Seeking to improve the efficiency of its beer making, a Lewiston craft brewery partnered with a Bates student who is not yet old enough to legally sip suds in Maine.

Emily Tamkin ’23, a 19-year-old biology major from Lafayette, Calif., used her Purposeful Work internship at Baxter Brewing Co. to help the brewery measure the bitterness of its ales and lagers. Not with a sip and swallow, but more accurately, with a high-tech Bates laboratory instrument.

Bitterness is key to making any beer taste the way it does, and it’s usually created by adding more or less hops. An India pale ale is made with more hops, hence its bitterness. Pale ales and lagers are made with less hopes — they’re smoother.

Smaller craft breweries like Baxter typically use commercial software to measure a beer’s bitterness, which is expressed in International Bitterness Units, or IBUs. Every beer has an IBU “target.” Baxter’s flagship Stowaway IPA is a 69, while the brewery’s Staycation Land Brilliant Lager is 17.5.

For some time, Baxter Director of Quality Merritt Waldron has suspected that his IBU software has been telling him to add “too many hops to get to our target values” for each Baxter beer. This is where Bates and Tamkin entered the scene. Working with Waldron, Tamkin analyzed Baxter beer samples in the Bates lab of Assistant Professor of Biology Lori Banks.

A physics graduate of the University of Southern Maine, Waldron is the author of Quality Labs for Small Brewers. As Baxter’s quality czar, he brings a scientist’s curiosity to his work. But to investigate his theory, he needed research support, including access to a spectrophotometer to calculate IBU levels experimentally and the controlled environment of a laboratory. So he reached out to Bates, “our neighbors.”

Science, whether chemistry, biology, or physics, is as integral to beer-making as barley, hops, and yeast, so the fact that Tamkin isn’t old enough to drink Baxter beer (she turns 21, Maine’s legal drinking age, next August) is irrelevant, says Waldron. “Emily and I just talk about the science.”

In Tamkin’s project, the science is found in the chemistry of hops. Hops contain alpha acids, which when heated become bitter-tasting iso-alpha acids. “When these acids hit your taste buds, your brain receptors understand it as bitter,” Tamkin explains.

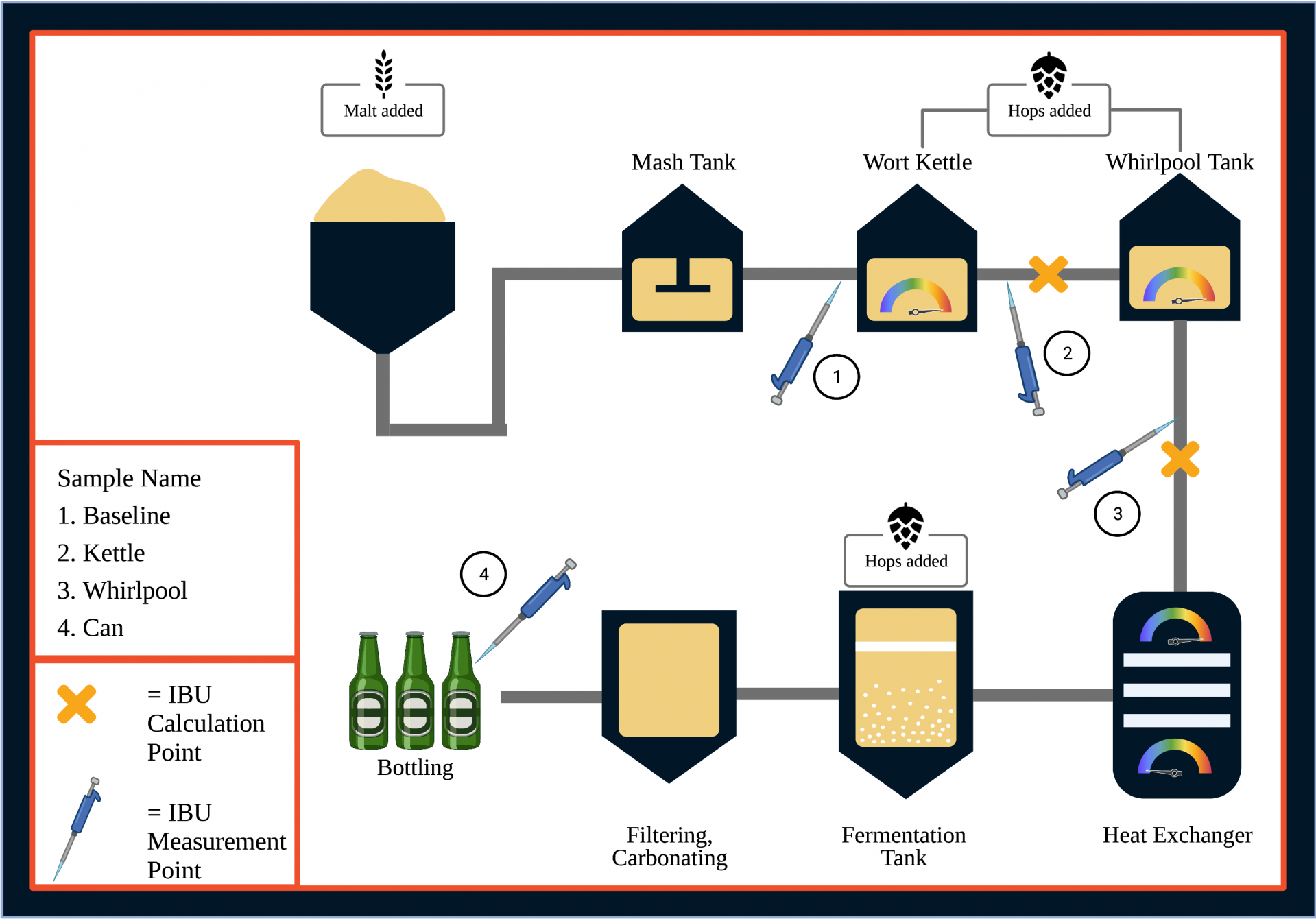

Over the summer, Tamkin would drive downtown to pick up samples from the brewery, located in stunningly renovated Bates Mill space. The samples are taken at four spots in the brewing process, including before hops are added and the final canned product.

She then drove the samples back to the Banks lab in Carnegie Science Hall, soon to be moved to the new Bonney Science Center. (Lest she get pulled over for possession of alcohol, Tamkin had a letter from Waldron indicating that she was transporting beer for research purposes.)

On a recent Wednesday, she picked up samples of Stowaway; Hopeful, a session IPA; and Gopher It, a hazy triple IPA. In the lab, she used a spectrophotometer to calculate the true IBU values of various Baxter beers by measuring their iso-alpha acids. All told, Tamkin analyzed 12 of the brewery’s nearly 20 beers over the summer.

Tamkin is now back home in California and will present her findings after the Bates school year starts.

For Baxter, the partnership with Bates is about brewing excellent beer while spending less on ingredients like hops. We asked Waldron a question: What if Tamkin does find that Baxter can lower the amount of hops to achieve an accurate IBU target? Won’t lowering the amount of hops change the taste of the brewery’s beers?

Not necessarily, he says. “Most human palates can only taste a small range of IBU values. Most can’t taste the difference between 10 IBUs. So if Emily’s results say that I can shave off 10 IBUs to achieve a more accurate number, we can lower the amount of hops, save money, and the consumer won’t notice the difference.”

Hops are pricey, up to $20 per pound, so the savings could be significant. Waldron runs the numbers for Stowaway IPA, which uses a popular hop known as Cascade, which runs about $10 per pound.

“Five pounds of Cascade is equal to about 10 IBUs in one ‘turn’ of Stowaway IPA,” — about 30 barrels — “and we typically brew 280 turns of Stowaway a year,” Waldron explains. “If I can save five pounds of Cascade per turn, that’s 1,400 pounds of hops per year. At around $10 per pound, that’s an annual savings of $14,000.”

Tracking IBUs is just one part of the Baxter quality program. There’s also a sensory program, anchored by a beer-testing panel of Baxter employees, that rigorously identifies the essential nature of each Baxter beer, through taste, smell, look, feel, and, yes, sound.

“We call the essence of each brand its ‘true-to-target’ profile,” says Waldron. “Testing brews against their profile is the goal of the sensory program.” Any reduction in hops suggested by Tamkin’s research would need to make its way through the beer-testing panel, he says.

For Tamkin, the summer project sweetened an interest in food science. “I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about a career, and grappling with whether that meant pre-med or academia,” she explains.

Turns out, a third path appeared in Tamkin’s search for purposeful work. “Working with Baxter, being able to do all this amazing science with them, has opened up a world for me — how science relates to other industries that I never really thought of before.” And that’s the point of Purposeful Work internships, explains Banks, for how they “empower students to take on real-world problems while pursuing their studies.”

Besides helping Baxter, Tamkin hopes her experimental results will yield solid enough findings for a scholarly paper.

“The experience of being able to design a research project and do it well enough to write a paper about it has been really, really exciting,” she says. “I wouldn’t have had the opportunity without Baxter being so great and without the Banks Lab.”

Waldron studied physics at the University of Southern Maine. At the time, “I didn’t really know what I was going to do with my major,” he says. “Then I ended up getting into brewing. Seeing all the science behind it, I just got super excited about it.

“So, as a scientist myself, being able to inspire a real-world application of the theoretical stuff you learn in college in someone like Emily — that’s part of the reason why I was really excited to have a Purposeful Work intern, not to mention being able to partner with Bates, our neighbors.”

So raise your can of Baxter Stowaway, your Gopher It, or your Staycation Land, and say cheers to good science, good beer, and good neighbors.