Different deadly virus. Same great scientific mind.

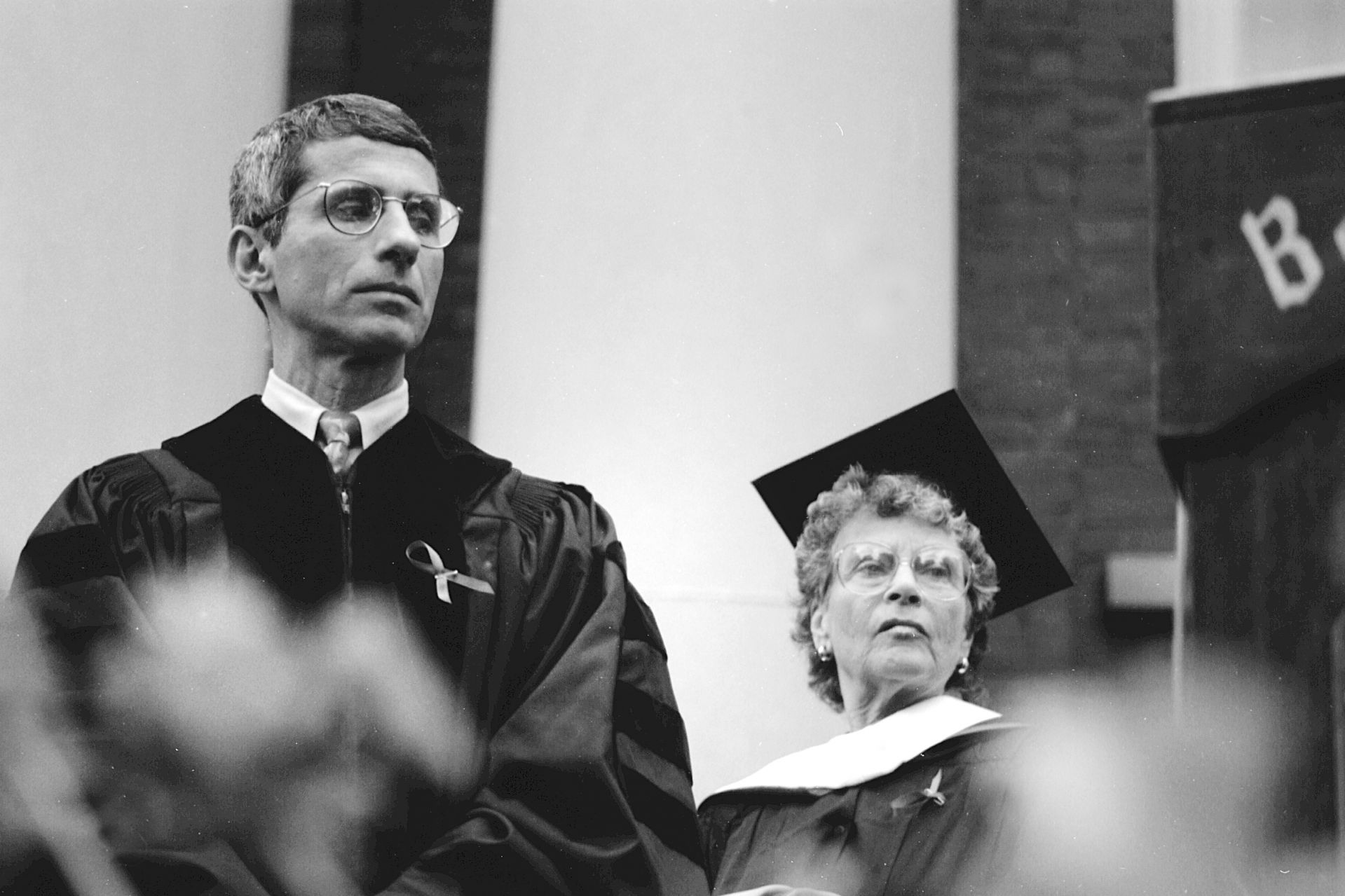

Twenty-seven years ago, Dr. Anthony Fauci, wearing academic regalia with a red awareness ribbon pinned to his gown, stood on the porch of Coram Library on Commencement Day to receive an honorary Doctor of Science degree for his work fighting HIV/AIDs.

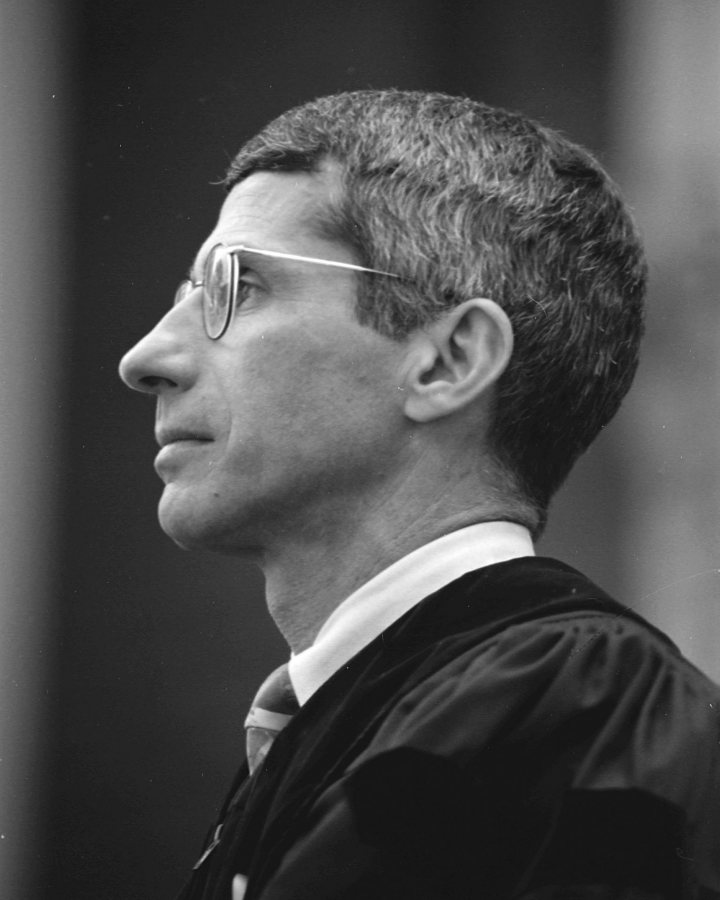

Fauci, today a household name applauded for his steady and smart guidance during the coronavirus pandemic, recalls his 1993 visit warmly. It was, he says, “food for the soul.”

That spring, he says, had been “a pressure cooker,” his time fully taken by HIV science and policy issues in Washington, D.C. Taking a brief break on Memorial Day weekend to spend time on “the beautiful Bates campus” and talking “with really smart and curious students reminded me of the great privilege of having a liberal arts education.”

Dr. Anthony Fauci listens to his Bates honorary degree citation during Commencement on May 31, 1993, as Bates Trustee Jeannette Packard Stewart ’46 stands ready to present his hood. Both are wearing red AIDS-awareness ribbons. (David Wilkinson for Bates College)

As an undergraduate at Holy Cross, Fauci was a classics major who also took premed courses. At Bates, he felt right at home, engaging with Bates students “whose interests spanned these areas and many more — the kinds of well-rounded people who go on to do great things in government, science, the arts, and other professions.”

As Fauci stood on the Coram porch, then-President Donald W. Harward read the degree conferral, which he had written. He said, in part:

“To investigate scientifically is to begin to move from the darkness of ignorance to the illumination of limited understanding. To investigate humanely is to realize that even limited understanding is a gain to be used compassionately.”

+1993 Honorary Degree citation for Dr. Anthony Fauci

Dean of the Faculty Martha Crunkleton presents Fauci:

Mr. President, I am honored to present Anthony S. Fauci, M.D.

In this happy place where the study and practice of science flourishes, we cherish and praise the scientists who help us understand the body and its relation to the world. We welcome this scientist and leader, whose investigations into the immune system contribute to medical research and our health.

Anthony S. Fauci, M.D., the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases at the National Institutes of Health, is the leader of our national effort to understand the human immunodeficiency virus and how it develops into AIDS. With at least one out of every two hundred citizens of this country, and with at least 14 million citizens of the world, now HIV-positive, the virus has spread throughout the world.

In such a global epidemic, the leadership of this scientist helps medical researchers and scientists throughout the world better to understand the complexity of the virus itself and the simplicity of our human need to care for all who are and may become infected.

With his commitment to excellence and his insatiable scientific curiosity formed early by his parents and later by his education at the College of the Holy Cross and Cornell University Medical School, this investigator has studied the effects of infectious diseases on the regulation of the human immune system. He developed cures for three formerly fatal diseases, including Wegener’s granulomatosis and received many national awards in recognition of his work.

His interests in HIV and AIDS developed naturally from this work, and he has been both a leader in the biomedical investigation of the virus and in helping the NIH respond thoughtfully to criticisms from AIDS activists and caregivers that its bureaucracy may be working against the health of persons with HIV and AIDS.

For his remarkable investigations into the nature of the human immune system, for his leadership of biomedical research in infectious disease, and for his work as a government servant in service to the health of this nation and our world, I present Anthony S. Fauci, M.D., for the degree Doctor of Science.

President Donald W. Harward confers the degree:

To investigate scientifically is to begin to move from the darkness of ignorance to the illumination of limited understanding. To investigate humanely is to realize that even limited understanding is a gain to be used compassionately. You, Anthony Fauci, are appreciative of the complexity of our human structure — our frailty as well as our miraculous strength. Through the dedicated efforts of you and your colleagues, you provide scientific and humane leadership in meeting the challenge of our generation: the resolution of the scourge of AIDS.

Therefore, by the authority vested in me by the Board of Trustees, I hereby confer upon you the degree of Doctor of Science, with all of the rights, privileges and responsibilities which here and everywhere pertain to this degree.

Those intertwined qualities, the capacity to investigate scientifically and humanely, had drawn Harward and other Bates leaders toward Fauci as a potential honorary degree candidate.

By the early 1990s, in the position he still holds today, as director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Fauci had already made great contributions to the understanding of HIV and the creation of successful strategies for combating AIDS.

In a recent New Yorker story, staff writer Michael Specter chronicles Fauci’s evolving mindset and approach to HIV/AIDs research through the 1980s.

At first, Fauci’s approach was traditional and “paternalistic,” writes Specter. Though earnestly seeking new treatments and cures, Fauci and the NIAID didn’t readily acknowledge or welcome input from activists and victims, who, among other things, demanded that experimental drugs get into the hands of AIDS sufferers more quickly.

Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases at the National Institutes of Health, greets Rep. Stephen Lynch, D-Mass., with an elbow bump before a House Committee on Oversight and Reform hearing on the coronavirus situation, March 11, 2020, on Capitol Hill. (Joe Gromelski ’74 / Stars and Stripes)

Many scientists, said Fauci, “instead of listening to them, simply withdrew.” But not Fauci, who transformed himself from a conservative bench scientist into, as Specter writes, “a public health activist who happened to work for the federal government.”

“He was the only scientist in the government who was taking HIV/AIDs seriously throughout the Reagan administration,” recalls Martha Crunkleton, who in 1993 was Bates’ dean of the faculty and vice president for academic affairs. It was Crunkleton who wrote Fauci’s honorary degree citation.

“He would listen to all of us who were telling him — in frequently loud, angry ways — to pay attention to so many people dying. He brought the resources of scientific research in the government to bear on the plague.”

In Fauci, Bates could honor someone who was “intentionally addressing robust human challenges” through “engagement that linked academics to civic and community dimensions.”

In doing so, Fauci became the scientist we know today. While respecting that “strict scientific principles…have to be adhered to in medicine,” as he told The New Yorker, he also recognized that “a humanistic touch is needed in dealing with people. You have to combine social aspects, ethical aspects, personal aspects with cold, clean science.”

In Fauci, Donald Harward saw a scientist who exemplified elements of what a Bates education could and should offer in the coming years and decades: more opportunities for undergraduate research, greater engagement between the ivory tower and human communities.

And in Fauci, as Harward recently recalled, Bates could honor someone who was “intentionally addressing robust human challenges” through “research that had its scope broadened to community connections — engagement that linked academics to civic and community dimensions.” (Today, the Center for Community Partnerships, named for Harward and his late wife, Ann, carries out that mission.)

Being able to take a break from HIV policy and science work in Washington, D.C., in 1993 to visit and engage with the Bates community was “food for the soul,” says Dr. Anthony Fauci. (David Wilkinson for Bates College)

In her citation, Crunkleton praised Fauci for helping society clearly understand both “the complexity of the virus itself and the simplicity of our human need to care for all who are and may become infected.”

Her appreciation has only deepened since then. “For five decades, he has shown a deep understanding of the importance of connecting knowledge to action,” she said recently. “Dr. Fauci exemplifies everything Bates, at its best, teaches its students to be and do — fight for truth and the public good.”

Even minus today’s renewed awareness of Fauci’s talents, 1993 would stand as a singular point of pride for the college, says Harward. “Ann and I simply knew that we were recognizing someone who not only incorporated the values of liberal education — and of Bates — but would be, by his work, suggesting the integrity of what we might aspire to be as an institution of learning.”