Sometimes a celebration is just a party, a little event that’s nice but nevertheless removed from the greater scheme of things.

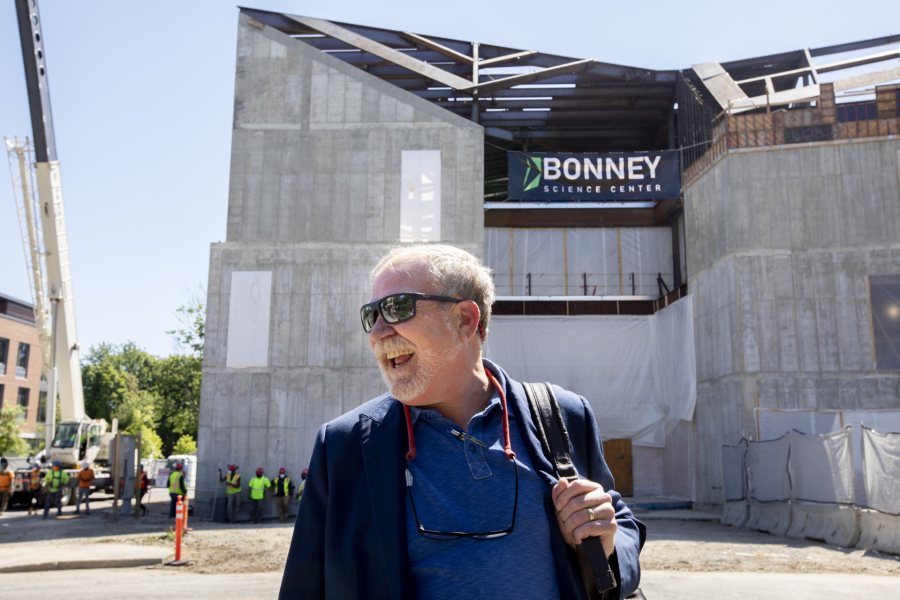

And sometimes it’s more — as in the case of the “topping-off” that brought a few dozen people to the Bonney Science Center construction site on June 16.

Produced by Theophil Syslo with additional video by Michelle Holbrook-Pronovost and H. Jay Burns.

In a typical topping-off, harking back to medieval Scandinavian tradition, an evergreen branch or tree is mounted to the girder (or brick or wooden beam) whose placement will end one chapter in a construction project and begin the next. The idea is to bring good luck to the new building, and maybe some public recognition to the folks involved.

The Bonney topping-off, though, had a symbolic or at least emotional heft out of proportion to the little tree, lent by Facility Services, that was mounted on the girder that would complete the facility’s steel frame. For one thing, it was the first time some participants, including Campus Construction Update, had seen Bates colleagues in the (appropriately covered and distanced) flesh since COVID-19 had descended three months ago.

But the greater scheme of things relating to the event was explicated in remarks by Michael Bonney ’80, who with Alison Grott ’80, his wife, made the lead gift for the science center three years ago.

“It is our sincere hope that for the decades to come, the students and faculty who come through [the science center] include the folks who figure out how to deal with our most vexing problems,” said Michael, who retired from the Bates Board of Trustees in 2019 after 17 years as a trustee and nine years as chair.

He named just three problems, but those were enough: “Climate change. The assault on humanity by viruses, and microbes more broadly. And frankly, because this center is located in this campus and our history, also social justice. Because the kids who come through here will have to go through all these other buildings” — Bonney pointed toward the central campus — “and think about the world differently.”

Against the backdrop of vexing problems, the topping-off itself was a reassuring example of something done not just right but elegantly. After the remarks by Bonney and Bates President Clayton Spencer, the beam was signed by event participants — Spencer and other Bates people, representatives of project management firm Consigli Construction, and folks from architecture firm Payette, which designed the Bonney building.

And then a telescoping-boom Terex crane hoisted the beam to its destiny, a point on the building front over what will be an eye-catching glass-walled stairway.

Crane operator Roger Robbins of American Aerial Services fired up the Terex around 3:21 p.m. At 3:35, steelworker Lisandro Bonilla of Precision Steel concluded the topping-off, to applause, by sliding down a different beam and unfastening the lift line from the new one.

In between, Robbins floated the beam along Campus Avenue toward Bonilla and other steelworkers, who guided it home and snug-tightened bolts to hold it in place. (Torquing the girder to design specs came later.)

In all, pretty neat. “They did two dry runs,” noted Jacob Kendall, Bates construction administrator for the project. We were glad we wore a necktie.

President Spencer had opened the Topping-Off Celebration (a small gathering because of COVID-19 constraints on attendance) with a quick address. “This is an enormous gift and we are so grateful,” she told the Bonneys. “And it is so cool to see it rising out of the ground and now heading toward the sky.”

She said, “If ever there were a time when we actually know we need science, and intensive research, and informed expertise, that would be right now. So the timing of this is impeccable.”

In Vierendeel we truss: The topping-off recognized the completion of the center’s essential construction, and in so doing also marked the halfway point, more or less, of progress at the building site. Construction itself will be done in about a year, but it will take plenty more work to ready the facility for its scheduled August 2021 opening.

Meanwhile, back here in 2020, there’s still a bit of steelwork outstanding — placing some components, completing roof decking, truing up connections and tightening them to specification. “We’d love to just be able to put the very last beam in and say, ‘Hey, that’s it!’ But that’s not how it usually works out,” explains Chris Streifel, the Bates project manager for the Bonney center.

If Tuesday’s celebration was “the formal recognition of the completion of the structure,” he says, “the actual completion of the structure should be next week when the steel effort demobilizes and the concrete crew demobilizes. That will be huge.”

The end of the structural steel and concrete phase, incidentally, activates an invisible but essential function of the Bonney building’s south face. We’ve told you how steel and concrete walls, floors, and load-bearing columns interact to carry the building’s weight down to the foundation and distribute other stresses.

But in the middle of that south wall at ground level is a 50-foot opening that will become a building entrance. That represents a break in the stress-bearing capacity of the wall, compensated now with temporary steel supports in the basement and in that future entrance. And the final steel and concrete placements bring to fruition a surprising load-bearing system centered on the wall itself: Specially supported from both sides and the roof framework, the wall becomes a so-called vierendeel truss.

Named for the Belgian engineer who confounded peers by designing a truss with no diagonal forms, which are what make a truss a truss, the vierendeel concept comprises rectangular forms designed to resist stresses. The rectangles in this case of the Bonney center are…the windows.

“The concrete itself is the vierendeel truss, but it relies on the steel framing, structural slabs, and roof deck for additional strength and stability,” explained Julia Hogroian and Michael Tecci, engineers working on the Bates project for the Massachusetts structural engineering firm Simpson Gumpertz & Herger. In addition, there’s more rebar than usual embedded in the concrete throughout the vierendeel area and especially at the top of the wall.

So what about the last of the structural concrete, for which no one will give speeches, wear neckties, or make champagne toasts? Scheduled for Wednesday, the final placements will top off the science center’s east wall, facing Bardwell Street, along with smaller sections around the fourth-story “penthouse.”

A slump in our reporting: Finally, completion of the exterior walls and roof steel has made even more obvious a defining characteristic of Payette’s design: the prominent use of angles, some shallow and others sharp, across roof and facade. That has necessitated a number of slanting, even downright pointy contours atop the concrete walls.

But if fresh concrete is fluid enough to be pumped through a hose (but not the garden hose, as we learned to our dismay), how do you get it to hold a slope while it cures?

Techniques differ according to need, explained Dan Deschenes, an assistant superintendent and concrete specialist for Consigli. A key tactic is adjusting the “slump,” the viscosity of the concrete mix, by decreasing the proportion of water. Then, for a shallow slope, a mechanical vibrator and other tools are applied to condition and contour the ’crete while it firms up. For a steep slope, the ’crete is held in place with a board or other restraint capping the top of the form.

In other Bonney center news, the application of Blueskin vapor-blocking film began during the week of June 8. In general, this is a sign that a building’s exterior covering-up will soon begin. Sure enough, bricklayers from Maine Masonry arrive next week to set up their impressive Hydro Mobile staging, which goes up and down under its own power, if not by its own free will. Placement of the bricks — which, by the way, are produced from local clay by Morin Brick, across the Androscoggin River in Auburn — will continue through the summer.

Another kind of weather barrier will also show up soon, this time for the roof. While that layer will become part of the permanent roof cladding, it is not the final covering — which we’ll tell you about in a future installment.

Inside the building, from the basement on up, the work of plumbers, electricians, drywall hangers, mechanical engineers, sheet-metal workers, carpenters, and more rolls on. On the third floor, the conclusion of steel placement means that the pace that interior work can shift up a gear or two. Why? Because it’s a four-story building, and the rule is that there must be two floor slabs between flying steel and ongoing work, to protect the workers in case steel is dropped. (You do the math.)

Finally, along with the final steel, chillers and exhaust-air handlers have already been hoisted to the penthouse, where they sit wrapped in protective plastic and awaiting installation.

Can we talk? Campus Construction Update welcomes queries and comments about current, past, future, and imaginary construction at Bates. Write to dhubley@bates.edu, putting “Campus Construction” or “Will someone have to get into the attic to water that poor little tree?” in the subject line.