Herb Saucier was flabbergasted. Invited to attend a senior’s thesis-binding ceremony on the porch of Coram Library, he suddenly found himself at the center of attention.

“I was just standing there listening, and then she called me over. And oh my God! I had no idea.”

The senior was Martha Coleman ’23, a major in French and francophone studies from Seattle, whose thesis explores the evolving significance of French in Maine. A key part of the thesis-binding ritual is having a Bates friend help out, and in this case, the friend was a very surprised Saucier.

And as Saucier and Coleman maneuvered the 142 printed thesis pages into the traditional black binder, cheers went up from friends, faculty and staff gathered around.

Most times, the cheers are solely for the senior. This time, the cheers were both for Coleman and for Saucier, a well-known driver of the Bobcat Express, a small fleet of vehicles that shuttle Bates students to their community activities in Lewiston.

Coleman chose Saucier for the special occasion to show appreciation for his friendship and support during her senior year.

Over the past year, several times each week, at 7:15 in the morning, Coleman hopped into one of the shuttle vehicles, usually a Nissan Leaf, with Saucier at the wheel, for the 10-minute drive to Lewiston High School, where she taught French as part of her Bates education minor.

Maybe they only chatted for 10 minutes a day, about this or that, but the goodwill and friendship quickly added up. “Little interactions like that mean so much,” says Coleman.

Saucier is a 73-year-old retired Lewiston policeman whose father spoke only French, so he grew up learning and speaking French at home. During the commute to the high school, three days a week, “we would talk French,” says Saucier. ““She told me that she was doing her thesis on the French down here in Lewiston and what have you. She would ask me questions on my upbringing. That was really neat.”

Maybe they only chatted for 10 minutes a day, about this or that, but the goodwill and friendship quickly added up. “Little interactions like that mean so much,” says Coleman.

When it comes to the college’s shuttle, Bates students often talk about the lifts they get from the shuttle drivers, not just the transportation kind but the emotional kind, too, through caring words and support. “I just love any chance I can get to talk about how awesome the shuttle drivers are,” says Coleman, speaking for many students.

Growing up in Seattle, Coleman remembers photos of her father’s bike trip through France when he was a high school senior, and hearing him talk about exploring the country thanks to French skills he learned in school.

“I came to see studying French as a way of exploring the world,” says Coleman. But between COVID and other interruptions, Coleman decided to stay on campus for her junior year rather than travel abroad. “I could not fathom uprooting myself one more time.” In the end, she did explore the world, in a sense, without ever leaving Lewiston.

Coleman’s year-long honors thesis was advised by Professor of French and Francophone Studies Mary Rice-DeFosse, whose own scholarly publications include The Franco-Americans of Lewiston-Auburn, co-authored with James Myall.

The thesis has a section written in French that traces the history of French in Maine, and an English section focusing on community perceptions of the role and importance of French in Maine, drawn from recent reports on Maine’s Franco American communities, her own survey results, and interviews with several community members.

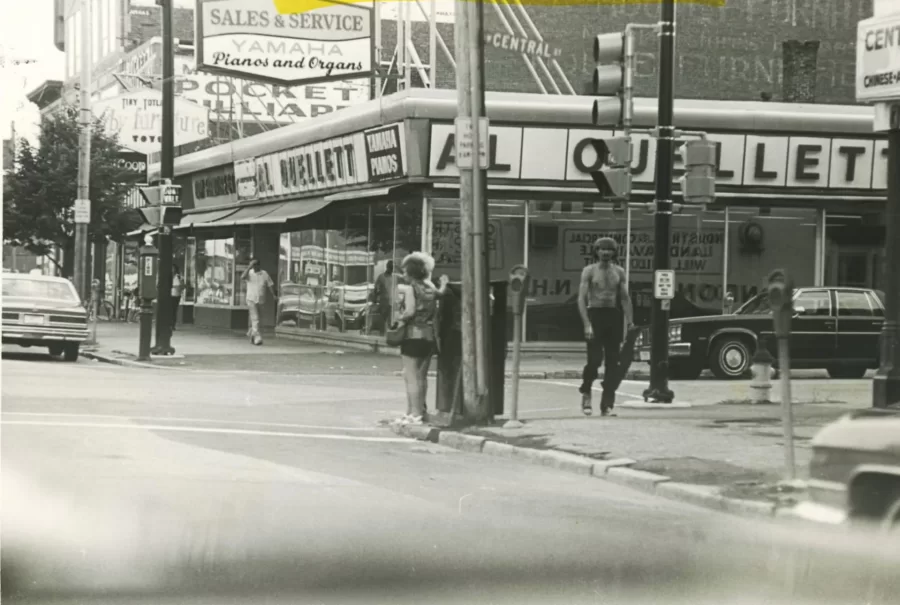

Maine’s Franco American communities, which thrived into the mid-1900s, were created through years of cultural exchange with the Canadian maritime provinces and with Quebec. And during Coleman’s morning commutes to the high school, she sat beside a man who personifies part of the history of French in Maine, where a quarter of residents self-identify as Franco American or French Canadian. In Lewiston, the percentage is near 60 percent.

Herb Saucier’s French-speaking father grew up during the Depression in the far northern Maine town of Madawaska, located on the St. John River, which is the U.S.–Canada border.

“When my father was born, there was no hospital in Madawaska,” Saucier explains. “Women would cross the bridge into Edmundton, New Brunswick, and have their babies there, and then they’d come back to the U.S. So my father was born in Canada, but raised in northern Maine.”

In his early teens, Herb’s father worked in the woods as a lumberjack, later moving to Lewiston and starting a family. His father worked as a truck driver for one of the mills. “I was born just down the street from Bates, at St. Mary’s,” he says. Growing up, “pretty much all we spoke at home was French. Even up till the time my father passed away in 2009, if I would go to his house or something to visit or whatever, help him with something, we always spoke French.”

While there are exceptions, Saucier’s generation of Franco Americans in Maine is considered the last to have learned French from their parents but not have been able to pass down the language to their children. “And I feel bad about that,” Saucier says. “I do wish my kids would’ve learned French. It’s something that has gotten lost. When there’s a break in the chain it’s kind of hard to keep it going.”

But the chain was, in many ways, forcibly broken by society’s bolt cutters. Through most of the 1900s, speaking French was not supported in local public schools. A 1919 state law, not repealed until 1969, banned the use of French in schools in all but foreign language classes. Even at Bates into the early 1990s, a rule prohibited Bates staff from speaking their native French in the presence of non-French speakers.

“Herb’s generation was doing the best they could to give their kids the tools they needed to survive a school system that, at the time, was really trying to discourage French,” Coleman says. “Or they’d been through that system themselves and seen how hard it was to go into a high school environment where speaking French wasn’t encouraged.”

Saucier and Coleman sometimes talked about his regret. “Herb was one of the first people to say to me, so candidly, that as much as he would love to see Lewiston go back to the way it was, in terms of its relationship with French, he didn’t see that ever coming to pass.”

Saucier put a face to a feeling that Coleman saw echoed as she got deeper into her thesis research, including surveys and interviews with elderly Franco Americans in Lewiston.

It was eye-opening. She’d been hearing various upbeat Maine voices, reading Maine texts, and taking in media that, quite appropriately, shared excitement about the future of French in Maine, especially with new French speakers immigrating to Maine over the last 25 years from African countries such as Togo, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Burundi, Djibouti, Rwanda, and Angola.

Yet, she says, the feeling of loss tinged with acceptance that Saucier and others voiced is real. The feeling needs to be heard as a reminder that “grief and guilt can be hard to see,” she says. “Grief still needs to be a part of the conversation about French in Maine, and we have to have realistic hopes. How do we hope for something new instead of hoping for a return to something old?”

The answer might come from what Coleman saw and learned about French culture in Lewiston through her classroom teaching experience at Lewiston High School.

She met and worked with students “who have never heard the term ‘Franco American’ and know little to nothing about Maine’s French history” but still showed interest, she wrote in her thesis.

And she engaged with students with French last names “who can’t speak or read the language themselves but still call their grandparents mémère and pépère, Franco American terms of endearment; with students who attended French elementary schools in the DRC before coming to the U.S.; and with students who speak French fluently with their families but still take French courses to help improve their writing skills.”

Coleman doesn’t try to make a definitive statement about the direction of French in Maine in her thesis, but instead hopes to “open a conversation about how the role and importance of French in Maine is evolving as the range of French speakers in the state expands and diversifies.”

She ends her thesis with a conclusion written in both French and English that offers a series of future-focused questions about how French language and culture in Maine can be supported.

Both conclusions end with two French sentences: Je ne sais pas. Mais j’ai hâte de voir ce qui se passera.

Translated by Coleman, it means, “I don’t know. But I can’t wait to see what will happen.”