He’s perhaps the best baseball player in Bates history, yet Harry Lord, Class of 1908, is little-known today, his campus years shrouded in mystery and misinformation.

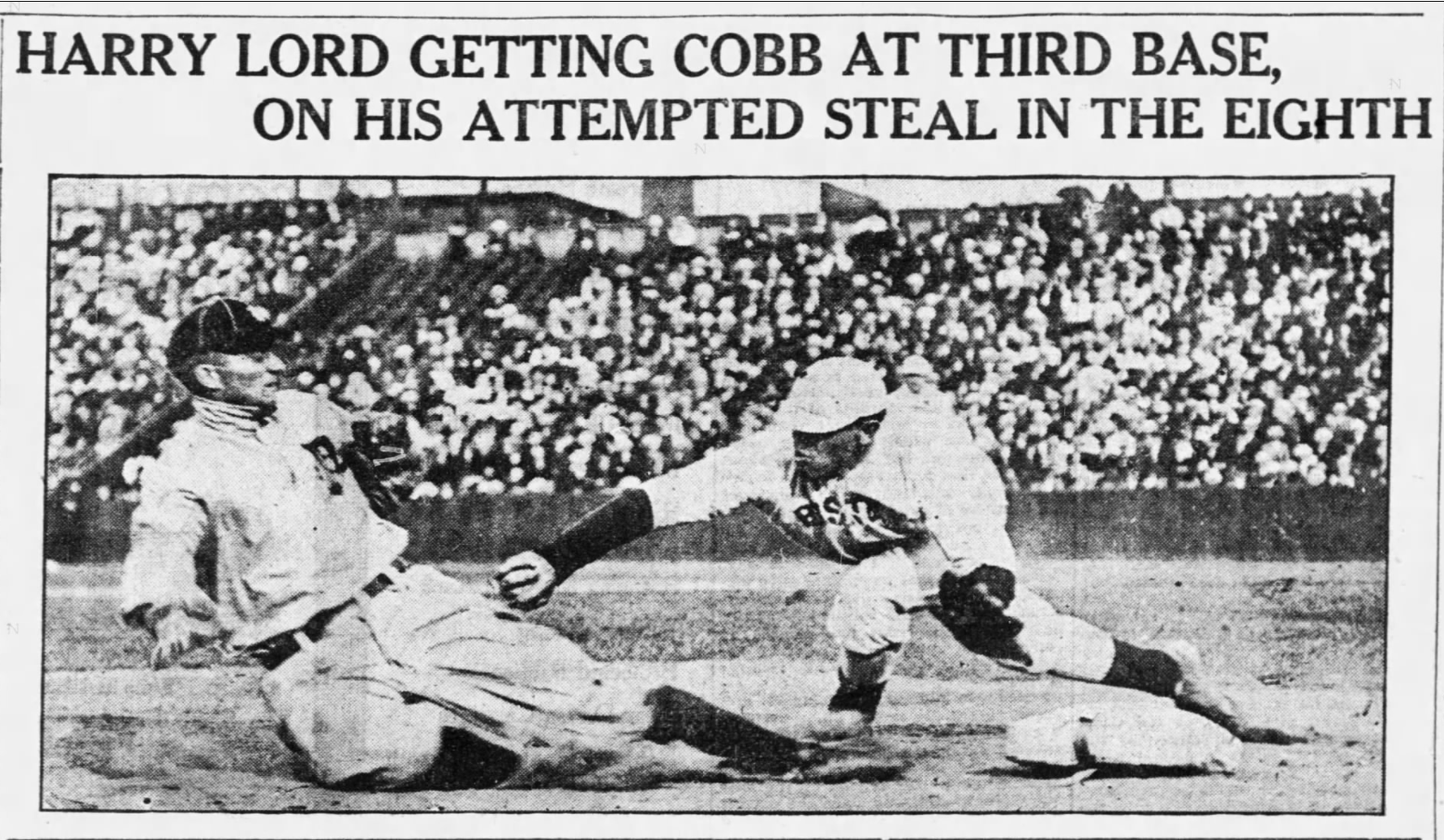

How good a ballplayer was he? As captain of the Boston Red Sox in 1909, he hit .315, good for fourth in the American League behind future Hall of Famers Ty Cobb (who admired Lord’s vim and vigor), Eddie Collins, and Napoleon Lajoie.

As captain of the 1911 Chicago White Sox, he did even better, batting .321. “Lord is acknowledged to be the best third baseman in the circuit,” wrote The English News of Indiana.

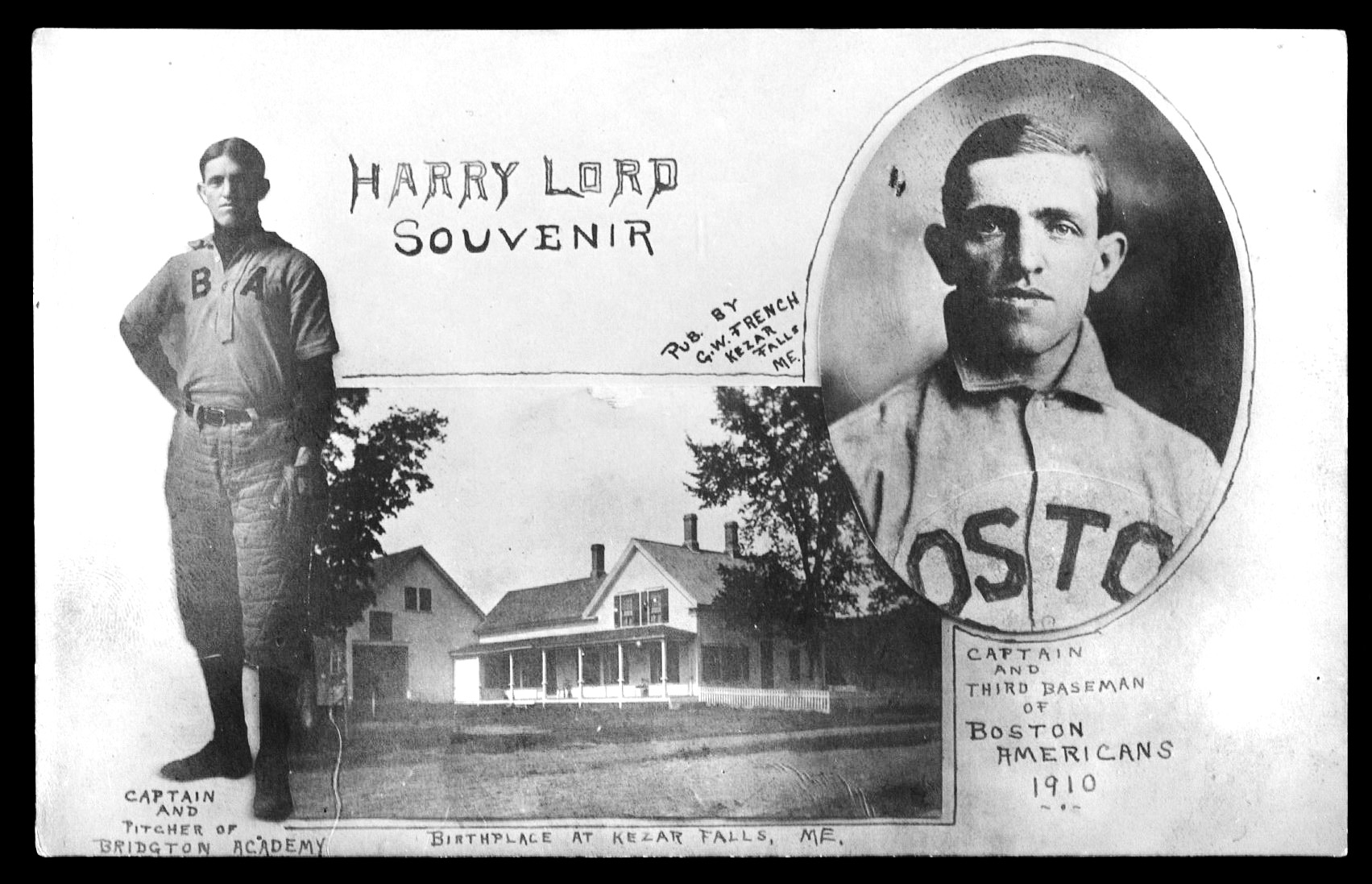

Yet even basic facts about Lord’s time at Bates are often wrongly stated. Wikipedia states Lord “graduated in 1908 and pitched for the baseball team.” The Bates Student in 2014 says much the same. Accounts from his era make similar claims. But he neither pitched, nor graduated.

The truth is complicated. Lord’s story is one of headstrong decisions, Dickensian twists — such as playing for and against Bates in a single season — and loyalty to his team tested by his love for a woman.

Lord was born in 1882 in Kezar Falls, a village in the southwest Maine town of Porter. He attended Bridgton Academy, captaining the baseball team that won a tournament at Bates in spring 1904. That September, along with Bridgton teammate George W. French, also from Kezar Falls, Lord entered Bates as a 22-year-old first-year student.

By tradition, the first big campus event each fall was the freshman-sophomore baseball game. With bragging rights at stake and accompanied by what The Bates Student called the “usual spectacular and noisy demonstration,” the first-years won, 9-3.

Lord led off for the first-years and French batted cleanup. Classmate C.W. Messenger of Bangor — who would also become a major leaguer — batted fifth. Each had one hit in five at-bats. “The freshmen have some promising material,” The Bates Student observed.

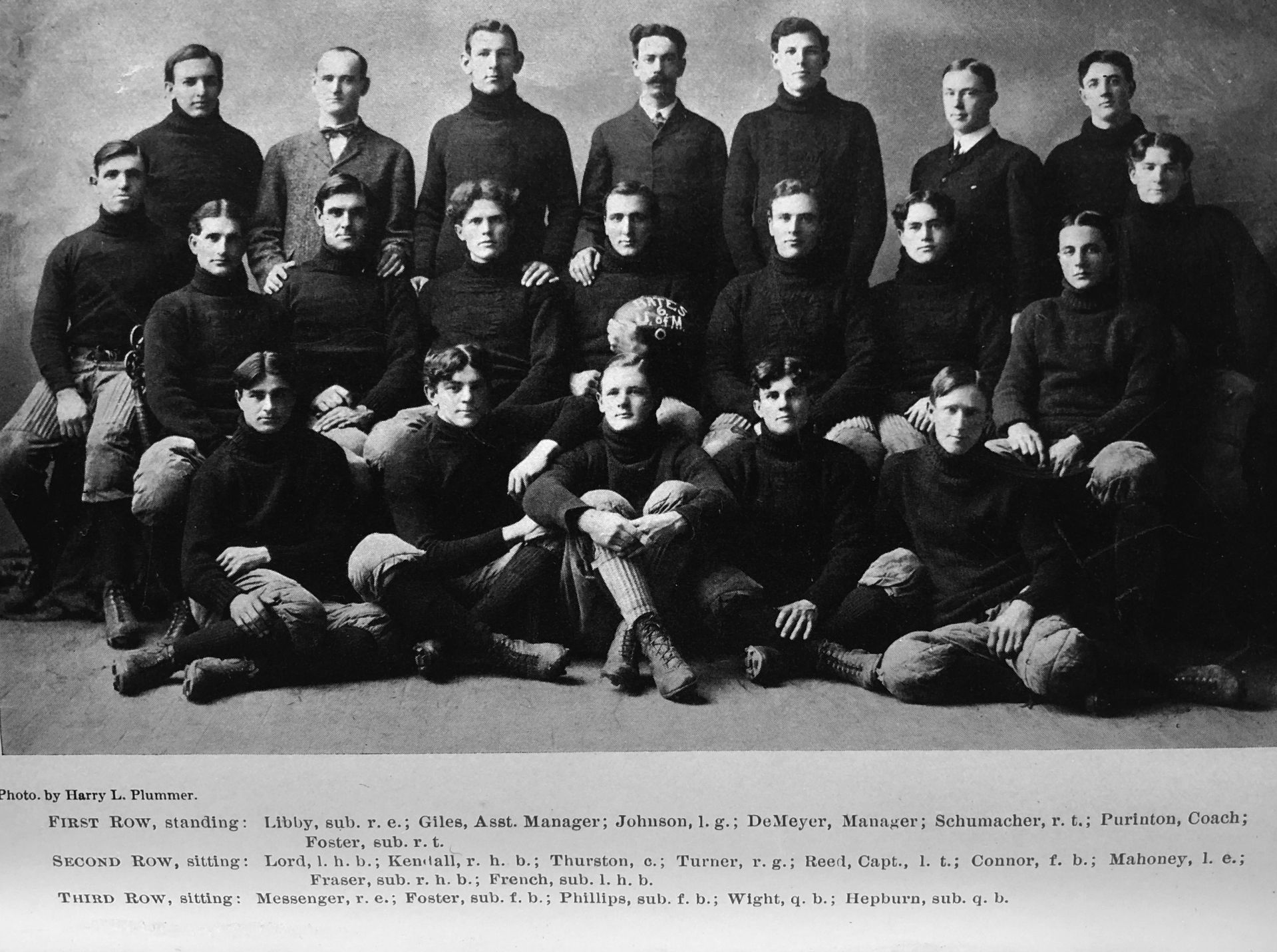

From there, the talented first-year trio turned to football. On Sept. 24, the season opened on Garcelon Field with a 6-0 win over New Hampshire State. On a team of 30, Messenger subbed in at right halfback. Lord and French did not play.

Holy Cross was next. Coming off an 8-2 season, “Holy Cross ranks with Harvard and Yale and is the strongest team that ever came to Maine,” The Lewiston Daily Sun front page declared.

The Crusaders also featured a Maine connection and future Major Leaguer, first-year halfback Bill Carrigan, a Lewiston native who would play 10 seasons for the Red Sox and manage two teams to World Series championships.

But Bates, with 159-pound Lord and 148-pound Messenger starting in the backfield, outrushed heavily favored Holy Cross 125 to 95 yards — but with a costly miscue.

“Had it not been for a fumble by Bates…touchdown undoubtedly would have been scored,” The Boston Globe reported. Messenger was the culprit. The final score was 0-0.

Next up was Harvard, coming off a 9-3 season, including a 23-0 rout of Bates. After Messenger’s fumble, head coach Royce Purinton, Class of 1900, shifted him to left end, making Lord the workhorse in an era when the forward pass was not yet legal.

In a downpour at Soldiers Field, Bates took the opening kickoff and drove for four first downs before Lord fumbled. But Bates held, and drove again. “The whole Bates team was with Lord who was pulled along for six yards,” the Globe wrote.

Eventually, Harvard prevailed 11-0 (at the time, touchdowns and extra points were five and one points, respectively). But Bates, whose heaviest man weighed 188 pounds, earned respect. “Harvard had a heavier line and backs and yet Bates was able to gain at will through Harvard’s line,” the Boston Herald wrote.

Bates reeled off shutout wins against Maine (6-0) and the Pine Tree Athletic Association (40-0), before the much-anticipated Colby game. Special trains to Waterville accommodated the big crowds.

Bates won 23-0, highlighted by two Lord touchdown runs, including one of 80 yards. “Lord had the longest TD run in the game, carrying the ball through the Colby line, hurdling her secondary…then a magnificent run of 80 yards, followed closely but hopelessly by Capt. Pugsley,” the Daily Sun rhapsodized.

“Bates Whales ’Em,” blared the Daily Sun’s front page, though a subhead noted that the game was marred by fisticuffs: “Slugging Used Freely By Both Sides.” Indeed, penalties for slugging — which back then often referred to hitting an opponent during a play, as a dirty way of blocking— were flagged throughout. Lord was ejected late in the game, with French replacing him. Messenger topped off the rout with three extra-point kicks and a fake kickoff recovered by Bates.

The season finale at Bowdoin, with the Maine State Championship at stake, attracted 3,500 fans. Both teams were 2-0 in state play, and spectators ringed the field. Bates took a 6-0 lead, with Messenger kicking the extra point.

But Bowdoin came back with two touchdowns, and led 12-6. With nine minutes left, according to the Lewiston Evening Journal, Messenger shifted from end to halfback, replacing Lord, who left the game. On a crucial third down, with two yards to go for a first down, Messenger was stopped at midfield, resulting in a punt. Bates would have one more possession, but could not move the ball. With the win, triumphant Bowdoin players were carried off the field on the shoulders of fans.

Why did Messenger replace Lord on that crucial third-down play, late in the game? Lord had rushed well all season, and Messenger had been relegated to end. The answer comes in a 1913 Boston Post story that recalls Lord’s playing days. The game is not identified, but likely was the Bates-Bowdoin tilt.

“Some of the strongest men…are to be found in this year’s entering class,” the Student noted. The top-20 list had Messenger at No. 1, French No. 3, and Lord No. 4.

“During one of those fierce clashes that always take place between Maine colleges in the struggle for football supremacy, Harry, one of Bates’ halfbacks, had his leg broken as a result of a savage, flying tackle. This may have been one big reason why he never figured as a candidate for honors on the track (team).”

Bates ended 5-3-1. With such a talented first-year class, the team’s future seemed bright.

![http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/bbc.1467fTitle: [Harry D. Lord, Chicago White Sox, baseball card portrait]Other Title: Card set: Gold Borders (T205)Related Names: American Tobacco Company , sponsorDate Created/Published: 1911.Medium: 1 photomechanical print.Reproduction Number: LC-DIG-bbc-1467f (digital file from original, front) LC-DIG-bbc-1467b (digital file from original, back)Rights Advisory: No known restrictions on publication.Access Advisory: Restricted access: Materials in this collection are extremely fragile and cannot be served.Call Number: LOT 13163-25, no. 125 [P&P]Repository: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/pp.printNotes:Baseball card title devised by Library staff.Issued by: American Tobacco Company.Forms part of: Baseball cards from the Benjamin K. Edwards Collection.Subjects:Lord, Harry (Team member)Chicago White SoxChicagoAmerican Leaguethird basemanFormat:Baseball cards--1910-1920.Photomechanical prints--1910-1920.Collections:Baseball CardsPart of: Baseball cards from the Benjamin K. Edwards CollectionBookmark This Record: https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2008677435/](https://www.bates.edu/news/files/2020/10/Harry_Lord_pnp-bbc-1400-1460-1467fu-scaled.jpg)

That winter, the physical prowess of Messenger, French, and Lord was confirmed during strength workouts. “Some of the strongest men…are to be found in this year’s entering class,” the Student noted. The top-20 list had Messenger at No. 1, French No. 3, and Lord No. 4.

That spring, with the three first-years in the lineup, Bates opened its 1905 baseball season at Garcelon on April 25, walloping Hebron Academy 12-4. Lord, leading off and playing third base, hit a home run and drove in two runs. Messenger, in center field, added three RBIs and two stolen bases. French, in right field, batted ninth.

“Assured that Bates will be represented by a winning team this season. All are in good condition, and the new material is fast,” the Daily Sun noted.

But then something unexpected happened: C.W. Messenger vanished from campus, never to appear again in a Bates uniform. The team stumbled along without him, and by the time Bates faced Maine on Garcelon Field on May 20, the team had just two wins against five losses.

As the Post reported, the Bates “undergraduate body wrathfully bewailed the desertion of the star.”

Then, something unexpected happened again. After the game, another loss for Bates, “Cupid met Harry on the campus after the [Maine] game,” as The Boston Post reported in a 1913 story. “Cupid was accompanied by a young lady whose eyes soon made Harry lose sight of the benefits of a four-year’s course and the crying needs of Bates’ athletic prestige.”

Whether it was the lure of new love or for another reason, Lord, like Messenger a few weeks before, went AWOL. On Memorial Day, Lord missed the game vs. Bowdoin, and Bates lost 11-5 at home. Without Lord the infield was in shambles. “Bates scored more errors than Bowdoin did runs,” the Globe wrote.

On June 7, Lord finally reappeared on a Maine baseball diamond — but now he was playing against Bates and for Portland of the Pine Tree Athletic Association, which was paying him $25 per week. With Bates again making key errors, Portland won 3-1.

Without Messenger and now minus Lord, Bates continued to stumble, finishing at 3-13, its worst record in 21 years (though one of the wins was a dazzling 1-0 victory in 11 innings over Colby and its ace hurler, future major leaguer Jack Coombs).

Lord’s new love was 17-year-old Hazel Hannaford of Cape Elizabeth. As the Post reported, the Bates “undergraduate body wrathfully bewailed the desertion of the star.” And while accounts vary, the couple were likely married by October 1905.

After marrying, Lord tried to settle down, securing a job as a collector in Boston — but he was apparently not happy with the work part of his life. On Christmas Eve 1905, returning by boat to Portland, he happened upon Purinton, his Bates football coach, and vented his frustrations. “Why don’t you try your hand at professional baseball?” suggested Purinton.

Through Purinton’s connections, Lord hooked up with the New Bedford Whalers, an entry in the New England League. He later joined the Worcester Busters, where he batted .280 and led them to a flag.

In September 1907, then with the Providence Grays of the Eastern League, Lord belted a triple during an exhibition game against the major league Boston Americans, who brought Lord up for the last 10 games of the season.

In 1908, the Americans changed their name to the Red Sox, and Lord was a member. Barely a month into the season, “Lord had electrified the entire American League,” the Post wrote.

The Red Sox were dubbed the “Speed Boys,” with Lord the fastest. Lord hit .259 with 145 hits, including 15 doubles, six triples, two homers, and 23 stolen bases, but the Sox finished 14 and a half games behind Detroit.

Lord’s breakout year was 1909. With Tris Speaker joining the Sox, Lord became captain and batted .315, fourth in the AL, scoring 89 runs and stealing 36 bases. On April 21, he stole home in a triple steal against Philadelphia. Still, the Sox finished nine and a half games behind Ty Cobb’s Tigers.

The following year, on July 10 while facing the Washington Senators, Lord was struck on the left hand by a Walter Johnson fastball, breaking a finger. Despite team objections, he left to recuperate in Maine and was benched after his return.

A Cleveland paper wrote Lord was “money mad.” Former teammate Cy Young egged him on: “You’re being given a raw deal, Harry.” Lord demanded a trade and got dealt to the Chicago White Sox on Aug. 9, hitting .297 over the last 44 games of the 1910 season.

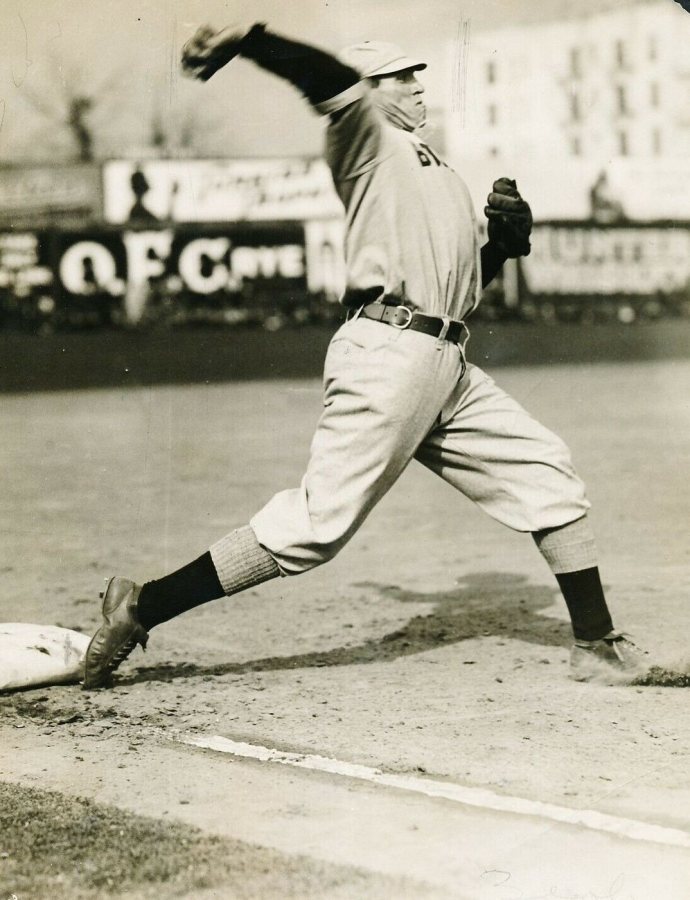

In 1911, as Chicago captain, Lord had perhaps his best season as a major leaguer, hitting .321 with 180 hits, 103 runs scored, and 43 stolen bases. Noting his college experience, The English News called Lord “brainy.”

In Chicago, Lord rejoined his old Bates backfield mate, Charles Walter Messenger. After pulling his vanishing act at Bates in 1905, Messenger had reappeared with Chicago in 1909, and by then was known as “Bobby.” The Chicago Tribune, discovering that the two were “old college chums [who] played together on the football team,” noted that “each says the other was a star player.”

And how fast were Lord and Messenger? In 1911, the latter would win a 100-yard dash, in 11 seconds, against the fastest American League players during a field-day event at White Sox Park.

The former, during an exhibition game in 1910 that included skill contests, was timed from home to first in 3.4 seconds — nearly a second faster than today’s major leaguers. A 1909 Boston Globe story refers to Lord’s speed when describing his dash “nearly to the home plate” to catch a foul popup in 1909.

In his time with Chicago, Lord also settled a score, homering twice off Walter Johnson, the fireballer who had broken Lord’s finger and precipitated his Boston departure. (Johnson is statistically among the most difficult pitchers to homer off in baseball history.)

![Title: [Harry Lord, Chicago AL (baseball)]Creator(s): Harris & Ewing, photographerDate Created/Published: 1913.Medium: 1 negative : glass ; 5 x 7 in. or smallerReproduction Number: LC-DIG-hec-02779 (digital file from original negative)Rights Advisory: No known restrictions on publication. For more information, see Harris & Ewing Photographs - Rights and Restrictions Information(http://www.loc.gov/rr/print/res/140_harr.html)Call Number: LC-H261- 2742 [P&P]Repository: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/pp.printNotes:Original unverified caption data received with the Harris & Ewing Collection: Baseball, Professional, Chicago Players.Corrected title based on research by the Pictorial History Committee, Society for American Baseball Research, 2009.Gift; Harris & Ewing, Inc. 1955.General information about the Harris & Ewing Collection is available at http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/pp.hecTemp. note: Batch one.Format:Glass negatives.Collections:Harris & Ewing CollectionPart of: Harris & Ewing photograph collectionBookmark This Record: https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2016884157/](https://www.bates.edu/news/files/2020/10/Harry-Lord-02700-02779a.jpg)

But Lord’s headstrong — and perhaps hardheaded, too — way of doing things, seen at Bates and in Boston, surfaced again. In 1914, he clashed with White Sox owner Charles Comiskey over salary and with manager Nixey Callahan over signals. After 21 games, the 32-year-old demanded, and got, his release.

Out of baseball, he had free time. In June, the Student wrote that “Harry Lord of the Chicago White Sox” would appear in the first ever Alumni Parade at Reunion.

Over the next three years, Lord served as player-manager with Buffalo Blues of the “outlaw” Federal League. He also played for Lowell, Mass., in the New England League, for Gardiner, Maine, in a semi-pro league, and for Portland of the Eastern League.

In 1918, Lord intersected with Bates again. With Purinton serving in France during World War I with the YMCA, Lord stepped in as baseball coach. “Harry Lord Arrives!” the Daily Sun declared on April 22. He coached Bates to a 4-4 record in a war-shortened season.

As for C.W. “Bobby” Messenger, he was out of the big leagues by 1914. Ever the mysterious figure, little is known of his life. He died in 1951, age 67, in Bath, Maine.

As for their classmate George French, he actually graduated from Bates. French served as the official Maine state photographer from 1936 to 1955, winning more than 200 awards, including a medal from the Photographic Salon in Tokyo. All his prints and negatives reside today in the Maine State Archives.

French died in 1970, age 87, having said that “I hope to leave a monument to a life devoted to picturing the beautiful side of the great outdoors.”

Out of professional baseball after nine years, Harry Lord finally did settle down, entering the grocery and coal business in Portland. He became a Mason, joined the Rotary Club, coached at South Portland High School, and served on the South Portland school board and in the Maine House of Representatives as a Republican.

In 1948, Lord died at age 66 and was buried in Kezar Falls. Lord’s wife, Hazel, survived him and herself went on to serve three terms in the Maine Legislature. She died in 1974. Also surviving were a son, Harry Jr., and daughter Corrine, Bates Class of 1927.

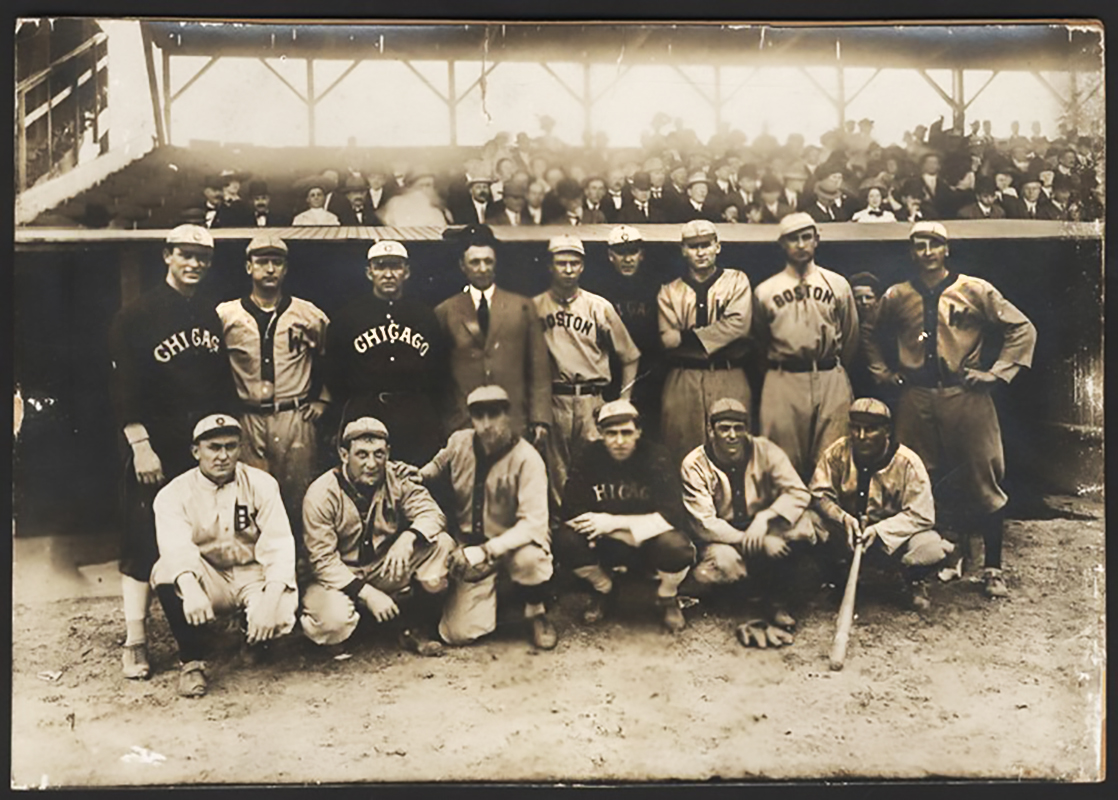

In 2018, after the death of Lord’s grandson, a team photograph of Lord, Cobb, Johnson, Speaker, and others, taken at an unofficial 1910 all-star game at Shibe Park in Philadelphia, went to auction. The vintage photo sold for $6,063.

In photographs, Lord’s jutting jaw is prominent, a physical signal of a competitive nature that marked his career — regardless of Lord’s team. In his later years, the old White Sox captain expressed a regret born of a competitor, that he wasn’t there to stop his Sox from throwing the infamous 1919 World Series.

“Joe Jackson and Buck Weaver and the others would have listened to me,” Lord said. “I could have stopped it if I’d had to punch the ringleader in the nose.”

Bob Muldoon ’81 lives in Boston. The author of the novel Brass Bonanza Plays Again, he was a guest on the Bates Bobcast in July.