Homing in on Green Design

In an age when volatile fuel markets and fears of environmental Armageddon generate big headlines, it’s astonishing to hear John Rossi ’88 talk about what wasn’t being talked about in architecture school in the early 1990s. Green technology? Efficient homebuilding? “That stuff wasn’t even on the map,” he says.

Then again, Rossi wasn’t necessarily looking for it. “I was very typical of a lot of people who recognized that while the environment is important and it’s worth keeping, it also feels way too big to know what to do about it,” says Rossi, who finished Bates with a degree in psychology.

Which is to say, a lot has changed in the last 15 years — both for Rossi and the building industry. Solar seems to be back from its near-death experience of the 1970s, wind has made a believer out of Texas oilman T. Boone Pickens, and geothermal heating systems are starting to find their way into American homes. And though not quite as sexy, there’s more-efficient drywall and cement, while a whole new generation of insulations and weatherstripping materials has hit the market.

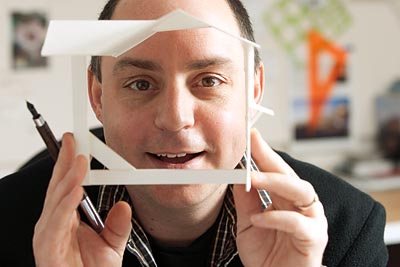

These are developments Rossi follows closely as principal of the Barendsen Rossi Collaborative, named for Rossi and his wife, writer and editor Lynn Dolberg Barendsen ’88. From the firm’s cozy third-floor office in downtown Newburyport, Mass., shared with a fellow architect, a landscape designer, and a Web designer, Rossi generates work that attempts to blow apart the notion that high efficiency and attractive design are somehow mutually exclusive.

“A lot of green architecture looks like a science project,” says Rossi, who exudes an infectious energy whenever the discussion turns to architecture and art. “It looks like an engineering experiment — a bunch of tubes and pipes. Who wants it? You don’t want it to look like a freak show. The aesthetics have to work.”

So do the economics. That’s why Rossi cringes at the argument that “green” architecture is a feel-good euphemism for “it’s gonna cost more.” The way he sees it, mainstream construction methods and the bigger-is-better mentality that has infiltrated the homeownership dream are plagued with inefficiencies and rife with hidden costs. Consider: Nearly 90 percent of all U.S. homes draw their energy from fossil fuels, and since 1950 the average size of a home has more than doubled. Add the fact that the U.S. building industry generates 40 percent of all landfill waste, and, well, you get the picture.

For Rossi, that picture came into focus first-hand. A Connecticut native who come from a long line of stonemasons, he studied in Rome during his Bates years and once worked in a sculptor’s studio. He recalls watching his dad carve out a living as a residential developer. Right after Bates, he embarked on a homebuilding business himself.

He watched as usable “waste” material was thrown out, inexpensive but inefficient appliances were installed, and the idea that a house should harmonize with its environment was stripped out of the building equation.

However inefficient, home construction, measured by square foot or by unit, “has never been less expensive than right now,” says Rossi, as anyone who’s seen a row of McMansions lining a golf course can attest. “It’s cheaper because it’s more generic. In many ways we’ve worked hard to idiot-proof the building process. Buy one of those, add two of that, and you’ve got a building.”

Point being, it is more expensive to hire an architect like Rossi and actually make decisions. “But I’ve found that when a homeowner discovers that they do have choices, the doors start to open for them.”

Rossi’s former company, PowerHouse, was started in 2003 as a reaction to this inefficient, one-size-fits-all process. The idea was to harness the model of the modular home construction business to create smartly designed “green” houses. “[Modular factories] already offer a more eco-friendly process,” says Rossi. “The site impact is less. The waste is less. And they come to your property in a few trucks, as opposed to making 55 trips a week to the lumberyard.”

In total, PowerHouse constructed four houses and eight small buildings called “PowerPods” whose green features include:

- proprietary thermal break system (to prevent heat loss) in the wall construction;

- Forest Stewardship Council-certified woods;

- innovative solar technology;

- and a special remote home-monitoring system that allows owners to check the home’s temperature and humidity levels from any computer with an Internet connection.

The press and the industry raved about the PowerHouse approach to style and efficiency, but a rush of venture capital or a big deal with a developer never materialized. Coupled with what Rossi describes as the company’s own lack of a strong business foundation, the venture seemed destined to fail.

In early 2008, Rossi walked away from it. “We kept being told that what we were doing made a lot of sense and that we clearly knew what we were doing,” says Rossi. “But nobody wants to be the guinea pig. It’s a building, not a little widget, and when you’re having a half-million dollar home built, you don’t really want to experiment.”

As he tries to carry forward concepts from PowerHouse, including modular construction, Rossi compares the current entrepreneurial landscape for green builders to “the Wild West, or like the Internet in its infancy. There are many startups out there, some like mine with cool ideas, proven success, and even lots of free media attention. Most are not making much headway yet — especially with this economy — but some are going to be moneymakers.”

The economy’s impact on the sustainability movement is something David Braslau ’84 faces each day as a vice president of the Projects and Services Group at Constellation Energy, a Fortune 500 company that specializes in energy exploration and delivery as well as infrastructure improvements. Based in Boston, Braslau oversees the design and execution of large-scale energy-related renovation projects for clients like hospitals, universities, and the federal government.

When he completed his master’s in environmental planning in the mid-1980s, Braslau — a veteran of Bates’ first efforts around energy awareness — figured he was at the dawn of an era when energy efficiency would be all the rage. “But then I started knocking on doors and found that people weren’t all that interested in energy conservation,” he says. “It was all about the bottom line — nobody wanted to add new features to a project if that meant raising the cost. And that’s really the same today.”

As recently as mid-2008, Braslau saw a resurgence of interest in sustainability among institutional clients. But with the souring economy and a major drop in energy prices, some Constellation clients who had expressed interest in progressive long-term energy solutions — solar photovoltaic rooftop systems, solar-electric hybrid lighting, or vegetated roofs that help reduce heat loss, for example — are now dialing back their green plans.

“It all drops back to the economic equation,” says Braslau. “We can show them the environmental impact if they don’t do something, or what their carbon footprint is, but if you’re a hospital or university CFO, how do you justify doing something if you can’t show it’s cost-effective?”

At the consumer level, Halsey Platt ’88, a high-end remodeler and cabinetmaker based in Groton, Mass., argues that the greenest way to meet the human need for shelter is through home renovation rather than building new. “It’s the ultimate recycling. You don’t use up undeveloped land for a new home.

Platt has been in the building business almost as long as he’s been away from Bates, but it wasn’t until 2000 that clients even started asking about environmentally friendly and energy-efficient construction. Nearly nine years later, with more than half of his customers demanding “greener” building in the form of better windows, sustainable products, native woods, or higher-end heating systems, Platt still sees an alarming lack of proven green options for the regular consumer.

Take the electrical box. A typical home has about 300 of them, says Platt. And yet, pay a visit to your regular big-box hardware store and what you’re shown is a unit made out of polyvinyl chloride (PVC), a controversial plastic that can’t be recycled. Want one made out of steel? Sorry. Your electrician will tell you he only installs those on commercial jobs — though he could get them at extra material and labor cost. “Your clients have to be able to spend more, plan further ahead, and look harder,” says Platt.

But what constitutes “green” and what doesn’t isn’t always so clear. “You have to be careful because there is a lot of greenwashing out there,” he says. In one recent renovation of a space for an organic food company in Arlington, Mass., Platt explored the use of a newer insulation material made from recycled denim. “Part of my concern about this product was whether or not we could stand behind it,” he says. “We have to guarantee to our client that this insulation isn’t a perfect home for mice or mold.”

And if it fails, it’s Platt Builders that takes the hit. “Having to come back three or five years down the road and rip it out is certainly antithetical to the entire green movement,” says Platt.

John Rossi is convinced that green building has moved beyond amateur hour. “The more [people] see that it really works and it isn’t funky or hard to live with, and the more we are able to deliver and deliver well, the easier this will all become,” he says.

Rossi compares green building to the personal computer. “Who had one of those 25 years ago? Now we can’t think of living without them — they do more, they’re cooler, more fun, and cheaper. Same deal.”

By Ian Aldrich

Ian Aldrich, a freelancer living in Boston, wrote about energy trader Dan Rice ’73 in the Fall issue.