When Anelise Hanson Shrout was in graduate school at New York University, she read an account about how the Choctaw Nation donated to Ireland during the Great Famine, not long after the U.S. federal government expelled Choctaws from their ancestral homelands in the American Southeast and forced them to resettle west of the Mississippi, the migration known as the “Trail of Tears.”

Reading that historical account of philanthropy in the 1800s led Shrout on a quest that spanned 15 years as she researched the international aid that came to the Irish people during the Great Famine, when thousands of people sent millions of dollars to suffering strangers in Ireland.

“The Irish famine went viral in ways that other crises had not. I thought at some point it might be more of an international relations story, but, ultimately, I kept coming back to the fact that this is really an Irish story, and I wanted to tell it as an Irish story,” said Shrout, an assistant professor of digital and computational studies and history.

In her newly published book, Aiding Ireland: The Great Famine and the Rise of Transnational Philanthropy (New York University Press, 2024), Shrout looks at how eight different groups in Europe and America supported Irish famine relief in the 1840s, often as an expression of solidarity and empathy, but also as a way to advance their own political agendas.

Shrout argues that in many ways these examples of famine relief launched the modern era of international humanitarian aid, examples of which are familiar to us now, whether 1971’s Concert for Bangladesh or Hope for Haiti Now in 2010.

In her book, Shrout looks at Quaker abolitionists in Pennsylvania, tenant farmers in rural New York, the Black congregants of a Baptist church in Virginia, the Cherokee and Choctaw nations, poor laborers in England, and more. But, oddly, in the examples of humanitarian aid Shrout researched, she found no previous connection between Ireland and the groups that donated to famine relief.

“This was one of the first times that so many people from so many different places sent money to people with whom they had no connection. And I think it changed people’s imagination of what international philanthropy can look like,” Shrout said.

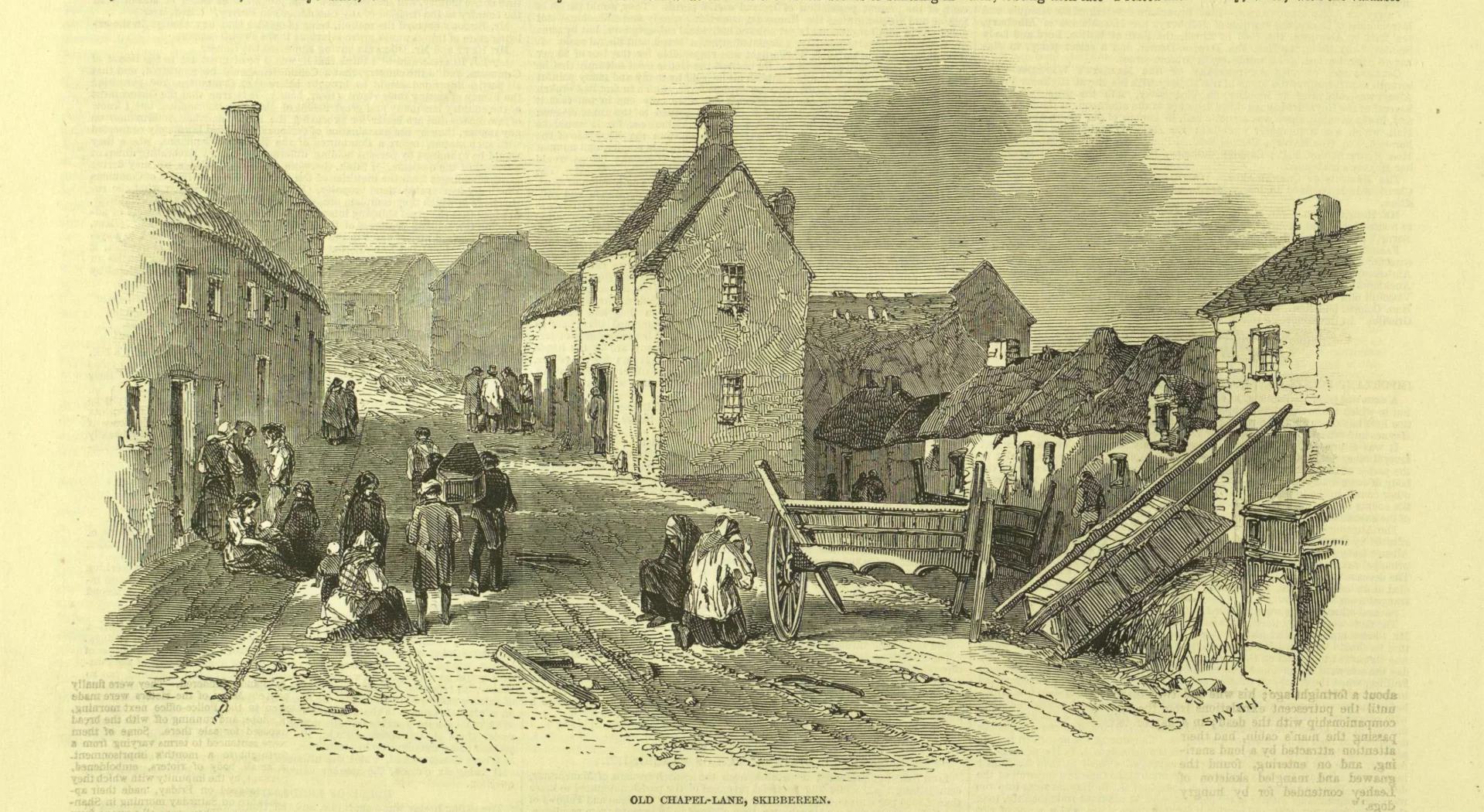

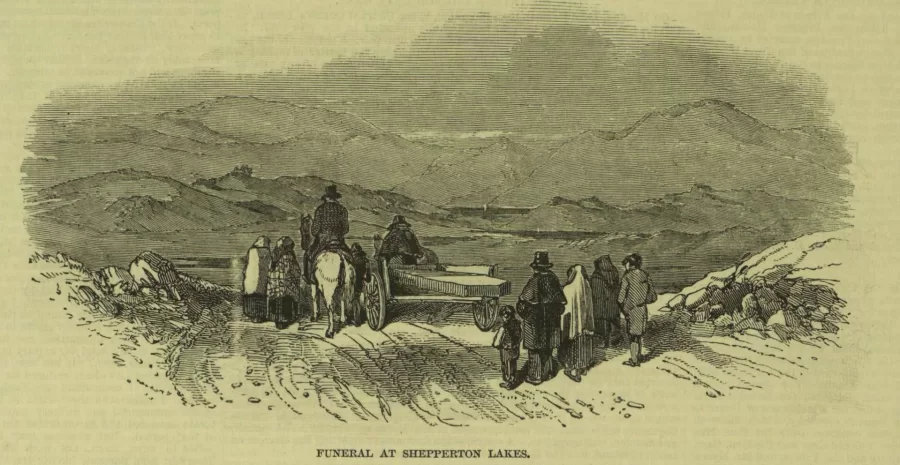

In the 1840s, when the entire island of Ireland suffered from a blight on the potato crop, which was a chief food source for the working class and poor, an estimated one million people died and another two million emigrated, reducing the Irish population on the island by nearly a fourth.

But the famine and disease that resulted happened at a time when people traveled the world by schooners, news spread slowly, largely via newspapers, and cultures around the world were not as interconnected as they are today. There was no precedent for large-scale international philanthropy, making the relief efforts Shrout documented odd for the time — and the first notable instances of global relief.

The flow of funds to the island wasn’t by chance or random. Instead, it seems, individuals and groups “picked Ireland because Ireland helped them to make some political points that were really useful to them,” Shrout said.

“I think we need to say out loud that these were people who were interested in helping distant suffering strangers, but at a time when they could have picked from a number of potential causes, some more local,” Shrout said. “You didn’t need to send money all the way to Ireland to help people.

“I understand why Irish people in the diaspora sent money back home. To be hundreds of miles away from your home and know that you might not ever see it again is traumatic. So I understand that. But when I got into this, I just kept finding these examples of people where I thought: ‘I don’t understand why you would’ve picked Ireland in this period?’”

As the great-great-great granddaughter of famine immigrants, Shrout had a personal interest in digging into the untold story of those who helped the Irish during the Great Famine. And her history acumen was matched in her research by her digital acumen. While writing the book, Shrout created a massive database listing thousands of donors, where they were from, and how much they gave — an extensive trove of information she hopes to use for a future project.

“I want to do something with that in a digital and computational studies mode, trying to think of them as a community using data visualization,” Shrout said.

As she researched Aiding Ireland, Shrout began to see how the flow of funds to the island wasn’t by chance or random. Instead, it seems, individuals and groups “picked Ireland because Ireland helped them to make some political points that were really useful to them.”

One unexpected philanthropist she researched was a slave owner in Alabama. Shrout makes the case that his intentions were politically motivated. She said that by donating funds he was suggesting that the people of Ireland were worse off than the enslaved people on southern plantations. As it turns out, a lot of famine relief came from landowners in South Carolina, North Carolina, and Virginia. Shrout said those donations supported enslavers’ claims that they were treating Black slaves better than the English landowners treated the Irish tenant farmers in Ireland.

“So they felt the fact that they sent money there proves that the slavocracy is a really benevolent system and the Irish are worse off, which is a wild idea,” Shrout said. “And then even more wild, they said, ‘Actually we are more like the Irish in this system because we are also oppressed by a centralized government that doesn’t have our best interest at heart.’ So the enslavers are saying the United States government is to enslavers as the British government is to the Irish.”

Another example of those giving for political reasons were tenant farmers in rural New York who wanted to build solidarity against a landlord class.

Other groups that sent aid donated funds as a show of true solidarity, although these also may have been politically motivated, Shout said.

“I think for the Cherokees and the Choctaws, there are these resonances about being subjects of colonialism and wanting to find ways to create a bridge between people who had experienced really similar things at the hands of the government. Certainly, that feels like a more reasonable claim,” than those made by enslavers, Shrout said.

Another example of those giving for political reasons were tenant farmers in rural New York who worked on small parcels of land on large estates around Albany. These poor farmers wanted to build solidarity against a landlord class.

“They talk about their donation to the Irish as being about building this transnational workers movement against landlords,” Shrout said.

As with the tenant farmers in rural New York, the names of donors in many of the groups Shrout researched were listed in newspapers at the time — but not always.

Congregants of the First African Baptist Church in Richmond, Va., which included both enslaved and free Black people, gave to famine relief in Ireland, yet newspapers didn’t list the names of the Black donors or the reasons for their donations, since most newspapers at the time were owned and run by white people. Shrout provides a compelling argument in her book that the donations from the Black congregants allowed them to make a public statement about their humanity, to juxtapose the barbaric, inhumane treatment of Black people in the South at that time.

“From the church’s founding around 1830 up until the (Great Famine), the congregants would occasionally raise funds for other church members. At no other point did they raise money for any group outside of the church — let alone a group outside of the church in another country,” Shrout said.

One of the more surprising acts of famine relief Shrout uncovered came from poor laborers in urban centers in England and Scotland, such as Manchester and Liverpool, where there was widespread anti-immigrant bias against Irish laborers who fled the famine in their homeland.

Shrout said the famine relief in this case was an effort to protest the so-called “corn laws’ at the time, which enhanced the profits of landowners and unfairly inflated food prices on the poor.

“Irish people were flooding into the cities,” Shrout said. “But then there’s also this political campaign to say, ‘We need to aid Ireland because the reason Ireland is starving is because of these laws called the corn laws.’ So there’s this moment of solidarity.”

Shrout launched Aiding Ireland at New York University’s Glucksman Ireland House last month. She also spoke about her book recently in an interview on The Irish History podcast. Among other places, she will present her research this June at the American Conference for Irish Studies in Limerick, Ireland.