What if you had to give up a word you use every day? That’s what a group of Bates student tutors were asked to do this fall as a way to consider how words — and the loss of words — influence our cultural identities.

When Nancy Campbell came to Bates in October to give the 2023 Otis Lecture on endangered languages, the poet also conducted a workshop with the college’s peer writing tutors to help them think more deeply about word choice and language.

The workshop exercise, in which the tutors were asked to give up a word, resonated strongly for Caroline Cassell ’24 of Woodstock, Vt., whose senior thesis in gender and sexuality studies is about the impact of language in the classroom.

“It’s easy to not pay attention to the impact of small choices and the impact they have on other people. However, language really shapes how we interact with one another. I think Nancy Campbell really speaks to that,” said Cassell, who is also majoring in sociology and theater.

Campbell, a poet, has traveled in and written extensively about the Arctic, including how indigenous communities in Arctic regions face challenges in maintaining their languages and cultural traditions. “The writing tutors wanted to hear about that,” said Bridget Fullerton, the director of student writing and a lecturer in humanities.

Campbell’s concern for endangered languages came out of the artist residency she held at a museum in Greenland in 2010, where she studied Greenlandic, which had just been added to UNESCO’S list of endangered languages. Following that experience, Campbell wrote The Library of Ice, a non-fiction book about her travels around Greenland and other glacial regions. This was followed by a book on global terms for winter weather, Fifty Words for Snow, which has been translated into 10 languages.

“In the Arctic, Indigenous languages are rich in traditional knowledge about the environment that can help us understand climate change,” Campbell said. “I was devastated to realize that not only the Arctic landscape and the human lives dependent on it are threatened by catastrophic climate change, but also the language.”

In her workshop with the peer tutors in the Student Writing and Language Center, Campbell brought her participatory art project The Polar Tombola, named after an Italian Christmas raffle.

After she developed the artistic exercise, in the mid-2010s Campbell took it on the road to events around the United Kingdom. During the tour, she gathered not just English words but Danish, Dutch, Farsi, Icelandic, Korean, and Spanish words, too. In 2017, Campbell published a selection of abandoned words in The Polar Tombola: A Book of Banished Words, an anthology featuring images of the hand-written words and poems on language loss.

As she has done elsewhere, Campbell gave each Bates student a Greenlandic word for them to try to use in their everyday lives — such as “akunagaa,” which means it is too late to begin, or unnuarpoq, which means there is no night any longer.

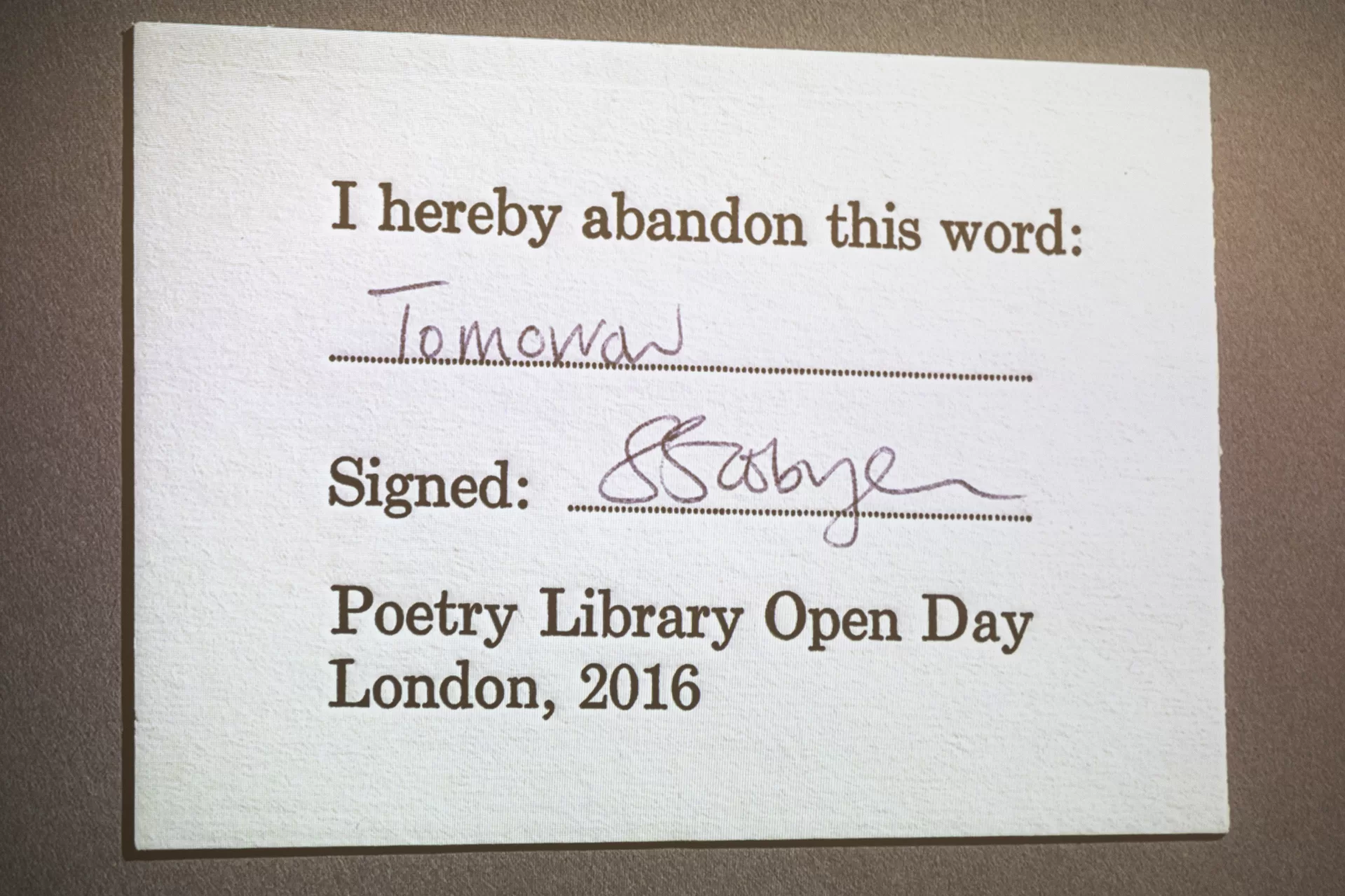

In exchange, she asked them to give up a word they felt was worth abandoning, a word they promised to never use again. Campbell hoped the exercise would generate a deep commitment, as well as an appreciation of the power of language.

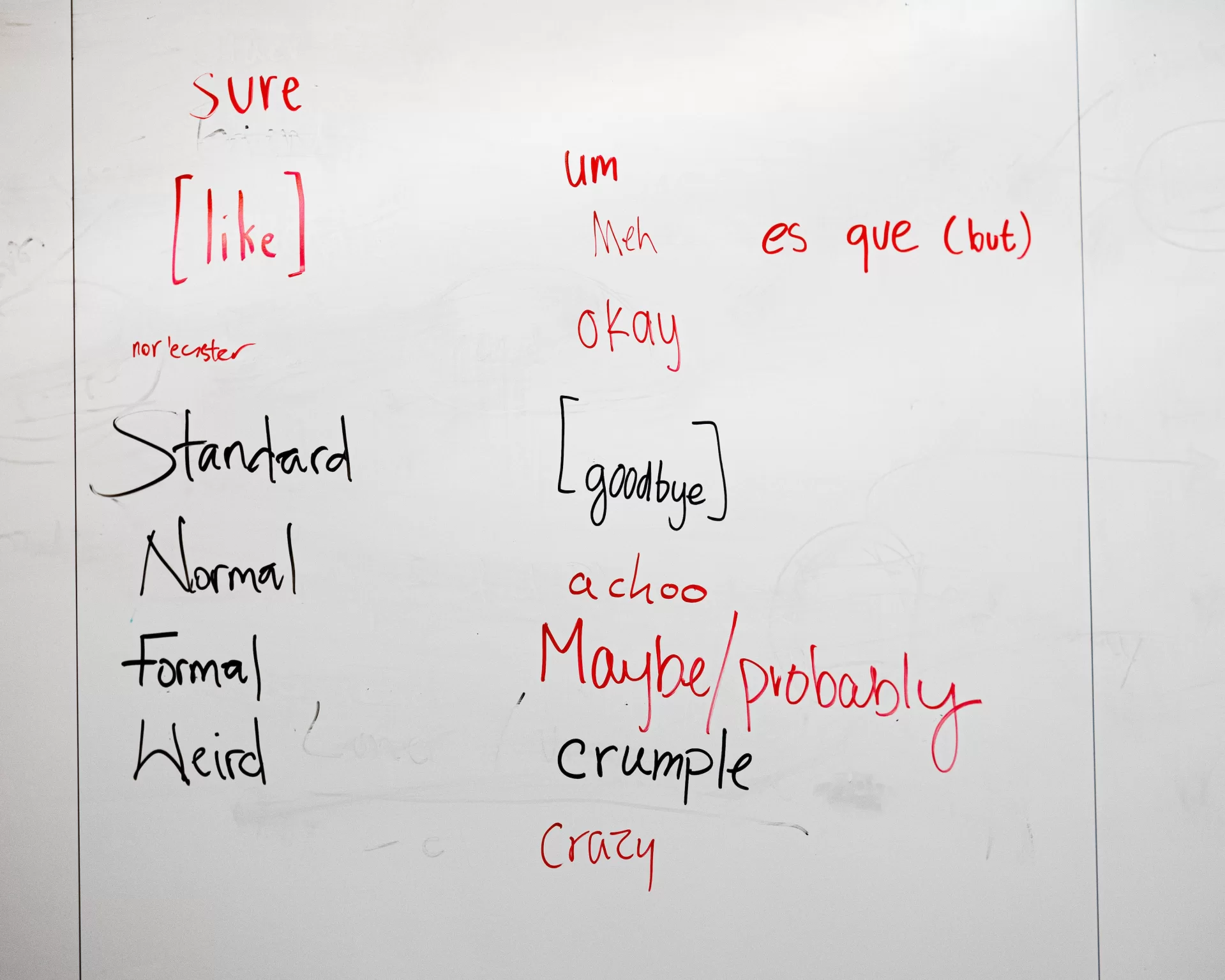

The students’ words were written on a white board, words such as “stupid,” “nevermind,” “sure,” “like,” “weird,” “normal,” and “crazy.” Campbell approached the workshop like a ritual, noting that the Bates words will be included in the second volume of the Banished Words anthology. “When people donate words to me, I take my duties as custodian very seriously,” Campbell said.

The Bates peer tutors also took the participatory art project quite seriously, especially since it coincides perfectly with one of the goals of the tutor’s umbrella program, the center: the imperative to embrace language diversity, recognizing that honoring the variety of language and dialects used within the Bates community is part of social justice work.

Aleisha Martinez Sandoval ’26 of Edinburg, Texas, appreciated the message inherent in The Polar Tombola: Be more mindful of the words, to be more concise, and to consider the effect they can have on people. She added that the center has been a good place to explore such ideas because it’s a supportive community, one that’s helped her become a better communicator.

Sandoval grew up in a bilingual household speaking both English and Spanish, and intends to give up the Spanish word “es que,” which translates to “but” when it precedes “excuses for one’s own actions,” she said. “As I move on in my professional career, I want to be known as someone who is not afraid of making mistakes, learns from them, and uses those findings to better themselves.”

Taking part in The Polar Tombola art project wasn’t Cassell’s first time trying to drop certain words from their everyday language. Upon arriving at Bates two years ago, Cassell decided to ditch the phrase “you guys” in an effort to use more gender-neutral language. The term, Cassell said, made a friend feel “really unseen, unheard, and uncomfortable.”

During The Polar Tombola participatory project, Cassell decided also to stop using the word “sure” because the word lacks enthusiasm and suggests hesitancy. “It was really great to have someone here who could speak to the power of the very small choices we make with words, something that might seem insignificant.”

After the Lewiston shootings on Oct. 25, Cassell decided to give up a third word: “Productive.” In the days after the tragedy, students were being asked when they’d dive back into their school work — when would they be “productive”? Living through that strange, horrible time made Cassell reflect on what it meant to be productive.

“Productive in our culture means go, go, go and work, work, work,” they said. “I wanted to reflect on how grief and rest and space also is producing something in ourselves.”

Of the center’s nearly 70 tutors, more than a third attended Campbell’s workshop. Campbell said she enjoyed the students’ robust debate that came out of the group exercise, such as questioning whether giving up the use of a word dulled its effect on you.

“Can you remove hate, for example, by eradicating the word?” Campbell posed. “If only!” The idea of giving up difficult and charged words prompted “very sophisticated questions from the students about censorship,” she said. “I felt we were coming to a group understanding of the frustrations encountered by those navigating language loss, whether through cultural change, or on an individual level in conditions such as aphasia.”

The question of using — or not using — explosive words is part of the work of Bates student tutors as they help their fellow students learn how to use inclusive and respectful language in their writing. “Words matter deeply,” Fullerton said. “Bad things make us want to give up horrible words like violence and hate, but when we give them up, how do we talk about them and cope with the problem?”

In the peer-tutor model in place at Bates and elsewhere, tutors are called upon to “carefully consider the words used in their peers’ writing,” said Fullerton, “even if those words are painful or unknown to the tutor — and must confront words that hurt or be curious about words that they don’t understand.”

Bates tutors, Fullerton said, “hold their peers accountable, asking questions and being curious: Why this word? Why here? What do you mean? We would all do well to ask ourselves such questions on a regular basis.”