Billions in box office sales tell a Hollywood tale: Movies about Black and white buddies teaming up to defeat bad guys have been a crowd favorite since the 1940s.

Whether it’s Richard Pryor and Gene Wilder foiling kidnappers in Silver Streak, or Eddie Murphy and Nick Nolte taking down a depraved killer in 48 Hrs., the experience of watching interracial buddy films — “good guys overturning the bad ones” — gives us pleasure, says Charles Nero, Benjamin E. Mays Professor of Rhetoric, Film, and Screen Studies.

Audiences expect to see, and man do they get, rousing displays of “manliness, cooperation, love, and affection between males,” however chaste and non-sexual. In these films, like In the Heat of the Night, Philadelphia, and Men in Black, eradicating evil, whether racism, homophobia, or aliens from outer space, is simple, Nero says. “As simple as black and white men becoming friends.”

Of course, that’s not just simplistic, but “a lie,” says Nero.

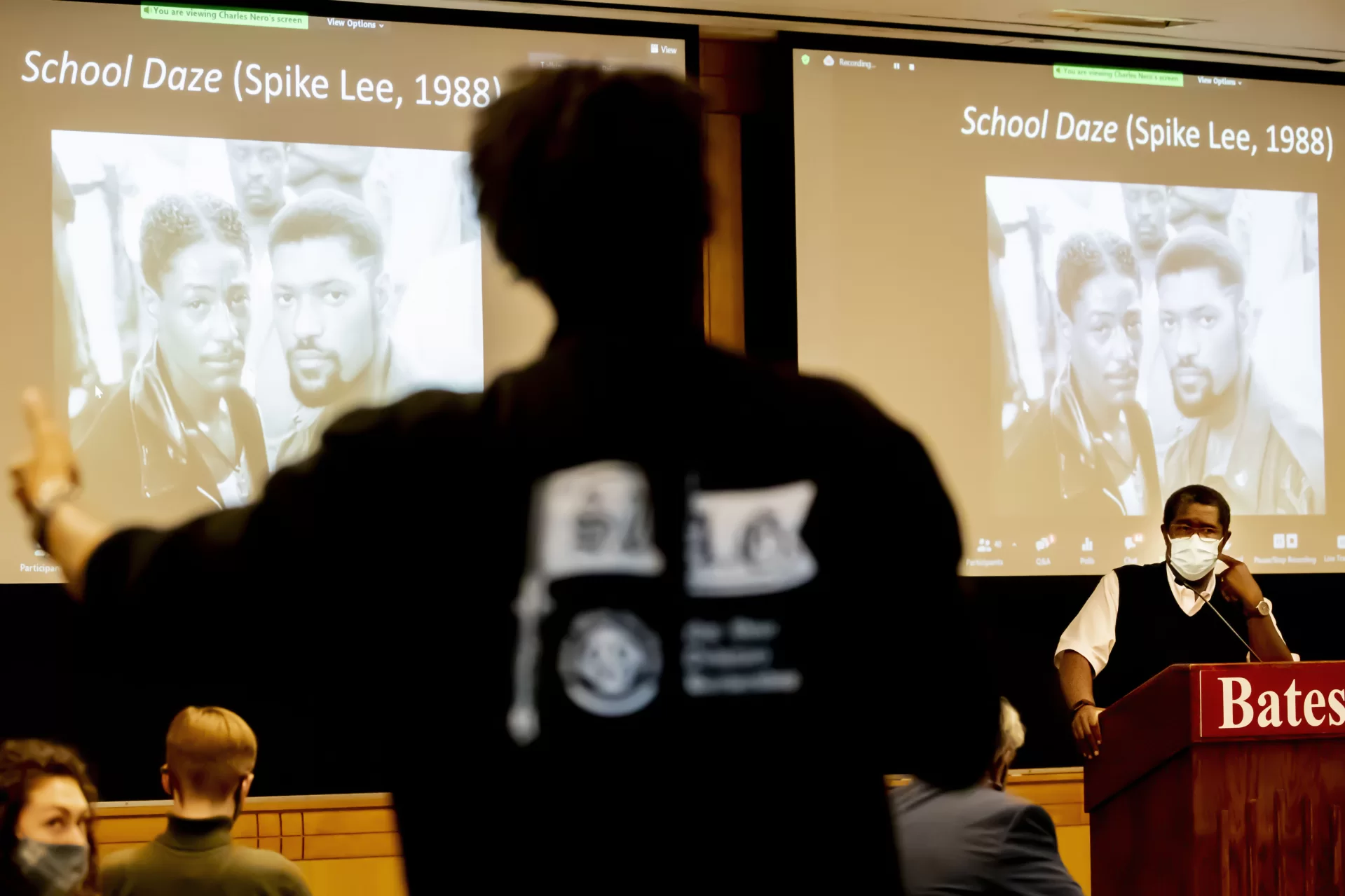

The recipient of the 2021 Kroepsch Award for Excellence in Teaching, Nero delivered his wide-ranging insights into the popularity and problems of interracial buddy films during a recent Bates talk, culminating with an analysis of why Spike Lee’s 2018 BlacKkKlansman is an “awesome and subversive takedown” of the genre.

Established in 1985, the Kroepsch Award honors faculty for their performance in teaching. A member of the Bates faculty since 1991, Nero specializes in film, literary, and cultural studies. He is the longtime chair of the college’s Martin Luther King, Jr. Day Committee and a member of the Africana program.

Held in Keck classroom and streamed live via Zoom on Sept. 27, Nero’s Kroepsch Lecture drew Zoom questions from several of Nero’s alumni students, including one from Nero’s earliest years as a Bates professor.

Forget the “fierce urgency of now”: Hollywood was telling Black Americans to just wait.

The interracial buddy film dates to the Cold War after World War II. Hollywood had joined the fight against the perceived Red peril, in the film lot through blacklists and on the screen, producing movies with anti-Communist themes.

The first few, such as 1949’s Home of the Brave and 1951’s The Steel Helmet and Bright Victory introduced a familiar trope, the “multiracial, multifaith, and multi-ethnic troupe of American soldiers who bond with each other to combat and defeat a Communist enemy.”

A pivotal moment occurs in Steel Helmet when a Communist North Korean army officer (Harold Fong) asks the Black soldier (James Edward) why he’s loyal to racist, Jim Crow America.

“The response Edwards gives is one about patience,” Nero explains. “The African American soldier professes loyalty to an American exceptionalism. America as a nation will eventually abandon its white supremacy and become a welcoming place for him. The African American man just has to be patient because America is destined to become better.”

With interracial buddy films, Hollywood discovered a way to “secure Black American loyalty in the fight against Communist appeals to people of color in the U.S. and abroad,” explains Nero. Forget the “fierce urgency of now”: Hollywood was telling Black Americans to just wait.

With that message, Hollywood had laid the groundwork for a new genre.

In Stanley Kramer’s The Defiant Ones, Sidney Poitier and Tony Curtis received Academy Award nominations for their roles as convicts on the lam, chained together. “Initially they hate each other — Curtis’ character was a working-class racist,” Nero explains. “But since the two were chained together, they have to work together to evade capture, as the movie endlessly shows us.”

The messages sent by The Defiant Ones and subsequent interracial buddy films are both simplistic and untrue because they reduce racism and white supremacy to something “one-dimensional, an internal state,” explains Nero, when we know that racism and white supremacy are institutional and systemic, not internal.

Which brings us to Spike Lee’s BlacKkKlansman, based on the true story of a Black police officer in Colorado Springs, Colo., who sets out to infiltrate the Ku Klux Klan in the 1970s, helped out by a white undercover officer.

“It has the appearance of an interracial buddy film,” says Nero, but instead, Lee delivers an “awesome takedown” of the genre. One tipoff that this isn’t your father’s interracial buddy film is a scene showing KKK members watching and cheering D.W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation.

Birth of a Nation suggests that interracial friendship (between a Northern abolitionist and his mixed-race protege) will create a national catastrophe that only the Ku Klux Klan can solve.

By including the scene, Lee is “exposing the lie about interracial friendship in the national narrative. Birth of a Nation’s message about interracial friendship — that it will create catastrophe — is a lie just as the buddy film’s message, that interracial friendship is a “godsend that will end racism and white supremacy,” is a lie.

Though Lee forewarns viewers that lies are afoot and that he’s out to disrupt a familiar genre, BlacKkKlansman seems to “end” in the familiar way. “Black and white men as friends. They can all sit down as friends and enjoy a beer. All is right in the world. The wicked have been punished. Order is restored.”

But no, it’s not over.

Using one of his cinematic trademarks, the double-dolly shot, Lee creates a “surreal moment,” in which two Black characters, Ron Stallworth and Patrice Dumas, with guns drawn, seem to float down a hallway and into the future. They see a cross is burning. The KKK is still around. There’s a rally, real scenes of the 2017 Unite the Right white supremacist rally in Charlottesville, Va., reminding us of the endless cycle of racism.

Their passage down the hallway “evokes the image of the Door of No Return, from which enslaved Black people left the European fortresses of West Africa for America,” Nero says.

It’s an “exhilarating moment of cinematic realism” as director Lee “stamps the Black experience onto the interracial buddy film. In this Black experience, Lee evokes capture and Middle Passage, enslavement and white supremacy in America, as a never-ending cycle.”

Oh gosh! Adam!” Nero exclaimed, clearly pleased. “That’s great.”

During the post-talk Q&A, one question came from Adam Gaynor ’96, a student of Nero’s from, as he said with a chuckle, “the last century.”

“Oh gosh! Adam!” Nero exclaimed, clearly pleased, after hearing that Gaynor had asked a question. “That’s great.”

Gaynor asked Nero his thoughts about why the film would have the character Flip Zimmerman be Jewish when in real life the white cop was not Jewish.

Without going into Spike Lee’s motivations, Nero noted that Zimmerman being a Jew makes his entry into the KKK more interesting. Zimmerman “is passing,” Nero said. “He and Ron have a conversation about what it means to be Jewish. Ron has to think about his own identity.”

Asked about his interest in watching Nero’s talk, Gaynor said, “I wouldn’t miss an opportunity to listen to Charles lecture — he’s one of a kind.”

Gaynor has spent most of his career in education, and is now a founding partner of Plan A Advisors, a consulting firm for nonprofits. He earned his doctorate from New York University in education and Jewish studies. Speaking from that breadth of experience, Gaynor calls Nero “an educator, scholar, and mentor par excellence.”

At Bates, Gaynor was deeply involved in confronting anti-Semitism, homophobia, and white supremacy. “Bates and Maine were anything but welcoming to students of color and Jewish and LGBTQ students,” he recalls.

“A core group of faculty of color, including Charles, invested time and energy in mentoring vulnerable students, ultimately helping Bates to retain many of us.”

Gaynor recalls taking Nero’s course “Sexuality in the Era of AIDS.” The course’s “extremely challenging material” demanded that students step “far outside of our comfort zones,” Gaynor recalls.

Nero was there every step of the way, including taking students on an overnight, off-campus retreat, where he facilitated exercises and discussions, “punctuated by family-style meals and activities.”

The experience “enabled students to know one another more deeply and to feel more comfortable engaging with the material through trust and vulnerability. It completely transformed the class dynamic for the remainder of the semester.”

And when it comes to engaging with a film, Nero says it’s possible to watch our favorite films, whether BlacKkKlansman or a more typical interracial film like Shawshank Redemption, with a critical eye and without having to push aside feelings of pleasure.

Watching with a critical eye means asking ourselves questions about our pleasures: Why do we enjoy the things we do? Why do interracial buddy films perfectly scratch that itch for so many of us?

“Film is a solicitor of pleasure,” Nero says. “One of my jobs, as an educator, and I take it very seriously, is I want to encourage us, not to reject pleasure, because, you know, I’m a queer person, and I was told that that was just wrong. So, I don’t want you to reject pleasure, I want you to ask questions about your pleasures.”

And one of the questions we can ask is about the racial implications and dynamics of the movies we enjoy so much.

“I think the question is, do we ask ourselves, ‘How does something like race play out in what I find pleasurable in what I’m going to enjoy?’” Nero said. “Too often, we don’t have those moments to interrogate.”