“I’m being overcome with waves of nostalgia, so I can’t do this for too long,” wrote Jane Costlow in response to a recent request to round up photographs of her 26 years of taking Bates students to Russia. “So many amazing and wonderful students and adventures.”

Though today she is the Clark A. Griffith Professor of Environmental Studies, now in her 34th and final year of teaching at Bates, Costlow’s academic training is in Russian literature and culture, and she first traveled in the then–Soviet Union during graduate school in the 1980s.

And since joining the Bates faculty, she has led students to Russia on 10 separate occasions, the first in 1988 and the last in 2014.

+Costlow in Russia

Short Terms: Costlow has led eight Short Terms, beginning in her second year at Bates in 1988, followed by programs in western Russia’s Orel region in 1990, 1996, 1999, 2003, 2006, and 2014. A shorter (two-week) version of the course in 1993 was based in St. Petersburg.

Bates Fall Semesters Abroad: Costlow co-led two Bates fall semesters in St. Petersburg, one in 2000 with Professor Emeritus of Music James Parakilas, and the other with Professor of Politics Áslaug Ásgeirsdóttir in 2009. She also co-led a Fall Semester Abroad in 1997 in Nantes, France, with Professor of French and Francophone Studies Kirk Read.

Costlow poses with her students in 2006 in front of the “coachman’s cottage” on Tolstoy’s estate, Yasnaya Polyana, near Tula. The folk ensemble had just performed. (Courtesy Jane Costlow)

Fascinated by Russian history, culture, politics, people, and language, Costlow cannot imagine her life as a teacher or scholar without those experiences in Russia. “You wouldn’t be a marine biologist and not go to the ocean. [Professor of Geology] Dyk Eusden ’80 does not do geology sitting in his office in Carnegie. If you’re someone who’s interested in another culture that happens to be a living culture, you go there.”

Jane Costlow on why Russia calls to her. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

We recently spoke to Costlow about her experiences teaching and researching in Russia.

Why has teaching in Russia been important to you?

Teaching in Russia allowed me to immerse my students and myself in discovering a place that’s unlike all places— and it’s constantly changing.

True, you can learn a lot about a place that isn’t Lewiston, Maine, when you’re in Lewiston — you can study the history, language, art, and film. The revolution in technology has facilitated that. You can watch the news, you can read today’s papers, and you can read blogs, the equivalent of a kind of Russian Reddit.

But to actually go there and experience it is really diving into the pool. I’ve loved rediscovering the place when you’re introducing it to students. And so in that introduction, in that transaction, you discover new things yourself.

Which is not to say that there aren’t really tough things about going with a bunch of undergraduates to any place, and maybe particular things about Russia. Still, I’ve always loved the informality of teaching while you’re abroad.

Costlow, photographed with a mug of kvas (which is also the word on the barrel) by Peter Olson ’92 during the 1988 Short Term. (Peter Olson’92)

What are the particular difficulties of taking students to Russia?

First, there’s the visa, and with Russia, the application process is complicated. It’s not just a “get your ticket and board the plane” kind of thing.

But beyond that, there’s a sort of paradox of Russian development. On the one hand, it’s a modern, “European” country, although whether or not it’s European has always been one of the central questions of Russian identity. Moscow is enormously well-resourced now and seems not that different, quite frankly, from London or Paris or Berlin.

But once you get outside of Moscow, the levels of development can be quite different, and certainly different from what many, if not most of our students, are used to. Over the years, I felt like I needed to make sure that they understood that there were going to be certain kinds of amenities that they’re used to that they probably were not going to find.

That could include not being able to get the things that they want to eat. And Russians live in tiny little apartments. You discover that you’re in a homestay where it’s a two-room apartment with three generations — and you’re the one who’s gotten the bedroom.

This is no longer the case, but students had to deal with the inaccessibility of ATM machines or public facilities or levels of cleanliness. It’s not France. I felt like I always wanted to be clear to our students about that.

But I’ll also say the students have, by and large, been really game. They’ve been troupers. If anything, the rumors about Russia are far worse than the realities, so I think that there’s probably been a self-selection process for going to a place like Russia. Did I mention negotiating Russian trains?

Jane Costlow, our professor in Moscow, stands on the walkway over the Moscow River near the Kremlin at Zaryad’e Park in June 2018. (David Das)

Tell us about the 1988 visa incident.

Three or four days before we were set to leave for my very first Short Term in the Soviet Union, the packet of passports and visas arrived. All the students’ visas were there — but mine had been denied.

This was 1988, just my second year on the Bates faculty and the first time that I was going back to the Soviet Union after I’d been there as a graduate student. When my visa was denied, I assumed — to the extent that one assumes that there’s actually a reason for any of this — that some bureaucrat didn’t like something in my file. Carl Straub and Jim Carignan ’61 [then dean of the faculty and dean of the college, respectively] contacted Sen. Bill Cohen’s office — he was vice chairman of the Senate Intelligence Committee at the time — and they were able to get me a visa.

I sometimes think that if I hadn’t gotten it, what would have happened? It was the first time I had taken students to Orel, where I would go many times later, and it’s where all of Bates’ Russian teaching assistants have since come from.

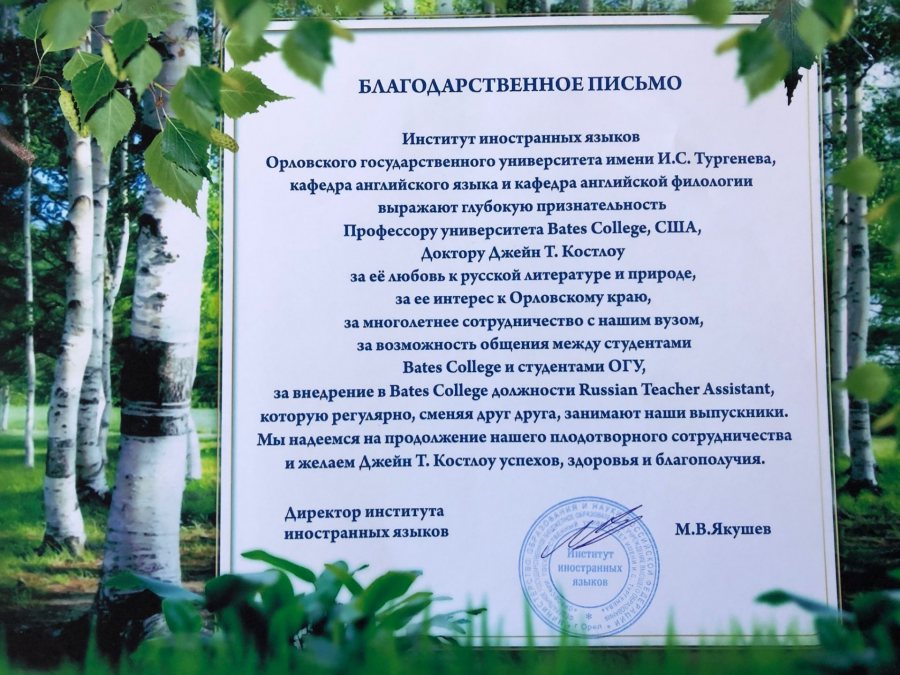

“Letter of Gratitude” from the foreign language department at the Turgenev State University of Orel, which declares its “profound gratitude to Dr. Jane T. Costlow, Professor at Bates College (USA), for her love of Russian literature and nature; her interest in the Orel region; her many years of collaboration with our institution; contact between Bates students and the students of Turgenev State University of Orel which she made possible; and the creation of the position of Russian Teacher Assistant at Bates College, a position which our graduates have occupied regularly, one after the other. We hope for a continuation of our productive cooperation and wish Jane T. Costlow success, health and well-being.”

Why did you choose Orel?

I had visited there and developed friendships there in 1984–85, when I had a fellowship in Leningrad. Orel is a small city south of Moscow in the so-called Black Earth, agricultural part of Russia. And it’s where the Russian writer Ivan Turgenev, who I had written my dissertation on, was from.

In those days, it was quite unusual to get out beyond either Moscow or Leningrad. The Soviets were quite adept at restricting people’s movement beyond the capital cities. But I had asked permission to go to Orel. I found it fascinating. When I was organizing our 1988 trip, the British company helping us said they could arrange for us to go to Orel.

This was the first time I had been back since 1985. Gorbachev was in power, so things were already beginning to change a little bit. It was breathtaking for somebody who had wondered, only three years before, “How are the lives of my friends going to get any better?” In Moscow, you could see that the pictures of Leon Trotsky — for decades considered an enemy of the people — were back up on the wall. Trotsky was back in the Museum of the History of Communism!

But when the people on the street in Moscow who wanted to talk to us heard that I was taking these students to Orel, they looked at me aghast and said, “Oh my God, how can you go to Orel? There’s nothing to eat there!”

Bates students learn to make pelmeni — Russian dumplings that consist of a filling wrapped in thin, unleavened dough — in a restaurant kitchen as part of a cultural program. (Courtesy of Jane Costlow)

Once you arrived, what was the reality like?

There may have been less to eat for some people in Orel than there was in Moscow, and that was part of the Soviet provisioning system. But the hospitality that we received was amazing.

And it started with getting off the train at 4 in the morning and arriving at a motel, where they had tea and cookies and other snacks waiting for us. The people in Orel were extraordinary: thoughtful organization, terrific teachers. And, as my interest became more and more directed towards environmental issues, my relationships with these people became more and more important.

I met Joseph Solomonovich Keselman, an English teacher at the university, who’s still a very dear friend and has taught every single group of students that I’ve taken. And Marina Shimchenok became my on-the-ground contact; she got what I was interested in. She would set up a visit to a dairy farm, or a farm that was in the process of being converted from a collective farm to a privately owned joint-stock operation.

Or we would go to a local national park or a place that made recycled toilet paper. She worked with me over the years as the Short Term became more environmentally focused.

Costlow picnicking in the town of Bolkhov in 1990 with her longtime friend and on-the-ground contact in Orel, Marina Shimchenok, who organized travel for Costlow and her students. (Courtesy Jane Costlow)

What were your goals in taking students to Russia, and how did they change over time as your scholarly focus shifted?

With the exception of 2003, when we traveled to focus more on environmental issues in multiple places, students have always had to take some language no matter what their majors. It was always absolutely key to my understanding of what it means to travel in another country that you at least try to learn a little bit of the language of the country.

My goal for the students is to develop the kind of deeper cultural understanding and growth that you get from being in a place where you’re confronted with living with a family, where you’re humbled by what you don’t know and by the paradoxes and challenging things in other people’s lives.

I’ve always wanted my students to develop friendships with Russians. Maybe that’s still a holdover from the Soviet era of sister-city projects, meeting the so-called enemy, and discovering how much you have in common and what potential that holds for making the world a better place to live.

Did your experiences change significantly after the collapse of the USSR in 1991?

The 1990s were a nightmare economically in Russia, so in 1993, we went to St. Petersburg, which by then had been renamed, with a group of students and only for two weeks, rather than Orel.

That was not a particularly successful trip. The teachers were not as good, and I also think that Russians’ lives were such a mess at that point that it was extremely difficult for them. That was also a period in which there was the sense of criminality. People worried about being endangered on the street, although that was never an issue for us.

And by 2000, you started to see the Putin transformation: people’s apartments were getting better and lives were stabilizing. Public spaces were becoming cleaner. There was the understanding that Putin had delivered some of that.

Was there a particular experience that stands out for you? High or low?

The low point is easy: Short Term 1999, when a student developed acute appendicitis and needed to have an appendectomy.

We were in Orel, and fortunately I had friends who had friends who were able to get us connected to the best surgeon and the best hospital and to get the medication that we needed, because none of that could be taken for granted at that point.

We had great support from Steve Sawyer [then head of the college’s off-campus study office] and from the student’s amazing parents. All’s well that ends well, and she did fine. But I actually had to stay in Russia with her while my husband, David, who was visiting with our two children, took the group to St. Petersburg and got everybody home. I stayed in Orel for the better part of a week until she had mended enough that we could get on the plane.

Post-appendicitis surgery memento: Bates student Erica McIninch poses with her Russian doctor. (Courtesy Jane Costlow)

The high point?

There are so many of them that it’s really hard to say. They mostly involve students’ connections to their peers in Russia.

In 2006, we visited Optina Pustyn, a monastery in one of the great religious cultural centers of Russia. We’d spent the night at a house for pilgrims and then visited a women’s convent that was where Tolstoy’s sister had been a nun. And one of our students, Sami Karmout, a wonderful young man from Palestine who had to travel without a passport, saw a French Orthodox monk he knew from home.

I remember sitting outside the monastery with a group of three or four students after we’d been there for several hours, just kind of wandering around, very quietly, letting the monks go about their daily lives. We talked about what religion meant to us and what our spiritual lives were. It was a conversation made possible by that trip, and I really treasured it.

Sometimes, riding on the bus somewhere, you’d strike up a conversation with somebody over the backseat about politics or philosophy. I have a really wonderful memory of a student talking about how listening to Bruce Springsteen in Russia was helping him understand the backwoods of, kind of, depressed industrial Russia.

Costlow and some of her students, aka The Babushkas, at Optina Pustyn, a monastery that has been enormously important for Russian culture, in 2014. (Courtesy of Jane Costlow)

Things stick in your mind. In 1990 Corey Harris ’91, who’s gone on to an amazing musical career, was on my 1990 Short Term. He struck me as somebody who was an aural learner, and he picked up Russian really quickly. In those days, Soviet citizens could not have foreigners staying at their houses, so we stayed in this little motel on the edge of town.

And as far as Corey was concerned, we were served far too many beets. In Russian, the word for maybe is “mozhet byt.” Corey took to saying “mozhet, beets?” when we sat down to any meal, meaning “maybe we’ll have beets, oh goodie!” And sure enough, there would be beets, and there would be both laughs and groans.

Costlow horseback riding in the Orel region in 2014, at the Zlynskii Stud Farm, a stable that dates back to pre-revolutionary Russia. (Courtesy of Jane Costlow)

You had hoped to take Bates students to Russia this year, for one last time. Even before the pandemic, you chose not to.

It would have been a wonderful way to end my teaching career. It would have been better than Zoom!

I ultimately decided against it because Marina, who had set everything up in the past, died quite unexpectedly two years ago. I had reached out to people in Orel — there’s actually one of our former teaching assistants who’s essentially taken over Marina’s business — and she was game for trying, but I had this feeling that it was probably better just not to do it.

Any study abroad travel that you undertake with students involves a massive amount of work. In my “no longer spring chicken” status, and especially without Marina there, I wondered if I’d be able to pull it off.

Any final thoughts about the study abroad experience?

There has been a deep decline in foreign language study at American colleges and universities. Recognizing that national reality, I hope Bates finds a way to have a serious discussion about its importance and role in a liberal arts education.

On paper, and on balance sheets, these small classes look really expensive. We do not have, and never have had, a language requirement, and I’m not necessarily advocating one. But the study of a foreign language, in my experience and in the experience of many students, is transformational.

Costlow in 2006 with her students in front of the 18th-century Peterhof Palace, home of Peter the Great. (Courtesy of Jane Costlow)

We’re headed into — we are in — rough economic waters. And I don’t know how they’re going to handle that. But the faculty, in terms of being in charge of the curriculum, needs to ask, “What does it mean to be a college that attends to global forces if you don’t train your students seriously to speak a language other than the language that they’re born with?”

But you know, I’m an old language teacher and I would say, “More rather than less” when it comes to the study of language. It’s what I’ve done, and I think I’ve had an impact on people’s lives. I’ve taken probably a couple hundred students to Russia, and it’s really one of the things that I’m most proud of. I certainly hope the college can continue to support that kind of transformative learning.