Dana Hall’s future users are scheduled to begin moving into the building starting this coming Monday, Aug. 15.

The move is one of the final milestones in a comprehensive renovation that was years in the planning and about 14 months in execution. The academic building formerly known as Dana Chemistry Hall will open as fall semester classes start on Sept. 7.

Built in 1965 as a center for chemistry teaching and research, Dana exits the renovation with a broadened mission: It’s now the home of introductory education in biology and chemistry at Bates, but also houses state-of-the-art general classrooms for use by all academic departments.

The repurposing is part of a greater transformation of science facilities at the college that has also included construction of the Bonney Science Center, which opened nearly a year ago.

In addition to redefining Dana’s academic role, the makeover vastly improves the experience of simply being inside this building at the heart of campus. Once known for a confined and confusing interior layout, Dana now boasts bright, open interior spaces and vastly improved wayfinding.

Credit there goes to the Boston architectural firm Payette, which also designed the Bonney Science Center. And the two buildings now share a bold visual style distinguished by a white, gray, and lime-green palette, clear sightlines, and a certain sense of industrial chic.

The college received a municipal certificate of occupancy for Dana in June, and Bates and project construction management firm Consigli Construction have formally agreed that the project is “substantially complete” — meaning that operational control has reverted to the college.

While the list of folks to be based in Dana is still in flux, a few are confirmed: Bruno Salazar-Perea, a lecturer in biology and the faculty fellow for medical studies; Alyson Farrington, assistant in instruction in chemistry and biochemistry; and staff from the Environmental Health and Safety office and from the Center for Inclusive Teaching and Learning.

Two or three days should suffice for moving people in, Bates Project Manager Chris Streifel said in an Aug. 3 interview. As for inanimate objects, virtually all furniture is on site, if not all in its allotted locations. And supplies and implements for scientific work? “Alyson has tons of stuff for the general chemistry labs” coming in from the Bonney Center, Streifel said.

“That’s far and away the biggest single cluster of things. Then there’s a mishmash of stuff coming from Carnegie Science Hall for the biology spaces. The move is really not a big effort, at least compared to moving into Bonney last summer.”

But Streifel also noted that tangled supply chains continue to affect the Dana project, if not in a decisive way. “There’s an autoclave that we’ve been waiting on for months that still has an unknown delivery date. We’re seeing slowdowns in some other science equipment that we ordered quite a while ago.”

He added, “The furniture that we ordered with ample lead time, well, it certainly came down to the wire in a couple of cases. But there’s nothing still [missing] at this point that should waylay us from opening for classes.”

As for work on the building itself, the chore list had gotten pretty short when we visited Dana last week. A substantial number of doors still awaited installation, a process slowed by a shortage of workers in that particular trade. (Our suggestion of hanging beaded curtains as a stopgap measure was politely rebuffed.) There was painting to finish as well.

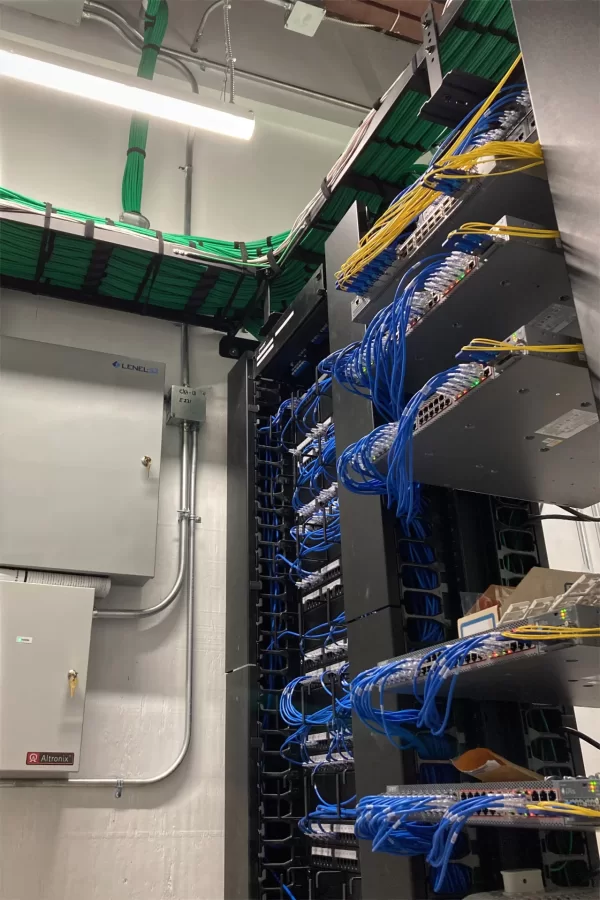

In terms of mechanical, electrical, and plumbing systems, the building-wide tests collectively known as commissioning are wrapping up, Streifel said. Scheduled for late last week was the integrated systems test, which focuses on things electrical. “We’ll turn everything off and turn it on and see if it comes back the way it’s supposed to.”

Punch lists are being closed out, meaning that remaining defects are being addressed. Last Friday, the project team was slated to review that process one last time with Payette principal architect Michael Hinchcliffe.

Six years into the relationship between Bates and Payette, Streifel characterized the Boston firm as “fantastic” — expert, engaged, and supportive. “When there’s a need for something, they’re there to provide it,” he said. “They’ve put together a good building for us” — again.

“This space is going to work really well for us for many decades to come.”

When slabs collide

Deep in the renovation zone on Chase Hall’s first floor, Bates project manager Kristi Mynhier points overhead.

In a part of the building where demolition has left little but structural elements, removal of the suspended ceiling has revealed two very different surfaces.

With a massive steel beam at their junction, each surface is the underside of a concrete floor slab. One slab comprises long, pale panels of concrete. But the concrete substance of the other can’t be seen from here: It’s atop a dark complex of steel parts and a layer of paper.

We’re visiting an area where, as part of the 14-month renovation of the Bates landmark, a pair of restrooms will be built. This is along the junction of the two additions to the century-old original building: Memorial Commons, opened in 1950, and a 1978 expansion of the dining area that resulted in what came to be known as the Small Room (or the Tool Shed, a snarky allusion to the more studious undergrads who were rumored to gather there).

It’s slightly poignant to consider that the restroom will be used by people who, unless they closely follow Campus Construction Update, have no idea of the history over their heads.

As part of the 1950 renovation, the paper-lined slab was cast in place atop tubular steel joists, explains Consigli Construction’s Michael Carpentier, project superintendent for the Dana and Chase renovations. (Consigli is the construction management firm for both renovation projects.)

While the exact process isn’t known, it’s possible that the paper was used to constrain oozing around removable wooden forms that actually supported the concrete as it cured. Similar techniques were used in Dana and Pettigrew halls.

The 1978 slab, meanwhile, “is a panelized precast system set over steel beams,” Carpentier says. “These panels were fabricated offsite and craned into position before installing the roof structure.”

Such discoveries exemplify the archaeological appeal of building renovations — especially when the building is as old as Chase, built in 1919.

Both Consigli and Canal 5 Studio, architectural designers of the renovation, are doing what Mynhier calls a “phenomenal job” harmonizing the project goals with campus affection for Chase — and with the sometimes-challenging realities of a building with a mind-bending history of makeovers large and small.

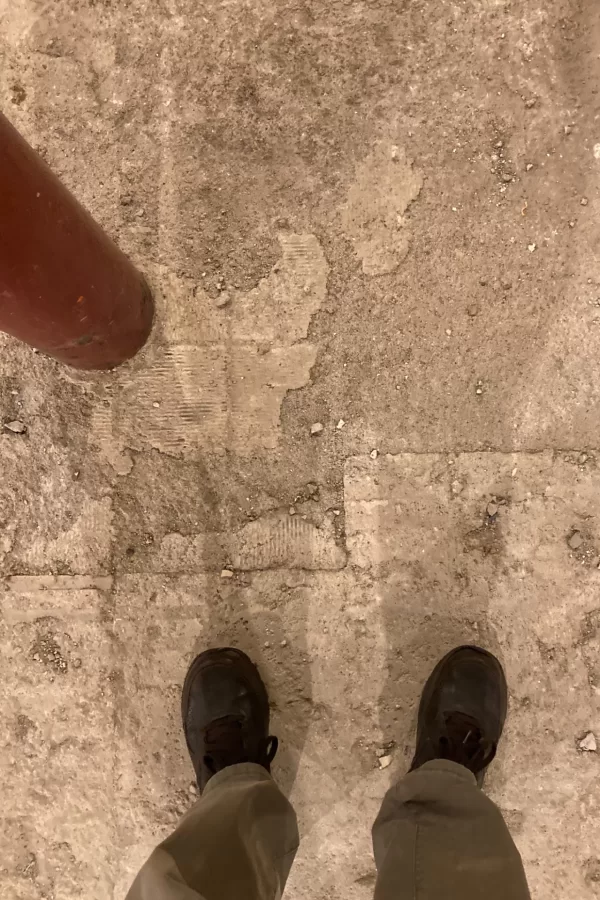

If surprises come with every building project, Chase Hall is especially rich in “What the…?!” moments. The junction between the two additions, for instance, poses its own puzzle for the project team to solve — but it’s underfoot, not overhead.

As Mynhier says, “We have got the flooring contractor working to see what we can do, as far as prep goes, so that we can successfully install new flooring” over the joint between the additions’ subfloors, a groove that zigzags across the space.

Continuing the surprise theme, we told you last time about a bunch of them clustered in a section of Chase’s second floor that’s laid out in rooms — most recently, Student Affairs offices — branching from a central corridor.

One such surprise was the presence within two walls of load-bearing columns where the building plans showed no such thing. The walls will be removed as planned, rendering three smaller rooms into one flexible student-activities room, but the structurally necessary columns will stay, joined by a few new ones.

“We’re reworking the furniture plan around the columns,” says Mynhier.

In other Chase news, hazmat-abatement firm Acadia Contractors continues to remove asbestos-bearing materials at specific sites in the basement and on the first floor. Abatement on the latter has included a big chunk of Chase Hall Lounge and a section of ceiling near the door that opens into the Carnegie Science–Chase Hall courtyard.

The later assignment entailed the removal of both materials hazardous and otherwise. “Instead of having two different trades mobilize, we just had Acadia perform selective demolition to get to where they needed to abate,” Mynhier explains. The ceiling job will make way for a new layout of walls, stairs, and access to Campus Avenue — taken together, a defining outcome of the renovation.

But Chase, of course, has two entrances onto Campus Avenue, and both will be dramatically reconfigured in the renovation. At the entrance near Bardwell Street and the Muskie Archives, visitors will find a new elevator and stairs designed to streamline access to the Office of Intercultural Education and other key facilities at that end of the building.

In preparation for those new features, the demolition of large expanses of floor slab on three levels began late last week. Consigli is knocking out the sections of slab.

Mano a Mondo

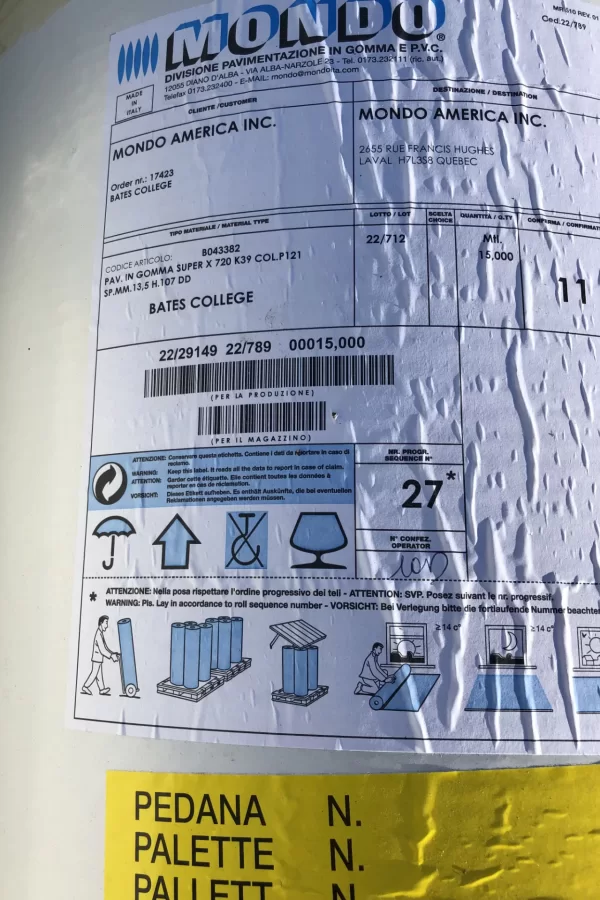

The new Mondo rubber surface on Bates’ Russell Street Track should all be in place early next week.

Then the surface has to rest for 30 days, allowing sunlight to cook off a paraffin coating from manufacturing, before it can be striped. That paintwork, using a proprietary product made by the track-surface manufacturer, will be the final step in the project. The paint dries to the touch in as few as 10 minutes and as many as 30, depending on weather, but needs up to three days before it’s ready for use.

The Mondo Sportflex Super X 720, a two-layer product produced by the same Italian firm that supplied the track’s original surface 21 years ago, was delivered on July 25 by eight tractor-trailer rigs, and installation began the following day.

While Bates’ varsity track and field teams won’t use the facility till spring, there’s still time pressure on the resurfacing project, from the soccer program, whose first home games take place Sept. 10 with both men and women playing Bowdoin. Because the soccer pitch sits inside the track, players will have to walk across the track for the games, and the Mondo installation needs to be done by then.

In the meantime, notes Bates Project Manager Paul Farnsworth, he and project contractor Miller Sports Construction of West Chester, Pa., worked with Facility Services to program the soccer field irrigation system so the track would be dry where subcontractor Wicked Flooring of Rockford, Ill. (an Illinois company with a New England name!) needed to lay Mondo each day. (Watered every other night, the grass field is divided into 16 irrigation zones that the system cycles through.)

We explained previously that gluing the Mondo into place is about as hands-on as a job can be: It’s done by one man wielding a hand tool. But it turns out that much of the Mondo work has required the armstrong method.

The rolls were unspooled and positioned by hand, stretched around the curves by hand, and their edges trimmed and joined by hand — again, by a single worker with a hand tool.

On a day when our colleague Jay Burns, Bates Communications editorial director, was photographing progress at the track, the Wicked Flooring cutter-trimmer was Corey Ernst. Burns learned that all told, Ernst would make more than a mile of trims, changing the blade in his knife every 30 feet.

He asked Ernst if he gets into a flow, in the psychological sense. “Yeah,” Ernst said. “You kinda have to, if you’re going to do this work.”

As the 50-foot strips are unrolled and placed side by side, workers slightly overlap the sections to allow for expansion in their width. Then Ernst comes through, trimming the overlaps. After the surface is glued in place, the seams are weighted down with blocks.

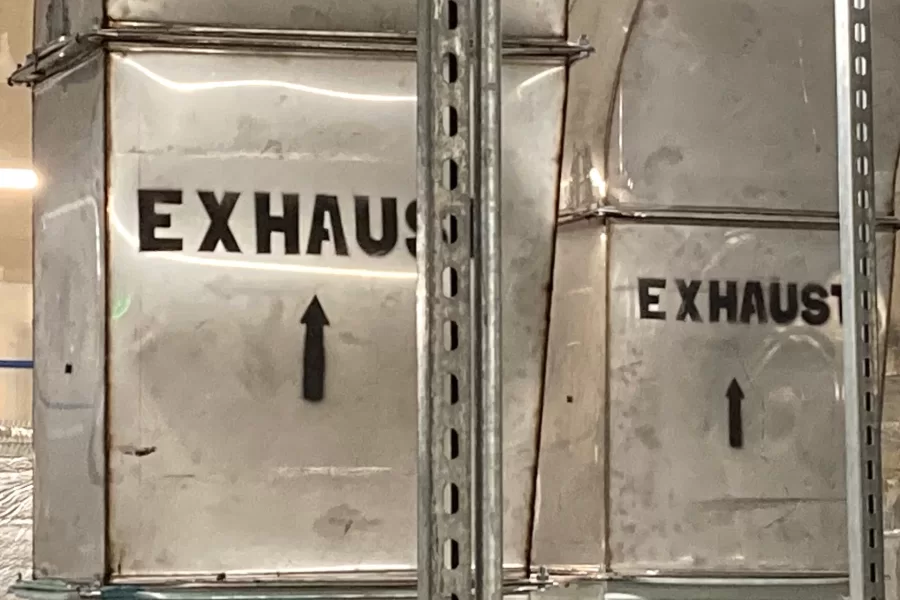

Elsewhere on Farnsworth’s summer chore list, the upgrade of the heating, ventilating, and air conditioning system at the Olin Arts Center is progressing. In the Bates College Museum of Art, new in-wall insulation has been placed and new air diffusers and related piping installed above the ceilings.

Still to be delivered are central chillers and an air handler for the HVAC system. In the meantime, rental HVAC equipment will both enable technicians to balance flows within the revamped air-handling network and keep building occupants comfortable.

This being August, a few projects on Farnsworth’s list are wrapping up. The new bleachers at the Campus Avenue Field are nearly finished. And the plumbing upgrades in Page Hall are complete. These included not just the replacement of the original 1957 toilets with water-conserving 21st-century models, but the substitution of water-bottle fillers for the porcelain drinking fountains on each floor — which, Farnsworth quips, “came over on the Mayflower.”

Can we talk? Campus Construction Update welcomes queries and comments about current, past, future, and parallel-universe construction at Bates. Write to dhubley@bates.edu, putting “Campus Construction” or “While the autoclave is delayed, couldn’t they clave manually?” in the subject line.