“I was struggling,” admitted Loral O’Hara.

The NASA astronaut was explaining, via Zoom, to a class of Bates sophomores what they were seeing on her shared screen: a video of O’Hara wearing a huge spacesuit, fumbling around underwater in a large pool, aka NASA’s Neutral Buoyancy Laboratory in Houston, Texas.

To paraphrase the famous Apollo saying, O’Hara had a problem: Her safety tether had gotten tangled in some tools right in front of her.

The tether is needed so “you don’t accidentally become disconnected and float off into space,” she explained. “It’s really important” (yes, astronauts still excel at understatement). Untangling it with hands wearing huge astronaut gloves is “like trying to use oven mitts to untie a knot.”

At the time, O’Hara was chagrined. But she now knows that it was OK to flub a task when the consequences were low. “I could have made that mistake in orbit someday when the consequences are much higher. Being able to make a mistake, fix it, and laugh about it and learn from it — that’s a really important skill, not just for spacewalks, but also for life.”

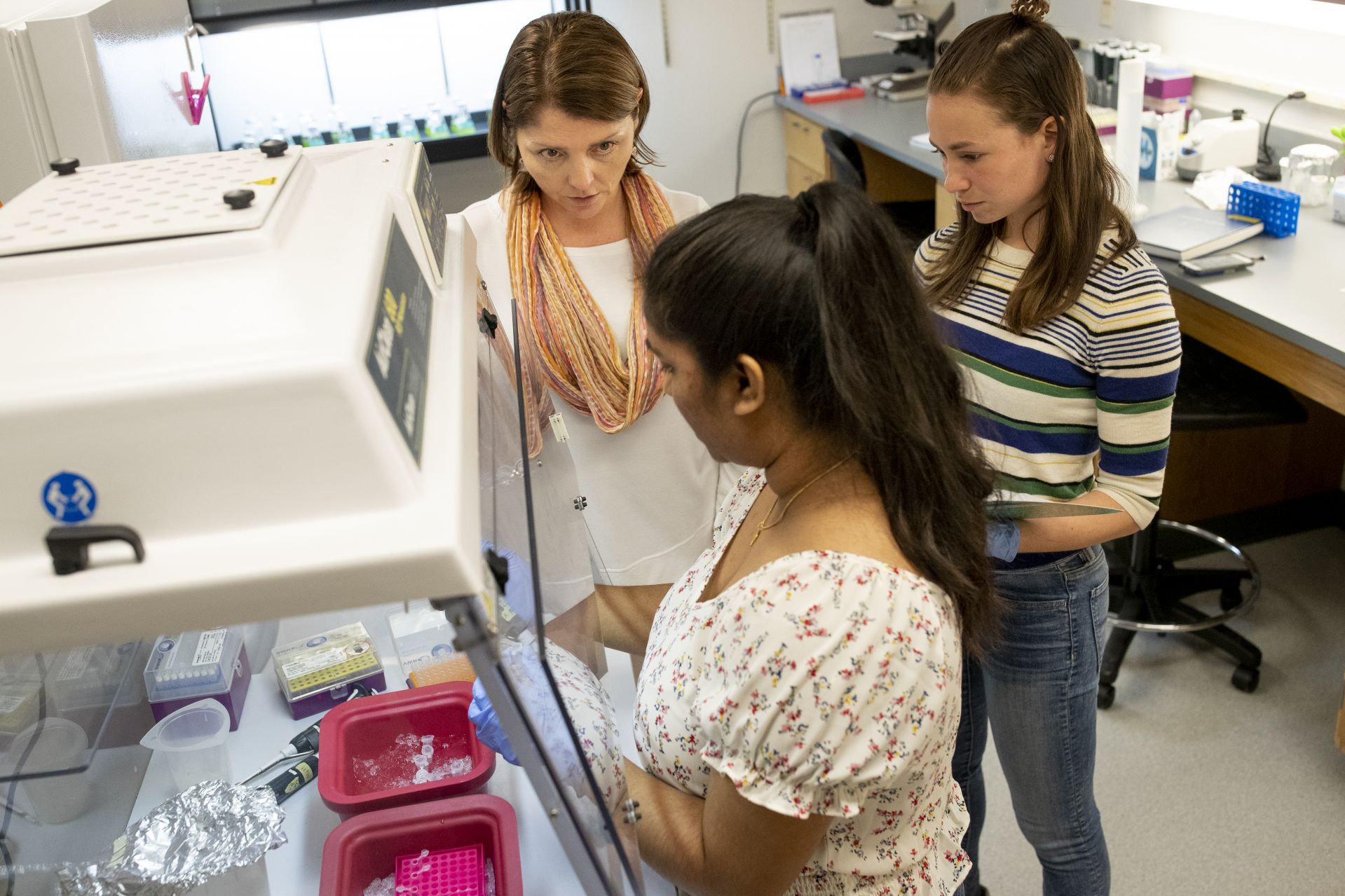

It was just the sort of message that Associate Professor of Biology Larissa Williams and Assistant Professor of Biology Lori Banks wanted their students, a cohort of impressionable sophomores on the cusp of becoming science majors, to hear.

These sophomore are STEM Scholars, in the second of a two-year academic program that helps incoming students who are interested in STEM majors begin to think like young scientists, problem-solve like young scientists, and, most of all, believe in themselves as young scientists.

The program is part of a Bates effort to disrupt an old mindset about what it takes to succeed in majors related to science, technology, engineering, and mathematics, known as STEM.

The mindset, entrenched in U.S. higher education for generations, says that having the right stuff for STEM means that you survive while others fail. Indeed, introductory STEM courses are often known as just that: “weed-out” courses.

And while weeding out might be valuable in gardening, finding a great NFL quarterback, or naming the winner of a TV reality show, it’s now understood that weeding out in STEM courses only proves the shortcomings of the teaching model, not the student.

At Bates, that’s changing.

“We don’t believe that certain people can do STEM and certain people can’t,” says April Hill, the Wagener Family Professor of Equity and Inclusion in STEM. “If you are accepted to Bates College, we believe that you are fully capable of not just getting a STEM degree, but thriving along the way.”

STEM Scholars take a year-long First-Year Seminar, then a year-long course sophomore year. This fall’s sophomore course had 30 students, taught in two sections by Williams and Banks. This fall’s first-year STEM seminar was taught by Aleksander Diamond-Stanic (physics and astronomy) and Katy Ott (mathematics).

Instead of a divide and conquer approach, the STEM Scholars program focuses on support and community building. The STEM Scholars “is not meant to be a competitive community,” says Hill. “It’s where you can learn and thrive together while building your science skills.”

While the primary goal of the program is to better serve the demographic of students who, data show, have frequently suffered negative STEM outcomes at Bates and nationally — Black students, Latinx students, first-generation students — “we also have STEM Scholars who have other reasons to be part of a community that is interested in supporting each other,” says Hill.

To that end, O’Hara was asked by Edgar Sarceno ‘23, a prospective math and physics major from Santa Fe, N.M., for advise on how to overcome coursework challenges. Lean on your community, O’Hara said, such as group study sessions.

She also suggested a visualization strategy: Think about past successes to bolster confidence in meeting a current challenge. “When I get to a really hard task, I think back to when I struggled and succeeded.”

Hill meets with many of the 28 “alumni” STEM Scholars who are now juniors and seniors, talking with them about STEM and, to help the program achieve sustainability, helping them train to be mentors to the program’s first- and second-year students.

“I’ve gotten the most joy in the last two weeks, talking to these students. It’s hard for all our students” — required masks, physical distancing, and limited social and other activities — “but they’re finding their own way to thrive. They’re studying like crazy — and feeling really proud of what they’ve accomplished in these courses.”

During the Zoom session, O’Hara did a fine job at meeting the sophomores where they are, on the verge of deeper STEM study. In a happy coincidence, her stories echoed themes of the college’s Purposeful Work program, particularly how one’s satisfaction and success in what we pursue must be aligned with what feels purposeful.

“Pay attention to what you really enjoy,” O’Hara said, “what you find most fun and exciting, as well as actively seeking new and different experiences.”

Banks says she often talks to students about what feels purposeful to them — about “being aware of what your own personality is telling you, what skill sets you’re developing, what things you’re drawn to — and how you might be able to best serve the world, the community, your school, whatever, just by being you.”

This fall, O’Hara was one of 10 scholars, researchers, and other professionals that Banks, Williams, and other professors brought into their STEM Scholar classrooms.

“The speakers contributed to many of our course goals,” explains Williams, such as bolstering students’ confidence and enthusiasm in science and math, and having a growth mindset. “Loral spoke explicitly to this,” said Williams.

O’Hara, who Zoomed in from Star City, the earthbound home of the Russian space program, traced her path from her childhood in Houston to becoming an astronaut based in Russia, where she continues her training until her chance to blast off on a mission to the International Space Station.

Long gone are the Apollo days when being an astronaut meant you were either a commander or a pilot.

O’Hara’s 13-member class of astronauts includes a Navy submarine warfare engineer; a microbiologist who studies organisms in subsurface environments, such as caves and deep-sea sediments; an emergency room physician; a commander of a Navy flight test squadron; a medical surgeon and combat helicopter pilot; and a SpaceX engineer with unusual prior experience: as an ice driller in Antarctica and commercial fisherman in Alaska.

“It’s a huge diversity of backgrounds,” O’Hara says. “This is one of my favorite things about the astronaut office: It shows that there’s no one path to success.” The diversity of the astronaut class also underscores another goal of the course, says Williams, “that the best science and math is done by diverse teams.”

Recalling her own path, O’Hara shared how, as a child, she loved to explore, hiking in the woods and mountains. Eventually it led her to latch onto the idea of being an astronaut (growing up in Houston also helped foment the idea).

“I wrote a letter to NASA, and they wrote me back and told me to follow my dreams and study a STEM field,” O’Hara said.

After earning a bachelor’s degree in aerospace engineering at the University of Kansas and a master’s in aeronautics and astronautics from Purdue, she did deep-ocean engineering and operations work at Woods Hole (Mass.) Oceanographic Institution, including experiences with the famed human-occupied vehicle Alvin and the remotely operated vehicle Jason.

O’Hara, who became friends with Williams while at Woods Hole, was selected to NASA’s astronaut training program in August 2017.

Careers can have a tidy and linear appearance when we look back, O’Hara says. Sitting in Star City, where she is now eligible for a mission assignment, it might seem “easy to connect the dots and see how the pieces of your life come together.”

But she assured Williams’ students that when you’re 18 and looking ahead, it’s not always clear how things will fall into place. “That was definitely the case for me,” she said.

“If you had asked me in high school, if I would be working on deep-ocean research vessels by my 30s, I probably would’ve given you a sideways glance and asked, ‘What’s a research vessel?’”

The message resonated with Mariam Josyula ‘23 of Longboat Key, Fla.

“It’s inspiring to talk with people who come from different backgrounds and taken different paths, but have still become so successful. You have to work hard and persevere, but your dreams are possible.”