On April 12, 1971, one day after Easter Sunday, a 23-year-old Brazilian artist in residence at Bates showed one of his newest works to a gathering of fellow artists: a strikingly tall wood sculpture depicting Jesus Christ on the cross.

Fifty-two years later, with this month being an important time for many faiths, including the Christian Holy Week, we brought the sculpture out into the bright springtime light at Lake Andrews for a closer look.

We also sought insight about the art and artist from two Bates people with different perspectives: a Bates alumnus from Brazil who was at that April 1971 event in Chase Hall, and the Rev. Dr. Brittany Longsdorf, the college’s multifaith chaplain.

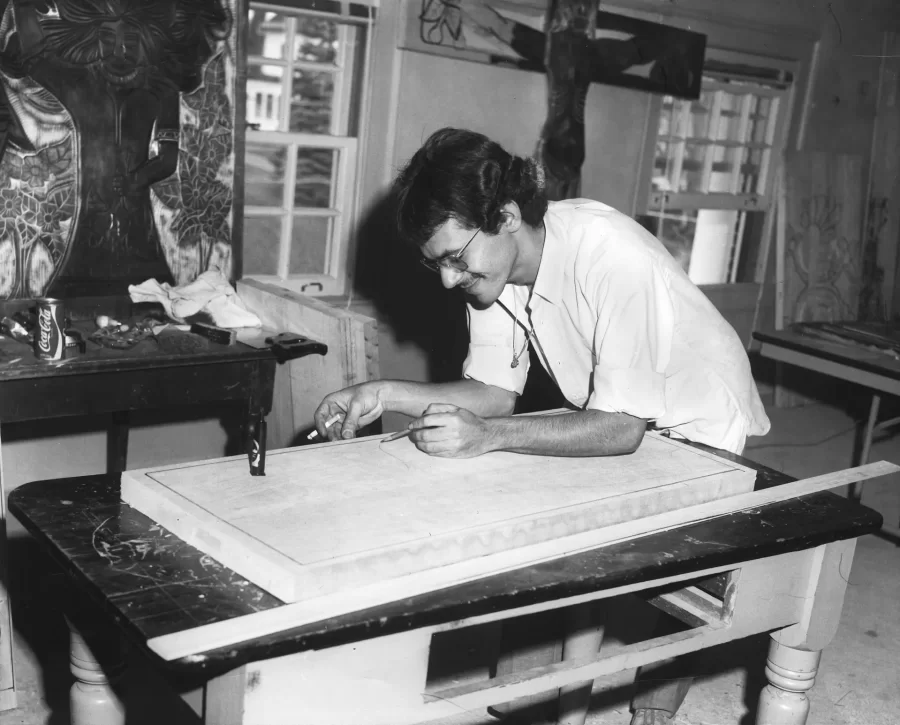

At a height of 7 feet and a width of 5 feet, 8 inches, the sculpture, which is safely stored at Bates, was carved from pine boards by Ziltamir Sebastião Soares de Maria, aka “Manxa,” a nickname he got from a white shock of hair he had a young age, a stain or manchinha.

Manxa was one of several visiting Brazilian artists who came to Bates starting in 1968 into the early 1970s under Partners of the Alliance, a federal cultural exchange program between Maine and its Brazilian sister state, Rio Grande do Norte. During Manxa’s time at Bates he created a number of works, leaving them as gifts to the college.

Manxa’s dramatically-scaled sculpture of Christ on the cross hews closely to traditional depictions of the crucifix, says Longsdorf, who teaches the First-Year Seminar “Arts and Spirituality” and whose doctoral dissertation looks at how U.S. college chaplains can embrace the arts to meet the needs of students of diverse religions as well as nonreligious students.

The sculpture depicts the Five Holy Wounds, Christ’s crown of thorns, and the initialism INRI, which stands for the Latin phrase “Iesus Nazarenus, Rex Iudaeorum,” or “Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews,” the sign that Pontious Pilate had affixed to the cross of Jesus.

What’s worth noting, Longsdorf says, is that Christ’s eyes are wide open, rather than closed and downcast, as in some depictions. “There’s pain and suffering, yet Christ’s eyes are open. It’s like we are awake to it.”

Another departure from tradition is that Christ is holding fruit and leaves in his hands. This might suggest that “his suffering is really about resilience and growth, which is different from most crucifix pieces.” Manxa left some open space around the arms of the sculpture, which “emphasizes the body over the cross,” Longsdorf says. “It draws your attention to the body and the wounds, both the pain and awakeness.”

This depiction refrains from implying the Resurrection, Longsdorf says. “This is still the Good Friday scene, the crucifixion, and Christian traditions try to let there be grief and sadness and loss between Friday and when Easter brings joy. You need that liminal space of mystery and grief, so that when the stone is rolled away, there’s surprise and joy together.”

Humberto Torres ’73 and his cousin Luiz Torres ’74, who both came to Bates from Sao Paulo, were at that April 1971 luncheon. Humberto now lives in the city of Natal in Rio Grande do Norte, in Brazil’s Northeast Region.

“I recall Manxa describing the fruit [that Christ is holding in his hands] as cashew, though the fruit is not exactly as he carved it. The leaves are from the cashew tree too.”

The cashew is a major cash crop in Brazil’s Northeast Region and Rio Grande do Norte. “Some families cultivate cashew as their main income. The nut grows outside the fruit; you need to roast them and crack them out of the shell.”

Manxa wrote the work’s title on the back in Portuguese: Auto Retrato Do Meu Povo, or “Self Portrait of My People.” To appreciate its meaning beyond religion, one must know about Manxa’s homeland in Brazil’s Northeast Region, says Torres. “It’s the poorest area of Brazil, and much worse in 1971 than today, plagued by long droughts and constant neglect by all levels of government, with poor health and poor education.”

With the phrase “my people,” Manxa might mean “the population of the interior of [Brazil’s] entire Northeast,” says Torres. “Some rhetoric compares the suffering of ‘my people’ to the suffering of Christ on the cross, and that faith in God — Jesus Christ — is their only hope of survival.”

Says Longsdorf, “It’s a really beautiful way to name the way, probably the religious practices of his culture, and also art in his culture, that are both so deeply a part of the shared lived experiences.”

At the bottom of the sculpture, Manxa added a personal detail, carving his name, the date of the Bates events, and a symbol of a circle and cross radiating light next to his name. “I interpret it as a carved globe, with the cross above and the rays, as representing Jesus in his glory,” Torres says. “It resembles the Catholic icon that depicts Jesus as a child with a globe in his hands.”

The circle has a diagonal line through it, which Torres thinks might suggest an armillary sphere, a navigation device associated with the Portuguese during the age of discoveries. “It made it possible for them to cross oceans and not be lost in the middle of nowhere. It has a line, the Milky Way, crossing the sphere. So the line carved crossing the globe could be taken from this instrument.”

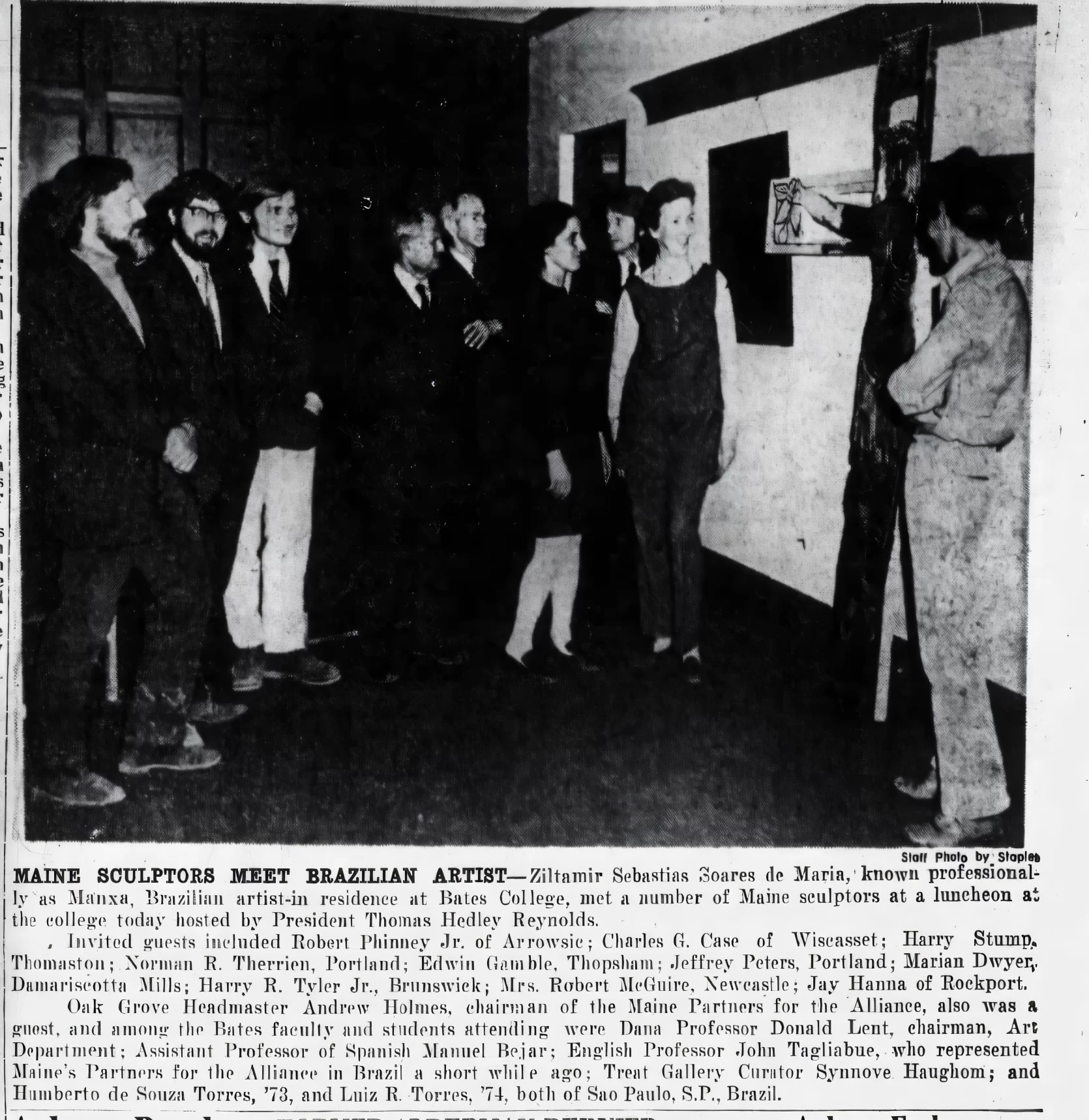

The guests who came to Bates to meet Manxa in 1971 were an eclectic group of both homegrown and from-away artistic talent reflecting the burgeoning and quirky arts community of early 1970s Maine.

There was Robert Phinney, a carpenter who hand-built a funky pine-board cabin on the Kennebec River that was the subject of Robert Petroski’s book The House with Sixteen Handmade Doors. And Dutch-born Harry Stump, known as “Maine psychic sculptor,” whose adventures in the Dutch Underground made him a hero. And sculptor Ronald Therrien, who cast the bronze statue The Lobsterman displayed on Canal Plaza in Portland. And sculptor and painter Nancy McGuire, identified in a newspaper article as “Mrs. Robert McGuire.”

The Bates faculty on hand that day reflected the college’s strengthening arts pulse, aided by arts champion President Hedley Reynolds, who hosted the lunchtime gathering in Chase and who would later secure major funding to build the Olin Arts Center.

Esteemed poet and Professor of English John Tagliabue was there. Three years earlier, he had traveled to Brazil with Partners of the Alliance. Also there was Don Lent, who had arrived a year earlier as Dana Professor of Art. Thanks to Lent’s work, Bates would add art as an academic major in 1972.

Torres recalls that Reynolds and others visited Brazil in fall 1967. “I was the interpreter for the group, with them full-time.”

Back home in Rio Grande do Norte, Manxa continued as a working artist, working in mediums that included steel, marble and concrete, as well as wood. “He left a lot of work all over the city, and some in other towns,” says Torres. He had a role in the creation of the huge Portico dos Reis Magos, or Statues of the Wise Men. “The administration building of the Federal State University has a huge work, and the chapel at the university has one of his works in concrete.”

Manxa died on March 19, 2013, in São Vicente, where he was born and lived for many years. An artists’ website has this personal statement, translated from the Portuguese:

“I am a plastic artist, sculptor in granite, marble, bronze and wood. I am also dedicated to agriculture and cattle and horse breeding. I love my children and nature with its ecosystem, thanking my beloved God every day for all this wonder of life that he has given us on earth.”