In celebration of Women’s History Month, we share stories of these accomplished and pioneering Bates women from the first century of the college — writers, scientists, artists, social-justice activists, doctors, academics, and a Marine.

Disclaimer: Is our list definitive? Hardly! But it’s a labor of respect and admiration, however incomplete.

Thanks, Alex!

Bates senior Alexandra Cullen, a Bates Communications student assistant — and an accomplished Bates woman in her own right — did much of the research on this story.

Mary W. Mitchell, Class of 1869

1846–1898

Indefatigable first female graduate of Bates

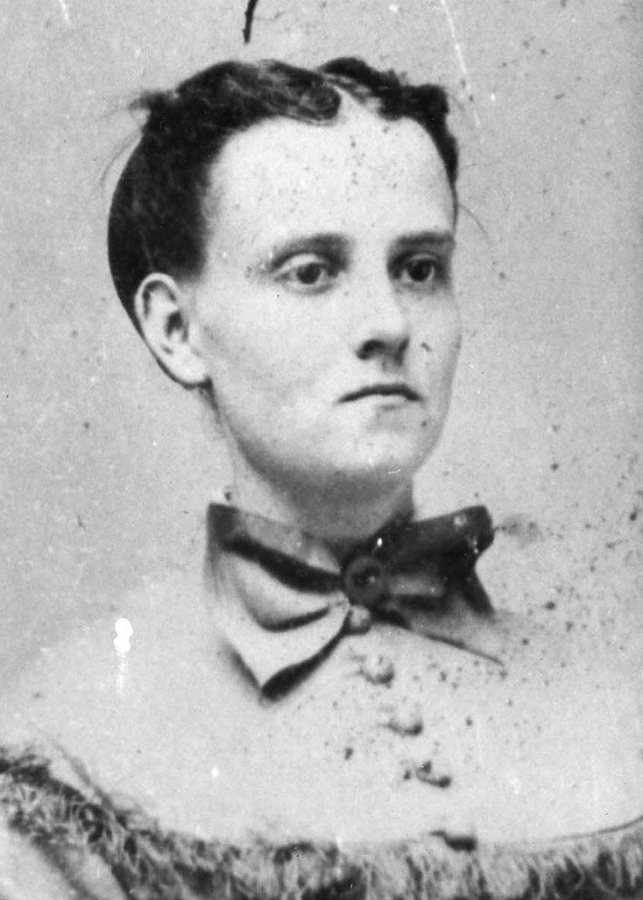

Mary Mitchell was the first female graduate of Bates College, a member of the Class of 1869. Born in 1846 in Dover-Foxcroft, Maine, she was remembered as independent and resourceful, working in the Lewiston cotton mills to pay her way through college and help her family.

Offered a scholarship by Bates founder Oren Cheney, Mitchell famously turned it down: “I cannot take that, Mr. Cheney. Give it to the brethren. I can take care of myself.”

Though Bates was open to women from its beginning, the reality of coeducation was slow to arrive. The initial 14 Bates graduates, in 1867 and 1868, were men. Eight women were non-graduates in that span.

Resistance to women came from inside the college and outside.

Bates President George Colby Chase, Class of 1868, later wrote that “some of those in authority had a subtle influence upon them to the effect that they began to regard themselves as out of place in college.”

Cheney observed that his college, in order to become the first coed college in New England, would have “to brave the criticisms from other institutions because of what would be called an erratic course.”

Indeed, as Tim Larson ‘05 notes in his senior honors thesis, Faith By Their Works, “All male colleges, such as Bowdoin, used the early female graduates of Bates as a means of de-legitimizing the school during this period.”

After graduation, Mitchell taught school in Worcester, Mass., and then, in 1876, became a professor of Latin at Vassar College. She later opened a school for girls in Boston before teaching school in New Hampshire. She was married to Frank Birchall.

At Bates, the residence Mitchell House, at 250 College St., is named for her.

Ella Knowles, Class of 1884

1860–1911

A trailblazing Western woman of many firsts

An American woman, especially a suffragist, who tried to rock society’s boat in the 19th century got a label: “a dangerous woman.”

Meet Bates’ most dangerous woman, Ella Knowles, Class of 1884 — a suffragist, trailblazing and highly successful lawyer, and career boat-rocker whose life was a succession of singular female accomplishments.

At Bates, she was the first woman:

- to win the prestigious Sophomore Championship Debate

- to serve on the editorial board of The Bates Student

After Bates, she moved to Montana, where she was the first American woman:

- to address a state legislature

- to be nominated by a major political party for statewide office

- to be appointed assistant or deputy state attorney general

- to argue a case before the state Supreme Court

- to represent a U.S. state before a federal agency in Washington, D.C.

In 1892, Knowles was nominated by the Populist Party to run for attorney general of Montana, only the second woman in American history to be nominated for that office.

On the campaign trail, she became well-known for her rousing rhetoric in support of women’s rights. She said to one audience:

“Degrade woman, cripple her faculties, hamper her intellectual growth, and the result is a degraded, crippled, or enslaved people. [But] elevate woman, give her full freedom to use the faculties God has given her, not as a matter of favor, but as an act of simple justice [and the] result is a people strong and self-reliant, intellectual, and valiant.”

Mary N. Chase, Class of 1887

1864–1959

She moved the New England suffrage movement forward

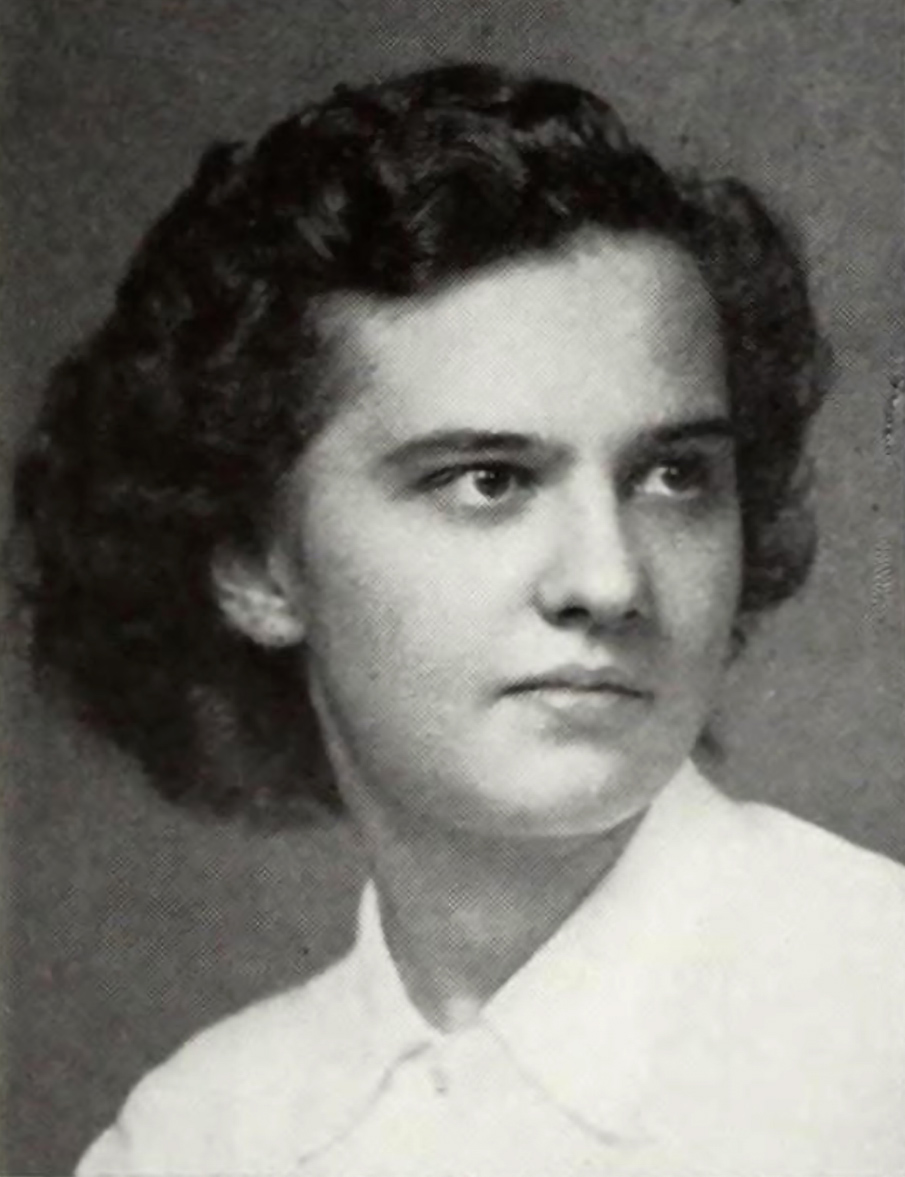

Mary N. Chase, Class of 1887, was a leading figure in the women’s suffrage movement and post–World War I campaigns for international peace.

At Bates, Chase won a scholarship through a declamation contest. She taught school for several years after graduation, but by the turn of the 20th century had become involved in the burgeoning suffrage movement. She organized for the National Woman Suffrage Association and led the New Hampshire Woman Suffrage Association.

Chase put her oratory skills to good use in her activism, speaking at hundreds of local chapters of the Grange, a national agricultural movement that had become an engine of progressive politics.

She garnered support for an amendment to remove the word “male” from the voting rights section of the New Hampshire Constitution.

Chase later worked at Proctor Academy in Andover, N.H., and, as she wrote in 1921, used “International Correspondence to promote International Good Will.” In the wake of the ravages of World War I, she had her students write letters to their counterparts in Mexico, Japan, and Germany, among other countries.

“Already I feel more than repaid for the anxious hours and the hard labor I have put into this endeavor to help heal the wounds of war through the blessed ‘ministry of reconciliation,’” she wrote.

Mary Brackett Robertson, Class of 1890

1868–1962

One of Bates’ first female trustees and a national leader of an organization supporting disadvantaged women

An advocate for disadvantaged women and their children, Mary Brackett Robertson, Class of 1890, twice served as president of the Florence Crittenton Home for Girls in Washington, D.C.

The home was part of a national mission founded in the late 19th century by Charles Crittenton and Dr. Kate Waller Barrett. (Today the organization is known as National Crittenton.)

Robertson served as president of the so-called Lady Managers of the Washington home from 1916 to 1921 and again from 1923 to at least 1933. She was instrumental in “developing the [facility] into a model institution,” wrote Otto Wilson in a history of the Crittenton homes. Robertson was also influential in the national organization.

In 1937, the Mary B. Robertson Fund was established “to ensure that no girl or woman would ever be turned away from the home because she lacked money to pay for its services,” Martha Fletcher ’28 reported in the Bates Alumnus. “Mrs. Robertson rates this as the highest honor she has received.”

Robertson was the daughter of the Rev. Nathan Cook Brackett, a minister of New England’s Free Will Baptist Church and the founder and first president of Storer College, a Historically Black College in West Virginia.

In 1916, Robertson was appointed president of the College Women’s Club of Washington, forerunner of the American Association of University Women. She became one of Bates’ first two women trustees in 1917 (the other was Mrs. Scott Wilson, Class of 1891, also appointed in 1917).

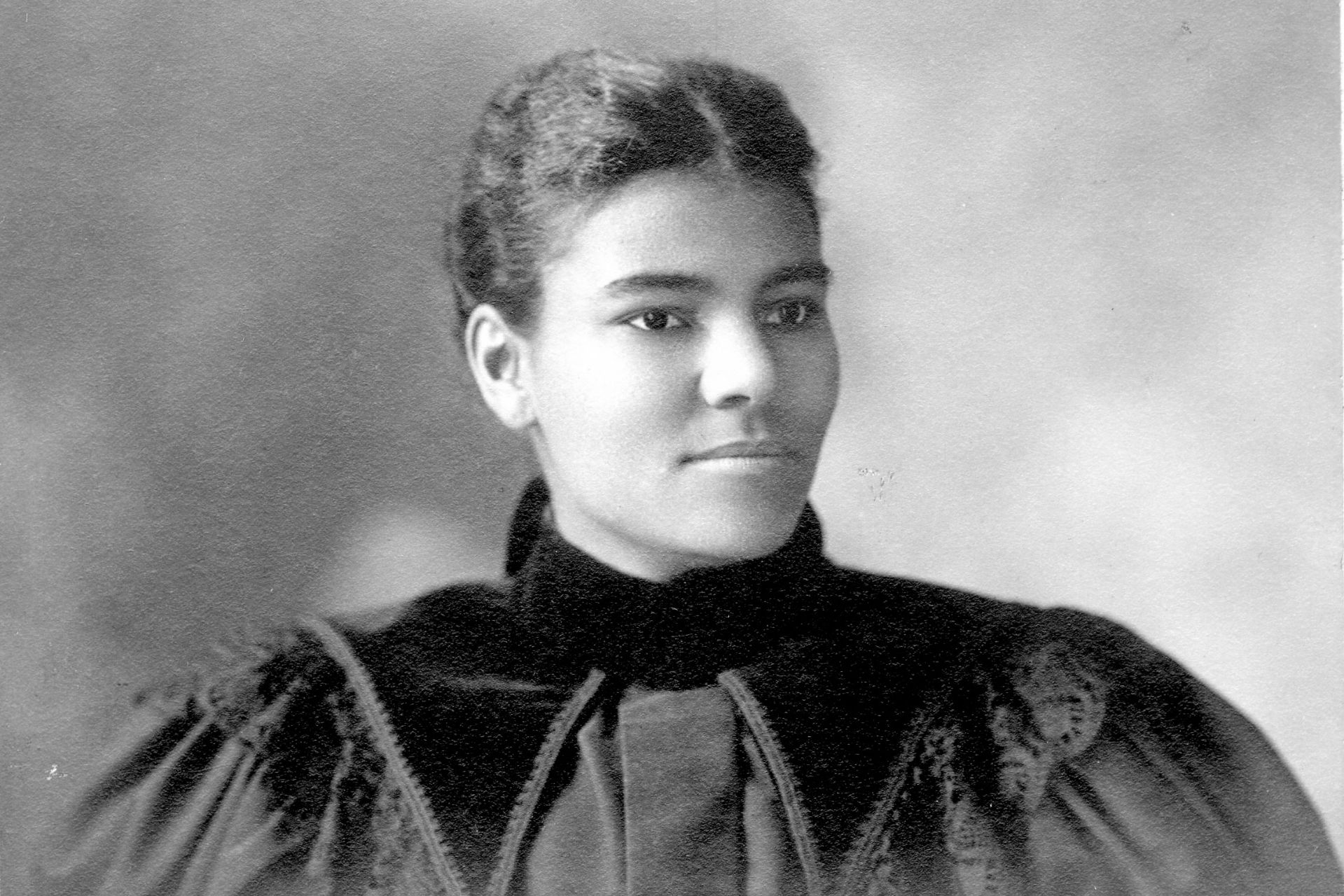

Stella James Sims, Class of 1897

1875–1963

Bates’ first female Black graduate, educator, National Society for Black Physicists member

A member of the Class of 1897, Stella James was Bates’ first Black female graduate. The year she graduated, she wrote eloquently in The Bates Student of the manifold significance of Harpers Ferry, W.Va. This geological wonder, she writes, is a Gibraltar-like formation “lying somewhere between the present and the past.”

And she refers to John Brown’s historic 1859 uprising there, intended to bring on abolition — “the first blow against slavery, and at Charlestown its first martyr was tried and hung.”

James had already earned a degree from a teacher’s school in Harpers Ferry, Storer Normal School, before coming to Bates, earning second honor in physics (students did not major in subjects as we know it today).

Linking the schools was Bates founder Oren Cheney, who encouraged Maine philanthropist John Storer to make a $10,000 gift that enabled an erstwhile Harpers Ferry primary school to evolve into a college to train much-needed Black teachers.

James would marry another Storer graduate, Robert P. Sims, and they raised six children. She taught science and physics at Storer, Virginia Seminary, and finally at Bluefield State College, where her husband was president.

Her writings, whether on Harpers Ferry or the value of manual labor and the need for its instruction at a public school level (“…we want our school training to bear some relation to the probable life work of all”) are remarkable in their clarity, precision and boldly practical thinking. She retired to a farm in Pennsylvania, where she lived to be 88. Her grave is in Harpers Ferry.

Josephine B. Neal, Class of 1901

1880–1955

Physician and medical researcher who fought infectious diseases

Josephine B. Neal, Class of 1901, was a medical doctor and infectious disease expert who researched encephalitis, meningitis, and perhaps most notably, infantile paralysis, later known as polio.

Neal studied physics at Bates and after graduation was listed in The Bates Student among fewer than a dozen faculty members as a “physics assistant.”

She worked as a teacher to pay her way through medical school at Cornell. Several years later she moved to New York City and joined Columbia University’s College of Physicians and Surgeons as a clinical professor of neurology.

Neal authored many academic studies and wrote the book The Clinical Study of Encephalitis, as well as chapters on meningitis in two widely used medical textbooks.

Through the New York City health department, she worked on the front lines fighting polio in the 1920s and ’30s, a time when the disease was a pandemic in North America. In 1934, she was one of a few physicians to receive an experimental polio inoculation (an effective polio vaccine was still years away).

“We cannot yet prevent the disease, nor have we found a cure, but we do know a great deal about treating the victims,” Neal told an interviewer in 1938, the year funds raised at a birthday party for Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who had been disabled by the disease, helped establish a polio foundation.

Among Neal’s many honors were a 1926 honorary degree from Bates and, in recognition of her work on encephalitis, the Elizabeth Blackwell Citation from the New York Infirmary for Women and Children.

Dora Shaw Heffner, Class of 1906

1885–1957

Wielded her legal expertise for social betterment

Daughter of a Maine state attorney general, and one of three siblings renowned for their legal accomplishments, Dora Shaw Heffner, Class of 1906, reached the epitome of her career during her time as head of California’s Department of Mental Hygiene.

Appointed to the position by Gov. Earl Warren in 1943, Heffner supervised all state institutions for the mentally ill and developmentally disabled.

“She believes that mental illness should be treated with care and intelligence and not be looked upon as a shame and disgrace,” wrote Lucile Foulger ’32 in a Bates Alumnus profile.

Heffner was especially effective at attracting state funding for her department, winning support for new facilities and for bolstering professional staff at existing institutions.

A product of her time, Heffner sought to roll back, not eliminate, compulsory sterilization of certain patients. Yet she did seek “a more scientifically informed and democratic approach to institutionalized care [and] created some latitude for patient communication and appeal,” writes Alexandra Minna Stern in the study Eugenic Nation.

Heffner served as a judge in the Los Angeles juvenile court and as commissioner of the state Superior Court for Los Angeles County. She helped organize and run the local Legal Aid Clinic Association, and served as president of the Los Angeles Crittenton Home, part of a national support network for disadvantaged women.

Bates awarded Heffner an honorary degree in 1940. In 1945, she christened the Victory Ship Bates Victory, named for the college.

Elisabeth Anthony Dexter, Class of 1908

1887–1972

Helped refugees flee Nazi persecution during World War II

Elisabeth Anthony Dexter, Class of 1908, organized relief and visa assistance for Jewish refugees fleeing Europe during World War II.

A great-niece of pioneering feminist Susan B. Anthony, Dexter earned a doctorate in history from Clark University and became a well-respected social historian. She wrote a book on women in business during the U.S. Colonial period.

But in the late 1930s, Dexter and her husband, Robert, were attentive to more-contemporary concerns as persecution of Jews by the Nazis in Germany, Austria, and Czechoslovakia was mounting.

Elisabeth and Robert, a leader in the Unitarian church, moved to Portugal to run the Unitarian (now Unitarian Universalist) Service Committee, which helped a growing number of refugees through social assistance, American visa sponsorship, and underground escape routes.

Over the course of the war, Elisabeth Dexter became the committee’s European director — and was even recruited by the U.S. Office of Strategic Services as a spy.

One of the people the Dexters helped immigrate to the United States was Hans Subak, whose daughter Susan later wrote a book about the work of the Unitarian Service Committee. The Dexters also tried to bring over Hans Subak’s parents, but they were unsuccessful. “A sense of guilt sat heavily on them for a long time and was never entirely lifted,” Susan Subak wrote.

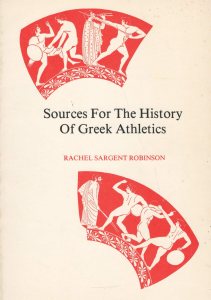

Rachel Sargent Robinson, Class of 1914

1891–1977

Classicist who contributed to our understanding of Greek slavery and athletics

Through teaching, Rachel Sargent Robinson, Class of 1914, funded her bachelor’s degree at Bates and then her doctorate at the University of Illinois. Her dissertation on Greek slavery won her a fellowship to conduct research in Greece.

She worked as a university professor before marrying another classical scholar, Rodney Potter Robinson; they were fixtures at the University of Cincinnati and the American Academy in Rome.

Rachel Robinson continued her scholarship, publishing the oft-cited Sources for the History of Greek Athletics.

After her husband died, Robinson returned to teaching at several universities while working on a comprehensive study of Greek and Roman athletics.

“She regarded each meeting of a class as a performance for which she prepared as if she were the protagonist in a continuing drama,” a University of Cincinnati colleague wrote after Robinson’s death in 1977.

“Her students responded to her own love of learning and enthusiasm for all things of the mind.”

Florence Hooper Moulton, Class of 1915

1894–1956

Missionary who established schools and libraries in India, as well as fostering entrepreneurship

Born in Raymond, Maine, Florence Hooper Moulton, Class of 1915, played hockey at Bates, majored in Latin and history, and graduated with her future husband, Joseph Langdon Moulton.

They were Congregationalists, and a desire to serve brought them to India as missionaries in 1919. And there they stayed, Florence leaving only shortly before her death, in 1956. They were members of the American Board of Foreign Missions.

Their primary assignment in India was to establish and run schools and libraries, as well as fighting famine and improving living conditions. That included helping foster a textile business, the Sisal Fibre Institute, producing sisal products made from hemp.

Moulton was one of many missionaries who helped promote these products within India to foreign customers, but after the partition of 1947, separating India and Pakistan into two countries, that business collapsed.

Stepping in as director, she worked to develop a market for the sisal products among Congregationalists and others back in the U.S. By 1953, as her husband recalled in Faith for the Future, his history of the mission, “orders were coming thick and fast.”

Florence Hooper dedicated her life to others, and had four daughters in the midst of that service. Three of them were Bates graduates: the late Marjorie Moulton Perkins ’41, the late Barbara Moulton Scott ’44, and Margrett J. Moulton ’51.

Hazel Hutchins Wilson, Class of 1919

1898–1992

Attained wide acclaim in the mid-20th century as a prize-winning author of children’s books

An academic librarian who for a time was head of circulation for the American Library in Paris, Hazel Hutchins Wilson, Class of 1919, made her name as a children’s book author in 1939 with The Red Dory.

Writing into the early 1970s and amassing a catalog of some 20 titles, Wilson visited a variety of genres, including biography (The Story of Lafayette) and geography (The Seine: River of Paris). Several of her books, including The Red Dory, The Owen Boys, Tall Ships, and Island Summer, were set in Maine, her native state.

But her most popular books were the Herbert series, about a character based on Wilson’s son, Jerome. Herbert was a well-meaning 10-year-old with a knack for getting into mischief.

“Herbert usually does things to excess, with his family egging him on, since his mother told him that discouraging children is a bad idea!” Wilson’s publisher, Alfred A. Knopf, noted in publicity materials.

Wilson received a variety of accolades for her writing, including the Boys’ Clubs of America Junior Book Award for Thad Owen and the 1955 New York Herald Tribune Spring Book Festival Honor Award for Herbert. Bates awarded Wilson an honorary master of arts degree in 1956.

Wilson also taught courses about children’s literature in the 1950s at George Washington University, where she was a lecturer, and reviewed books for the Washington Evening Star.

Euterpe Boukis Dukakis, Class of 1925

1903–2003

First Greek-American woman to go away to college, lifetime supporter of Bates

Her life began in Larissa, Greece, in 1903 and ended, nearly a full century later, in America. In between, Euterpe Boukis Dukakis ’25 blazed a trail for immigrants, becoming the first Greek-American woman to attend a U.S. college away from home.

A brilliant and diligent student who came to Bates from Haverhill, Mass., where her immigrant family settled, she engaged in extracurricular activities, earned membership in Phi Beta Kappa, and remained loyal to Bates her entire life, establishing in 1994 the endowed Euterpe B. Dukakis Professorship in Classical and Medieval Studies.

Her success led the way for other Bates students from immigrant families; the late Trustee emerita Helen Papaioanou ’49 recalls, as a student, briefly meeting Dukakis and her husband, Panos ’22:

“She said to me, ‘We are proud of you!’ In that moment, there was an acknowledgment of connectedness, of heritage, experience, struggles, dreams and aspirations.”

In her mid-80s, the woman her classmates nicknamed “Zippy” proved again her intellect and mettle, campaigning for her son, Michael, the 1988 Democratic nominee for president. She flew to events around the country, spoke to senior-citizen groups and sat for media interviews.

She once said about growing old, “Get my body, but don’t take my curiosity,” and, in Greek, she expressed love for her family this way: “I love you. I love you, like my own two eyes.”

Alice Swanson Esty, Class of 1925

1904–2000

New York City arts patron also committed to music at Bates

The day before leaving the farming community of Thomaston, Conn., for Lewiston, Alice Swanson Esty ’25 called a high school mentor. “I’m $25 short. I can’t get there,” she told the teacher. He supplied the necessary funds; for Esty, it proved to an unforgettable act of kindness and philanthropy.

After graduation from Bates, Esty moved to New York City to pursue a performing arts career. She worked with influential directors Lee Strasberg and Harold Clurman and with the avant-garde Provincetown Players, ultimately appearing on Broadway in Come of Age with Judith Anderson and L’Aiglon with Ethel Barrymore.

While marriage to William C. Esty, founder of the eponymous advertising agency, transformed her from struggling artist to patron of the arts, she continued to pursue an interest she had gained at Bates, studying voice with Juilliard teacher Florence Kimball Paige.

Esty established the college’s Alice Swanson Esty Professorship in Music in 1997 and gave Bates valuable books, manuscripts, and musical scores she had commissioned and performed.

Supporting music at Bates, said Esty, “is going to make better musicians whether they go on with their big careers or have a smaller career. If students have the opportunity to study music along with their other studies, they would have an actually better life.”

In 1984 she received an honorary Doctor of Humane Letters degree from Bates “in gratitude for her example of generous and bold patronage of the arts and artists, but even more in celebration of her gifts of song and her grace of self.”

Dorothy Clarke Wilson, Class of 1925

1904–2003

Prominent and prolific author, playwright, and social justice advocate

“Flimflammery” is how writer Dorothy Clarke Wilson ’25 described the scene in The Ten Commandments where Moses, played by Charleton Heston, parts the Red Sea. She would know: Her novel about the early life of Moses, The Prince of Egypt, which earned the Westminster Award for Fiction in 1948, was a key source for Cecil B. DeMille’s 1956 Hollywood epic.

Wilson was one of three writers from her class to attain national prominence, the others being Erwin Canham, editor of the Christian Science Monitor, and novelist Gladys Hasty Carroll.

Bates Magazine obituary writer Christine Terp Madsen ’73 wrote that Wilson “combined the urge and talent to write, a deep faith, and an intense concern for social justice” in all her work.

Wilson wrote some 70 plays on religious themes and more than 30 books in various genres. In 1949, stated the Bangor Daily News, “she was recognized as having more plays in production than any other playwright in the world.”

Wilson wrote what she called “novelized biographies” about prominent women, including Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell (the first woman granted an M.D. in this country), Martha Custis Washington, Abraham Lincoln’s mother and stepmother, and the two wives of Theodore Roosevelt. She also wrote several books about people with profound disabilities.

She received a Doctor of Letters degree from Bates in 1947, and a Doctor of Humane Letters degree from the University of Maine in 1984.

Gladys Hasty Carroll, Class of 1925

1904–1999

Author of a best-selling novel that immortalized a rural Maine culture

Daughter of a close-knit family living on a Maine farm, Gladys Hasty Carroll ’25 parlayed this upbringing into literary stardom in 1933 with the publication of As the Earth Turns.

A Book-of-the-Month selection and Pulitzer nominee, the novel brought readers through a year in the life of a family in Dunnybrook, based on a hamlet in the author’s hometown, South Berwick.

Carroll’s best-seller “is a highly regarded evocation of an era that is rapidly fading from living memory,” wrote a Portland Press Herald reporter. “At the heart of the work lies a dignity and resilience in the face of change that…[Carroll] always defended as an accurate portrayal of a life she had seen and lived.”

Though she never again enjoyed the level of success she earned with As the Earth Turns, Carroll continued to write into the 1970s, completing 26 books of fiction and nonfiction, including short stories and children’s books.

She received an honorary degree from Bates in 1945 and served on the Board of Overseers from 1950 to 1955. The University of Maine presented her with the 1995 Maryann Hartman Award, recognizing exemplary “spirit, achievement, and zest for life” among Maine women.

Priscilla Lunderville, Class of 1929

1907–1985

Launched a greeting card company that ultimately attracted millions of customers worldwide

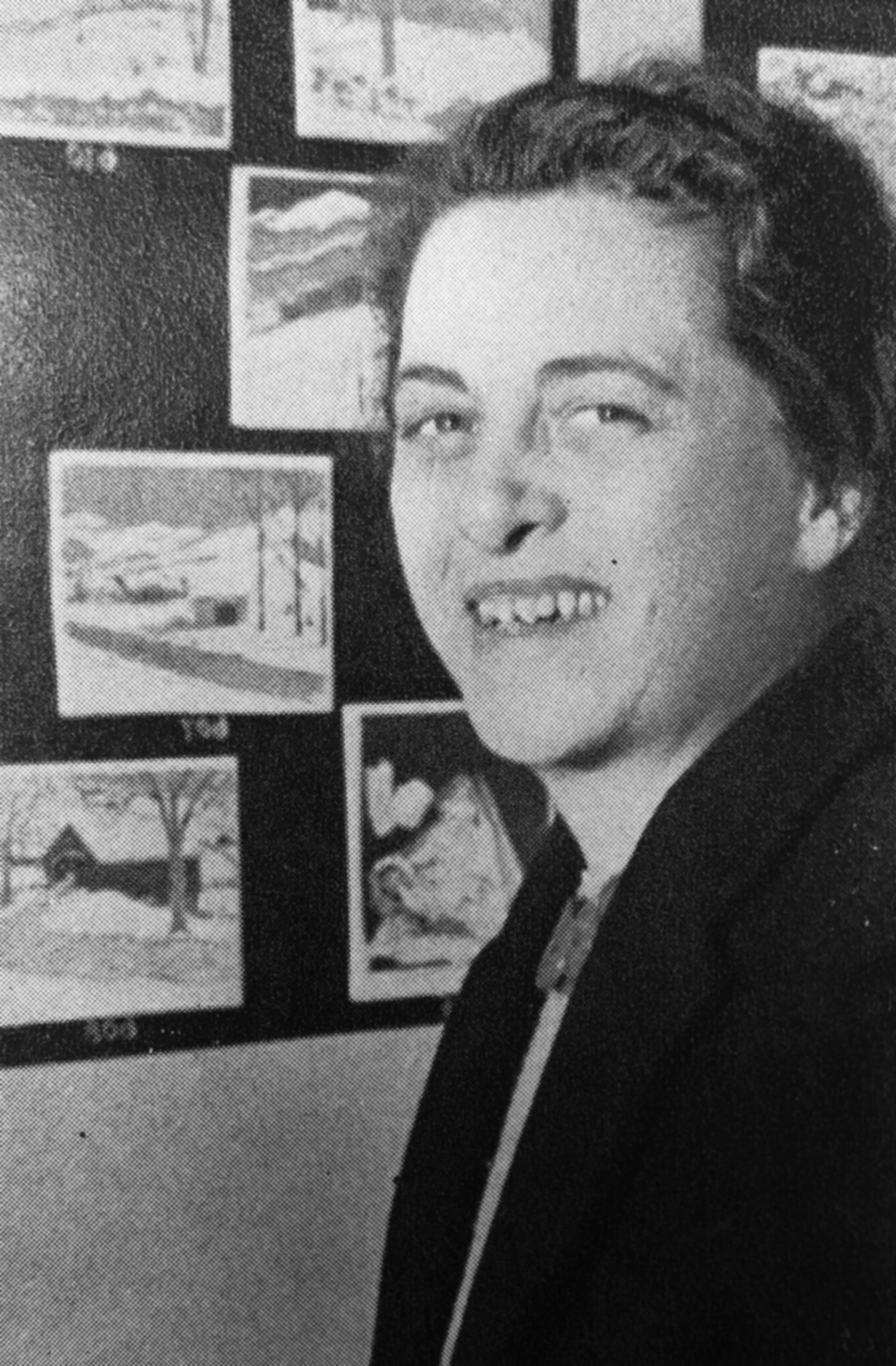

Though she was known as a Bates student for her musical accomplishments, it was in the realm of commercial art and publishing that Priscilla Lunderville ’29 found her greatest success.

Teaching in small towns for a few years after Bates, she “discovered she had a latent talent for designing greeting cards,” Reginald Colby ’31 wrote in a 1949 Bates Alumnus profile of Lunderville.

“A happier discovery was that people would buy them. She left the teaching profession and, starting with a few hard-drawn cards for friends and acquaintances, soon interested a local printing firm in producing several thousand copies of a few designs to retail for five cents.”

Her designs, which emphasized bold colors and traditional imagery, had a broad appeal that drew a rapidly increasing audience. Launching her business, titled Workshop Cards by Priscilla Lunderville, in her hometown of Littleton, N.H., Lunderville quickly found herself needing more space and more employees to meet demand.

Later incorporated as Workshop Cards Inc., with Lunderville as president, the firm’s reach expanded nationally and beyond. “The cards flow out to buyers through some 1,600 accounts in 42 states, South Africa, Alaska and Hawaii,” Colby pointed out.

Lunderville didn’t forget Bates. As Colby divulged in his profile, Workshop’s “Notables” line of made-to-order designs for stationery included images of the College Chapel and could be purchased in the College Store.

Mildred Beckman Myhrman, Class of 1930

1909–2001

A lifetime dedicated to social and civic betterment

In her long life, Mildred Beckman Myhrman ’30 compiled an enviable record of social work and public service.

Along with volunteer work for diverse service organizations, that record includes four years as chair of the Disaster Committee of the Lewiston-Auburn Red Cross and time as a psychiatric social worker with the Androscoggin County Mental Health Association and other mental health services.

A magna cum laude graduate of Bates, Mildred Beckman earned a master’s degree in social work from Western Reserve School of Applied Social Services in 1934. In Ohio, she was a caseworker for the Cleveland Family Service Society and held various positions with a county relief administration.

She returned to Lewiston in 1935, married Bates sociology professor Anders Myhrman, and taught sociology at the college as a part-time or occasional instructor until 1948.

From 1957 to 1964, Mildred served the College as a trustee. She and Anders were two of the four people celebrated by Richard Swett when he endowed an award recognizing outstanding sociology theses at Bates. The Myhrman / Swett Award honors Swett’s aunt and uncle, Mildred and Anders; and his parents, Robert Swett ’33 and Muriel Beckman Swett ’30, Mildred’s twin.

Of the twins — known on campus as “Mu” and “Mid” — the 1930 Mirror noted, “Even now, we can’t always tell one from the other. It’s rumored that ‘Mu’ sang in choir one morning and no one knew the difference.”

Iva W. Foster, Class of 1930

1909–1991

The unsung hero of Ladd Library

Iva Foster ’30 succeeded another Bates alumna, the esteemed Mabel Eaton, Class of 1910, as Bates librarian. Eaton herself made significant contributions to Bates — she founded the women’s honor society College Key, which would later be merged with the men’s Bates Club.

And while Foster’s tenure as librarian was shorter than Eaton’s 36 years, she was in charge when Bates tackled one of its most complex and significant building projects: a new library.

“Iva was the unsung hero” of the Ladd Library project, said Bernie Carpenter, treasurer emeritus, in a Bates oral history. “She was so sweet, and at the same time hard as nails.”

Helping to develop a program for the new library, Foster first evaluated the current collection and space.

“Iva went to work and measured all of the linear footage of shelving there was for books in every discipline,” said Carpenter. “She had a yardstick that she ran around with, this 3-foot stick, measuring everything.”

Then she hit the road. “She traveled all over New England and made these long lists of things that had to be considered,” Carpenter said.

Most important, she asked Bates to make hard decisions about possible building features and amenities — “to determine if they were not as necessary for us as for somebody else, or if they did need to be in our new building, to ensure that we didn’t build something that was smaller than we’d have to have.”

“Iva would sit in with all the meetings with the contractors and through the bidding process, and she was right there with a hard hat on, right along with the rest of us.”

The building team was asked to look 20 years into the future. Now, a half-century later, Foster’s work is still paying off.

Marion Crosby Hoppin, Class of 1932

1905–1996

University professor, Jungian therapist, and part of the founding of the New College of Florida

Marion Crosby Hoppin ’32 was a Bates debater, a psychologist, and a forward-looking college administrator who helped found the New College of Florida. “Her great strength as a woman was a great, welcoming tolerance,” Hoppin’s obituary in Bates Magazine quotes a colleague as saying.

Hoppin majored in English at Bates and earned a master’s degree in the subject before pivoting to psychology, earning a doctorate from Columbia. She and her husband, noted film animator Courtland Hector Hoppin, studied under Carl Jung in Switzerland. She was a Bates trustee for 10 years.

Hoppin worked as a professor and administrator at Hunter College and Carleton College before she and her husband moved to Florida, where they got involved with a group planning the establishment of a liberal arts college.

The community of the nascent New College of Florida was incomplete without Hoppin, “a beacon of light in a long gown and surrounded by a cloud of Pekingese dogs,” reads Hoppin’s obituary in the New College’s alumni magazine.

At the college, she taught Jungian psychoanalysis, existentialism, and mythology, and she founded the C. G. Jung Society in Sarasota. A swimming pool at the News College that she funded is named for her; an endowed chair in the Department of Asian Studies is also named after her.

Marjorie Arlington Anderson, Class of 1933

1912–2009

Pioneering African American librarian

Marjorie Arlington Anderson spent her early years in Connecticut and moved to Lewiston at about the age of 10. She lived close to the Bates campus, at 56 Elm St., where her stepfather, George A. Ross, Class of 1904, ran a famous local ice cream parlor.

At Bates, she majored in English, played soccer, and was known as the girl with the “infectious giggle.” After graduation she earned a degree in library science from Simmons College in 1934.

Her first job as a librarian was at an all-Black preparatory school in North Carolina, called the Palmer Memorial Institute (now defunct).

In 1937 the Columbia Civic Library Association published a slim directory (31 pages) of all the black librarians with degrees from accredited library schools: Marjorie Arlington was listed as only the fourth Black graduate of Simmons’ library program.

Citing the directory as the first of its kind, the authors offered it with the hope that it would serve a definite need for “library service to all.”

From there Marjorie Arlington moved to New York. She married Carl C. Anderson in 1941. She worked at the New York Public Library for 31 years, working as a children’s librarian, filling a definite need.

Geneva Kirk, Class of 1937

1917–2007

Educational leader and champion of her home town of Lewiston

One of the most highly engaged civic leaders of her era in Lewiston-Auburn, Geneva Kirk ’37 was once asked what inspired her service. “Bates College,” she said. “The professors kept reminding us that if you had a good education you owed it to society to return some of that.”

A Lewiston native who lived near campus at 30 Ware St. most of her life, Kirk was a career educator who taught at Lewiston High School from 1948 to 1979. She served as president of the Maine Teachers Association and the Maine Retired Teachers Association.

She began teaching at a time when married women were actively discouraged from the profession, she recalled in a Bates oral history.

“Married women couldn’t teach. [Schools] wouldn’t hire them — the city didn’t want to support families. We always had sufficient teachers and perfectly well-qualified teachers, but women felt badly that they couldn’t stay on after they were married.”

Kirk served innumerable nonprofits and professional organizations. She was particularly active with the United Way, whose annual volunteer award is named The Geneva Kirk Award for Community Service. Kirk received an honorary Doctor of Laws degree from Bates in 1993.

Sara Jaffarian, Class of 1937

1915–2013

National leader and advocate for libraries

A member of the Armenian immigrant community of Haverhill, Mass., and the youngest of 10 children, Saranush “Sara” Jaffarian ’37 began her librarian career in the public schools of Quincy, Mass.

She later served as the director of libraries for the Greensboro, N.C., public schools and the supervisor of libraries for the Seattle public schools.

In 1961, Jaffarian returned to Massachusetts to take charge of revising the public school libraries in Lexington.

She held numerous leadership positions with the American Library Association, which sponsors the Sara Jaffarian School Library Program Award, a $5,000 prize for “exemplary programming in the humanities.”

Jaffarian majored in history and government at Bates and earned a library science degree at Simmons College.

“In order to have an excellent school, there must be an excellent school library!” she said.

“To achieve this, more is needed than just books and other materials — curriculum-related programming has the power to take a school library to the next level, exciting students, bringing in parents, and getting the attention of administrators and community leaders.”

Elizabeth Gregory, Class of 1938

1917–2012

The pediatric “fairy godmother” of Arlington, Mass.

A longtime pediatrician and mainstay of the Armenian community of Greater Boston, Dr. Elizabeth Gregory ’38 once said that “Bates is where my life began. Before that I was the daughter of my parents — helped, nourished, directed, encouraged, pushed by them. At Bates, I became an individual who recognized my own ambitions and abilities and knew where I wanted to go.”

Bates Magazine obituary editor Christine Terp Madsen ’73 began Gregory’s obituary this way: “Betty Gregory, the oldest child of parents who fled the murderous hands of Turks intent on wiping out the Armenians among them, never forgot that heritage, that genocide, that sacrifice.”

Gregory’s father, a teacher in Armenia who became a shoe factory manager in Lewiston, put three of his four children through college and graduate school.

Gregory was accepted into Boston University’s medical school “at a time when it was strongly suspected that such studies would shrivel women’s internal organs,” Madsen wrote.

In 1998, one of Gregory’s former patients, Elizabeth Meade ’00, by then a Bates student (whose own parents had been childhood patients of Gregory’s), posed with Gregory for a photograph at Bates.

Said Meade, “Dr. Gregory’s name was brought up so often in my house when I was growing up. When I saw her again at Bates, everything that I had heard about her was confirmed: She was extremely vibrant and witty. With her incredible energy and obvious zest for life, Dr. Gregory could easily keep up with students at Bates today!”

Ellen Craft Dammond, Class of 1938

1916–2007

Preserving and continuing a family history of resistance to racism and slavery

Ellen “Kaye” Craft Dammond ’38 proudly traced her ancestry back to her great-grandparents.

On her paternal side, William and Ellen Craft made a daring escape from slavery via the Underground Railroad in 1848. Ellen disguised herself as a white male slaveholder and boarded a train with William, who posed as her enslaved valet. They later returned to buy the Georgia land that they had worked as slaves.

Dammond’s maternal great-grandparents were slaves of Thomas Jefferson: Joseph Fossett, head blacksmith, and Edith Hern Fossett, head cook. A maternal uncle was William Monroe Trotter, who confronted President Woodrow Wilson over federal discrimination and founded an influential black newspaper in Boston.

As Bates Magazine obituary editor Christine Terp Madsen ’73 noted in Dammond’s obituary, “Kaye herself worked throughout her life to eliminate racism, including chairing a national meeting of black women connected to the YWCA, which resulted in the organization adopting as its goal ‘the elimination of racism.’”

In addition, Dammond was a “prominent figure in the Wednesdays in Mississippi advocacy group that brought Northern and Southern women together to work on issues significant to the Black community.”

Dammond also had a long and successful career as the personnel counselor at B. Altman, the New York City department store that operated, under the stipulations of its founder’s will, to promote the social, physical, and economic welfare of its employees. She was the first “colored girl” (as she described herself) to live in her dorm at Bates.

Aune Helen Martikainen, Class of 1939

1916–2015

An international career in public health education with great impact

“Certainly when the public health history books are written, A. Helen Martikainen will be the name associated with the establishment of fundamental health education in most of the world,” the American Public Health Association stated in 1978, as it honored Martikainen ’39 with its International Award for Excellence.

The award citation focused on Martikainen’s tenure in Switzerland as the World Health Organization’s first chief of health education, a position she took in 1949.

In that role, the APHA noted, this Maine native “became the international symbol of health improvement through health education and people participation. For 25 years, she was the driving force in making health education a working and productive component of health services in many nations.”

To this work Martikainen brought postgraduate degrees in public health from Yale and Harvard, as well as experience as a health education specialist in Hartford, Conn., and with the U.S. Public Health Service.

Health educators were scarce when Martikainen began her career in this country and even by 1949, there was “little or no acceptance of health education in much of the world.”

In 1976, Martikainen was the first woman and second U.S. citizen to receive the International Union for Health Education’s Farisot Medal. Recipient of a 1957 honorary degree from Bates, in 1989 she was honored with the Benjamin E. Mays Medal, the college’s highest alumni award. She remained involved with public service and health education into her 80s.

Marguerite M. Shaw, Class of 1940

1916—1983

Educator with a vibrant side career in performance that took her to Broadway

Born in South Paris, Maine, Marguerite Shaw ’40 had two very different, equally lively careers. In one, she graduated from Bates with a degree in English, earned a master’s at Columbia, and became a dean at American University and a leader in physical education at Sarah Lawrence.

In the other, sandwiched between her academic commitments, Shaw was a successful character actress, performing with the Red Cross during wartime and then joining a company of The Pajama Game (as Mabel, the role that her sister Reta had originated) that toured nationally and internationally before landing on Broadway.

Shaw arrived at Bates in 1938 as a transfer student from Westbrook Junior College. After graduation, she returned to the junior college to teach physical education and performed regularly with the Portland Players.

During World War II, she served with the American Red Cross Recreation Service. Returning to education after the war, she had become dean of women at American University by 1955, when she took a hiatus to pursue theater.

After The Pajama Game’s Broadway run and parts in other musicals, including My Fair Lady, Shaw joined the faculty at Sarah Lawrence College. Her achievements there included starting a men’s basketball team and a softball team.

A note from the Sarah Lawrence archives credits Shaw with bringing a wide sense of fun to phys ed, including lessons in circus skills, flamenco dancing, and scuba diving. Her emphasis was on “enjoying the essence of play inherent in sports rather than the concept of competition.”

Dorothy Dole Johnson, Class of 1941

1918—2019

University anatomy professor and Bates trustee

Bates students whose summer projects are funded through the Dorothy Dole Johnson ’41 Endowment for Science Research benefit from a legacy of cutting-edge research and teaching in the natural sciences.

Johnson, who died last year at the age of 100, grew up on her parents’ dairy farm in New Hampshire and majored in biology at Bates.

She earned a doctorate from Columbia and stayed on at the university for many years as a professor of anatomy, teaching future physicians and surgeons. She co-edited two editions of a histology textbook.

After her retirement, Johnson devoted herself to volunteering. She was a Bates trustee, church member, and volunteer at hospitals and garden clubs.

Barbara White Morris, Class of 1942

1921–2000

As a World War II Marine, stepping up to help with the war

Barbara White Morris ’42 may have thought that producing the play Yes, My Darling Daughter for the officers at Camp Lejeune would be the highlight of her service during World War II.

Commissioned as a first lieutenant in the U.S. Marine Corps Women’s Reserve, Morris was assigned to the recreation department at Camp Lejeune.

Then, “out of a blue sky,” as she told Bates Magazine in 1945, she was put in command of three Pullman cars of women Marines, “our cars being attached to the tail end of a troop train of men bound for the California docks and the South Pacific.”

The train was, she believes, “was the first coeducational troop train in Marine history.” Though the men and women couldn’t socialize, the men, via the train’s porters, “showered us with cases of Coke, games, whole roast chickens, and once even an eight-pound steak.”

Later in the war, as Pacific Theater casualties mounted, Morris took part in efforts to bolster enlistment to the Women’s Reserve in order to free up men for combat duty.

She wrote Lady Leatherneck, part of a “Career Book” series geared to young adults, about a woman’s “induction, training, duty assignment in California, and her romance with Marine Capt. Richard Whiting.” (Morris’ husband, Howe Morris ’45, was also a Marine officer, serving in the Pacific.)

After the war, Barbara Morris became an Maine public school educator who earned master’s degrees from Boston University and the University of Southern Maine.

Edith L. Hary, Class of 1947

1922—2013

Librarian for Maine lawyers, legislators, future vice presidential candidates

As the Maine State Law Librarian, Edith L. Hary ’47 was a top resource to lawyers, legislators, and judges across the state for 35 years.

A government and history major, Hary paid her way through Bates by working at Coram Library. She earned a master’s in library science and found her niche in law, quickly becoming an authority in the field, developing an “encyclopedic” knowledge of legal topics. Lawyers, judges, and politicians like Edmund Muskie ’36 were regular visitors to Hary’s desk.

“Being a law librarian is not making footnotes for book reports; it’s dealing with everyday problems, whether they’re political or legal or whatever,” Hary told an oral history interviewer in 2004. “And it demands a lot of you, and it rewards you, by the interesting things that come up.”

Hary turned the state law library into a circulating library for citizens and was involved in several legal, legislative, and historical organizations, including the Maine State Archive, which she helped establish.

She received an honorary degree from the University of Southern Maine in 1975; an “Edith L. Hary Day” in Maine was proclaimed at least twice.

Faith E. Jensen, Class of 1947

1926—1983

Nurse who specialized in mental health

As a nurse, Faith E. Jensen ’47 concerned herself with psychiatry and mental health, a subject that even in the 1950s was “on the tip of every tongue,” Jensen wrote.

A biology major at Bates, Jensen went on to earn a master’s in nursing at Yale, specializing in child psychiatry. She wrote articles about mental health, as well as parenting, and in 1949 represented Yale at the International Congress of Nurses in Stockholm, Sweden.

Jensen later taught at the University of Mexico College of Nursing and worked with the Albuquerque public school system.

She saw mental health as an integral part of nursing. Of her patients on her rotations as a Yale nursing student, she wrote, “One, a boy with rheumatoid arthritis, was depressed and withdrawn; another, a little girl, was cross, irritated, demanding, and resistive to treatment.

“I realized afresh the many useful opportunities that could be seized to know a patient better — during his bath, a procedure, a meal — instead of waiting for the ‘ideal moment,’ which, in nursing, seldom presents itself.”

Helen A. Papaioanou, Class of 1949

1928–2019

Prominent and persevering pediatrician, role model, and Bates leader

As a Bates senior, high-achieving biology major Helen Papaioanou ’49 interviewed for admission to medical school at Boston University.

The dean challenged Papaioanou, demanding to know if she truly expected to practice medicine. The implication was that a woman would marry after medical school and not go into practice.

She gained admission. “Overall, my experience in medical school was terrific,” Papaioanou told Bates Magazine in 1997. “But there were some disagreeable things.”

Male classmates told her that “men needed to become physicians more than women did. They told me that women in medical school were taking the places that men deserved and needed.”

But she persevered. A native of Springfield, Mass., who was the daughter of a Greek immigrant father and a mother who was the daughter of Italian immigrants, she became a noted pediatrician who specialized in allergies, asthma, and immunology.

Papaioanou practiced in suburban Massachusetts and Michigan before spending a decade serving children in Detroit at Children’s Hospital of Michigan and doing research, as well. “I wanted to be working where medical and social needs simply were not being met,” she said of her time in inner-city Detroit.

She was one of the most engaged Bates volunteers of her era. She was a Bates trustee from 1965 to 1999. She served as national chair of the 1991–96 comprehensive fundraising campaign and, in 2003, received the college’s highest alumni honor, the Benjamin E. Mays Medal. In 1999, Ralph Perry ’51 and Mary Louise Seldenfleur endowed a professorship in the biological sciences in Helen’s honor.

The citation for Papaioanou’s 1997 honorary Doctor of Science degree praised her “witness to the power of love and science in service to others, her integrity and relentless optimism, the model she has been for other women to pursue science at Bates, and her ability to draw the friends and graduates of this college together to serve present and future students.”

Marian Goddard Mullet, Class of 1950

1927–2019

Advocate, educator, and visionary for people with Down syndrome

Marian Goddard Mullet, a member of the last Bates nursing class, moved with her husband, Frank ’47, to central New York in 1963. The Hartford, Conn., native was a busy mother, raising four children, when she decided to take on a volunteer role, using her nursing training at the nearby Otsego School, a facility for children and adults with Down syndrome.

She witnessed plenty of love and care for the residents but was acutely aware that they “were literally raised behind a fence,” Mullet told Phyllis Graber Jensen in a 1999 Bates Magazine profile. “The true opportunity to grow physically and mentally [was] nonexistent.”

By 1976, Mullet had an unexpected chance to change that. As described by Bates Magazine obituary editor Christine Terp Madsen ’73 in her obituary for Mullet, the school had to reinvent itself due to changes in the law.

At a key meeting of school officials, Mullet, by then an employee, “realized with surprise and dread that everyone was depending on her…to devise a plan for a new facility. With no money, no land, and no buildings, she took on the task and built Pathfinder Village in Edmeston, N.Y., an internationally renowned residential campus and service provider for people with developmental disabilities.”

The first organization of its kind for people with Down syndrome, today it is considered a global leader in human services and supports more than 200 individuals, has a staff of more than 200, and an annual budget of $11 million.

Pathfinder Village’s philosophy is “where each life finds meaning” and caring, independence, and integration into the greater community were absolute necessities, Mullet said, as were friendships and love affairs. No more fences. No talk of “institutions.” She made Pathfinder Village a community.

“Marian Mullet is not an empire builder. She simply feels she did what had to be done to help her friends,” her younger brother Stephen Goddard ’63 wrote in a 1988 New York Times op-ed that appeared the day she received an honorary doctorate of laws from Bates.