A Bates biology professor has a notable role in responding to one of the tough problems created by COVID-19: the shortage of personal protective equipment, or PPE, for health workers and first responders.

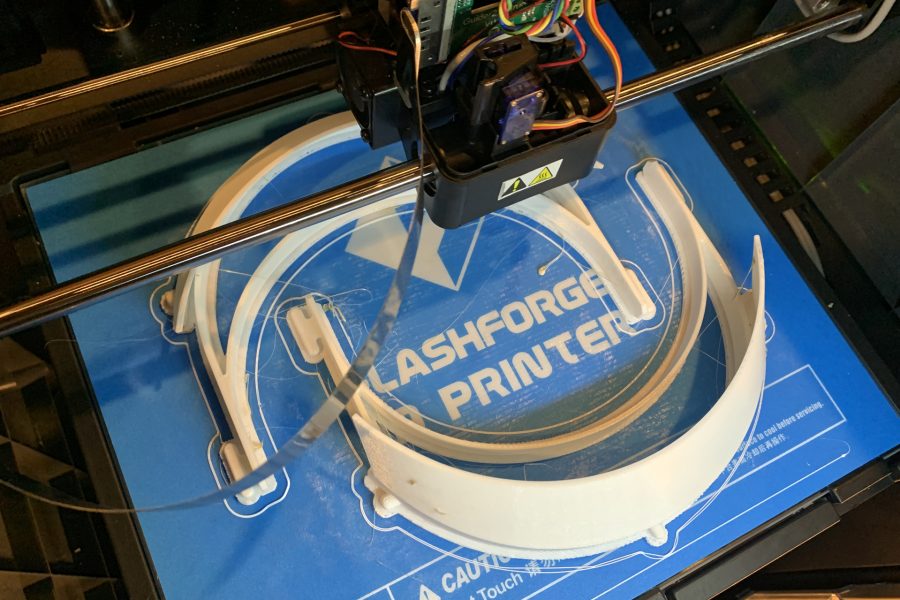

Andrew Mountcastle, an assistant professor of biology whose teaching and research often employ three-dimensional printing, is among staff and faculty at three Maine colleges who are using three-dimensional printers to make PPE components.

During the past couple of weeks, Mountcastle has helped coordinate a team of staff and faculty at Bates, Bowdoin, and Colby colleges who are “printing” visors for face shields that help protect the wearer from hazards including aerosolized coronavirus.

The shields with their 3D-printed visors will be supplied to local first responders, with the Bates-made units and some from Bowdoin to be distributed by the Androscoggin County Emergency Management Agency starting next week.

“We’re very appreciative,” says ACEMA Director Angela Molino, whose agency assists first-response and other service organizations throughout the county, whether local government, nonprofit, or private sector.

Until Bates organized this supply effort, the supply situation at the county level was “dire,” she explains. (Bates has also donated supplies including nitrile gloves to ACEMA, as well as supplies to a local hospital.)

“Locally, PPE resources were not available,” says Molino. “We, along with other county EMAs, requested supplies through the Maine Emergency Management Agency. We have received some items, but supplies are limited globally so sourcing them locally is extremely helpful.” (Bates has since been complemented by the Dingley Press, which, says Molino, donated protective gloves.)

In times of crisis, Mountcastle says, “I think there’s a pervasive narrative that a lot of people tend to respond in selfish ways. But when I look around, I see the opposite — I see just countless examples of people coming together to help one another.

“Once I became aware of all the potential for using 3D printers to create equipment that’s in high need amongst our healthcare professionals and first responders, for me it was a no-brainer. I feel it’s the least I can do to support members of my community and state who need it most.”

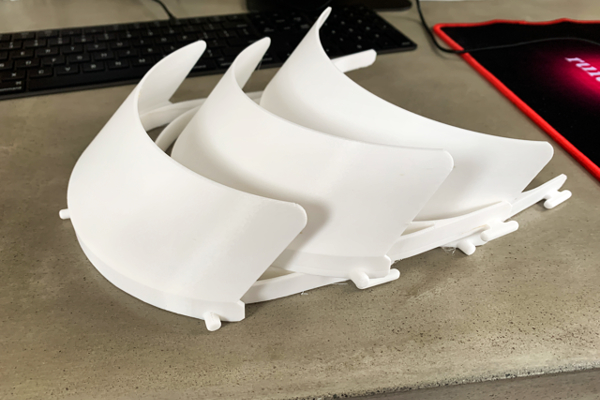

Endorsed by the National Institutes of Health, this particular shield design is remarkably straightforward: Each unit can be made from the 3D-printed visor, an elastic cord or band, and a transparent plastic projection sheet or page protector. “You just punch the transparency with a three-hole puncher and it snaps onto three pins that come out of the visor,” says Mountcastle.

The face shield project is part of a broader Bates effort to help equip folks in the front lines of the COVID-19 fight. During the week of March 23, Bates Facility Services gave 25 cases of hand sanitizer to Central Maine Medical Center. Mountcastle is also looking into 3D-printing parts for facial respirators for CMMC.

This week, the biology, chemistry, and geology departments donated supplies — more than 160 boxes of nitrile gloves, as well as sanitizer and surgical masks — to the ACEMA for distribution.

As for the face shield project, Mountcastle is working at Bates with 3D–printing experts Branden Rush and Cori Hoover, academic technology consultants with Information and Library Services. Each equipped with a printer, Rush and Hoover started making the visors this week.

The larger group includes two people at Bowdoin: Erin Johnson, a professor of art and digital and computational studies, and David Israel, of Academic Technology & Consulting, who has a printer running 24/7. Participating at Colby is Assistant Professor of Biology Joshua Martin. Mountcastle is also reaching out beyond the academic community for 3D-printing capacity.

It was no simple thing to settle on a shield design to produce, says Mountcastle. “It’s a very dynamic scene. New designs are popping up almost every day.” Here, as in so many facets of life these days, “the ground is constantly shifting.”

Designated the “COVID-19 Face Shield,” the open-source design the Maine group is manufacturing was adapted from an existing product by a group led by Design That Matters, a Washington-state firm that designs medical devices for global health in low-resource settings. (The feedstock for the Bates printers is PLA, a biodegradable cornstarch derivative.)

At Bates, 3D printing has been used to make parts for theater department stage sets and create classroom models for the biology and chemistry departments, among other applications. Mountcastle — whose area of research is, broadly, functional morphology and biomechanics, and specifically, mechanisms of insect flight — employs the technology often enough that the departmental printer lives in his lab.

“I’ve used 3D printing, probably, in most of the courses that I’ve taught at Bates,” he says. “It’s a really powerful technique for conducting controlled experiments, because you can design a model and then change one aspect of that model while keeping every other morphological parameter the same.”

For instance, in a winter 2020 course looking at fluid dynamics in sponges, his students designed sponges for testing in a water flume.

“This is an example of how I can put purposeful work into play for myself.”

“With a couple presses of the button, they can double the pore diameter” without changing any other aspect of the sponge. And in his research, Mountcastle often turns to the 3D printer for parts that can’t be bought off the shelf.

A member of a couple of online engineering communities, Mountcastle explains that as COVID-19 spread and the potential for serious PPE shortages became apparent, “engineers and makers around the world started scrambling to design locally manufacturable, low-cost PPE to replace these stocks that were dwindling. There was a lot of activity around this in the online communities that I was part of.”

After determining, first, what type of PPE they could manufacture and second, what design seemed best — simple to make, easy to use and to sterilize after use — the Maine team settled on the Design That Matters configuration. (Universities in Idaho, New York state, Oregon, and Tennessee are among schools that are undertaking similar efforts.)

The face shield project for Mountcastle is, among other things, a timely demonstration of the ideal that drives Bates’ Purposeful Work initiative.

“I’ve spent a lot of time talking to my students about what that means, and encouraging them to think about ways that they can align their personal values and sense of meaning with the work that they do,” he says.

“Now, this is an example of how I can put purposeful work into play for myself. I appreciate having that opportunity, and also to demonstrate that for my students, because it makes that philosophy more real for them. And so I feel very fortunate that I’m able to support members of the community in this way at this time.”