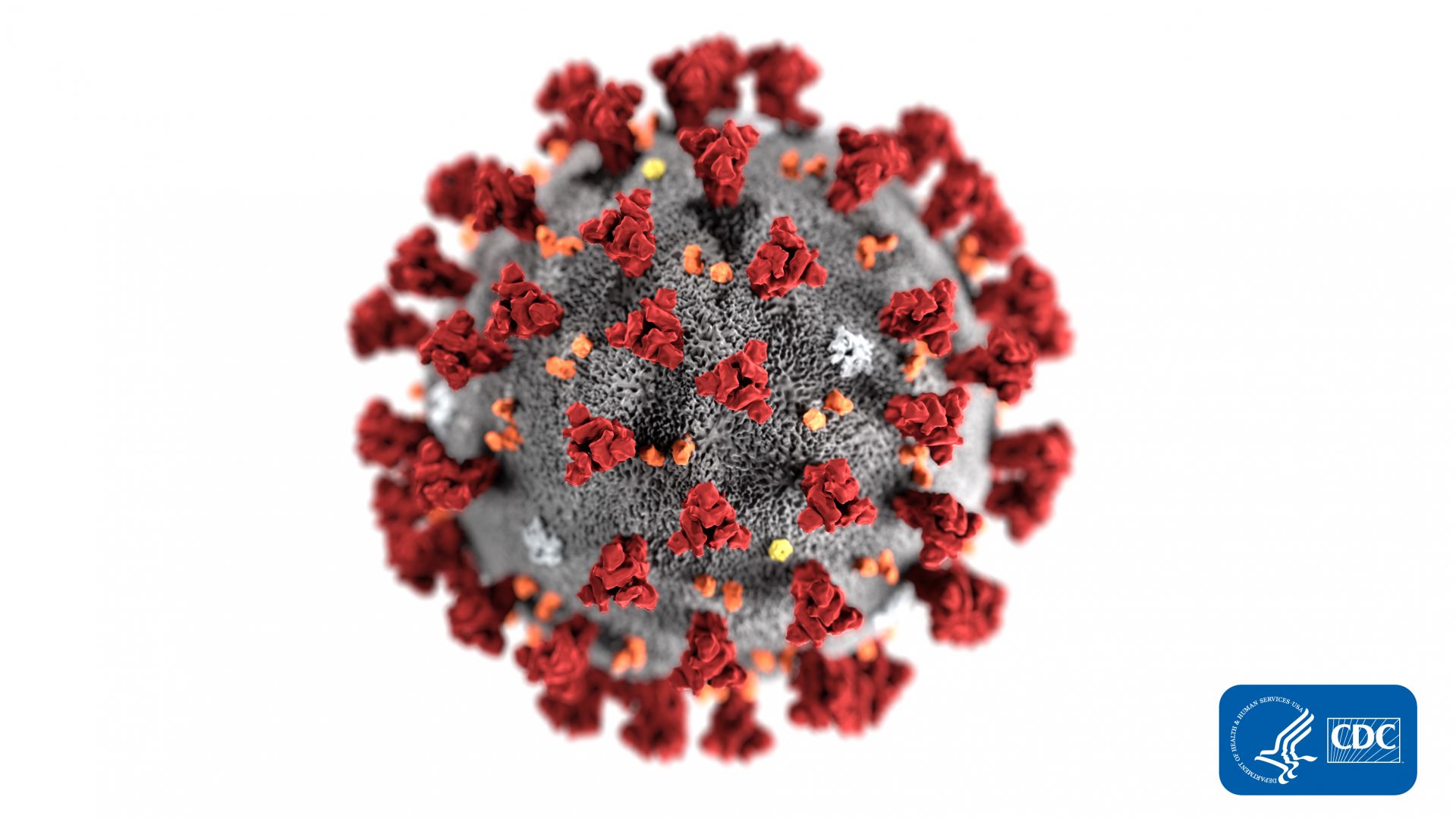

This Centers for Disease Control and Prevention illustration shows the spikes that adorn the outer surface of the 2019 novel coronavirus, which impart the look of a corona when viewed electron microscopically, hence the name “coronavirus.” (Alissa Eckert, MS, Dan Higgins, MAM)

The coronavirus outbreak has proven especially relevant to a senior seminar on biomathematics taught by Associate Professor of Mathematics Meredith Greer, whose published research helped to shed light on the spread of the 2009 H1N1 “swine flu” virus at Bates and elsewhere in 2009.

Greer’s students research and present topics related to biological applications of math, including modeling the spread of disease.

“This is a type of math that closely relates to other aspects of our lives and international life,” Greer told her students during a class session in late January. Mathematicians and public health officials deploy a variety of models to predict the spread and impact of disease.

For instance, a model that Greer has taught in the seminar uses differential equations, which are used to quantify change, to estimate how many people might catch a disease, as well as to predict its geographical spread.

The factors that drive a disease model include the length of the incubation period, the duration of typical infections, the population of the area where the disease first breaks out, and travel patterns.

Meredith Greer and students in a Hathorn Hall classroom during a January meeting of Greer’s course “Advanced Topics in Biomathematics.” (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

“Air travel makes it possible for people to go pretty far pretty quickly, so the disease can go anywhere pretty fast,” Greer told the class.

Xuchong Shao ’20 of Shanghai put a fine point on the importance of the calendar in the spread of disease. The Lunar New Year, which took place at the end of January, is “pretty much like Thanksgiving break in the U.S.,” he said. “Everyone’s traveling to their home.”

“These questions of encouraging or discouraging travel have a big effect on disease spread, but it’s also really relevant to people’s customs,” Greer said. “There are not easy answers.”

If modeling can predict the spread of a disease, it can also tip off officials that their reporting might be off. In the case of novel coronavirus, that could happen because its symptoms can resemble a cold (also often brought to you by a coronavirus, albeit a different species) or influenza. And such cases might not be reported.

“If distances to which it’s spread or the rate of spread are inconsistent with the total number of people who are reported as being sick, that would be a clue that maybe not enough people have been reported as being sick,” Greer said.

Meredith Greer responds to a student’s remark during a session of “Advanced Topics in Biomathematics.” (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

At any rate, Greer told her class, it may be too early for a reliable model of novel coronavirus. Mathematicians, epidemiologists, and public health officials might have to compare and interrogate several models before a clear picture emerges.

As Lori Banks reminds us, influenza “is really a bigger public health concern.”

As always, it’s the unknown that’s the most unsettling aspect of a disease like novel coronavirus, and previously its coronavirus cousins, SARS and MERS. “They don’t know why it’s spreading,” Greer said. “They don’t know how many people will get it, or how many people will die, or how far around the globe it will spread.”

But all things in proportion.

As Lori Banks reminds us, influenza “is really a bigger public health concern. The good news is the precautions that people should take to prevent both of those viruses, both flu and novel coronavirus, are about the same” — wash your hands, cover your cough, don’t share food, don’t go blessing your friends and classmates with your presence when you’re feeling seedy.

But there’s one important difference, Banks notes. “If someone is exhibiting symptoms of a respiratory infection, and they’re sick enough to see a medical professional, they should probably call ahead” to allow that medical practice to prepare, just in case the culprit is novel coronavirus.