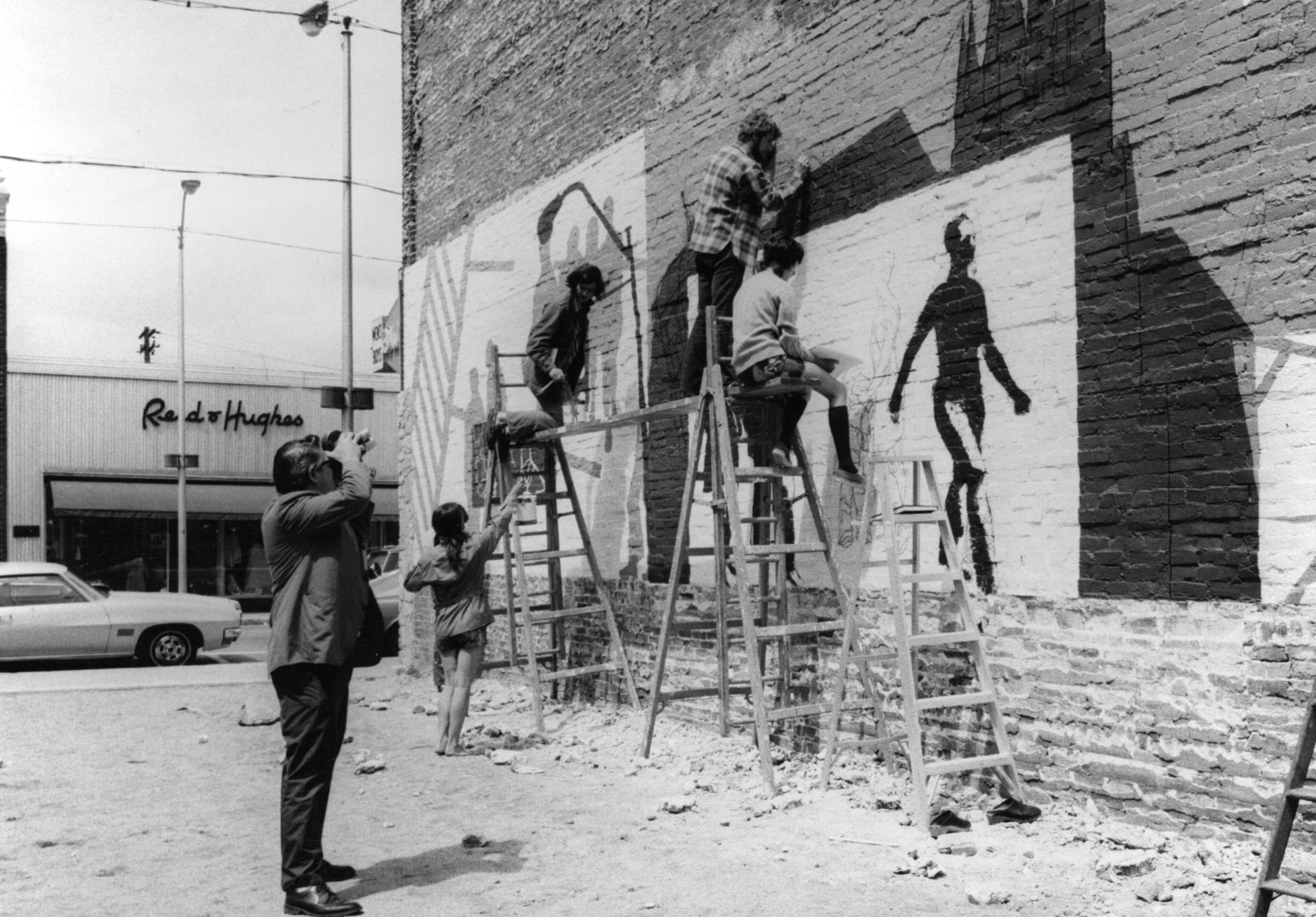

A 1971 project to paint a colorful mural on a Lisbon Street brick wall was a sign of the times.

Donald Lent, Bates’ new Dana Professor of Art, was looking for a Short Term project that would connect students to his civic efforts around urban renewal in Lewiston.

The city, wanting to open a new pedestrian walkway linking upper Lisbon Street and Park Street’s retail and parking areas, had demolished a wood-frame building next to Edward’s Clothing Store, at 114 Lisbon St.

The store’s newly exposed brick wall caught Lent’s eye. Encouraged by the city’s Urban Renewal Authority, Lent got permission from the building’s owner to paint a mural on the wall, then selected 13 students from 30 who showed interest.

Lent had a knack for putting students on the right tasks. Norton Virgien ’74 was interested in filmmaking, so Lent charged him with producing a documentary about the project with his 8mm camera. Now an animated-film director in Los Angeles, Virgien told Bates Magazine in 2004 that the “thought processes that went into telling that story are still the ones I use today.”

Guided by Lent, the students developed sketches on butcher paper and painted the mural in white, blue, red, and a particularly tenacious traffic yellow. The mural’s narrative was straightforward: pedestrians moving through familiar Lewiston places. “I wanted the mural to connect to people in town,” Lent says. Silhouettes of downtown features included the onion domes of the Kora temple and the spires of the Basilica of St. Peter and St. Paul.

Bates had just approved an art major, and Lent was no fool: He stocked the project mostly with freshmen eager to prove their artistic zeal. Those were heady times, says Jonathan Lowenberg ’74, who came to Bates to major in chemistry but switched to art partly because of the mural project.

“It was a great dynamic,” he recalls. “We were enthusiastic about the major, and the project was something completely new for all of us.”

In ’71, urban renewal still seemed like a good thing. Lent recalls the project “feeling so integrated with what was going on in the town.” Lowenberg, whose Mirror portrait shows him painting the mural, remembers everyone thinking that the “mural was going to be there a long time.”

But one day a decade later, Lent saw workers sandblasting the mural. “That felt awful,” he says. Lisbon Street was losing its retail businesses, and the clothing store had closed, to be replaced by an Asian restaurant.

“Maybe,” Lent says, “the mural was more like an installation, designed for a specific place and time. After a while, it just didn’t fit into the plan.”

Today, the wall belongs to an Indian restaurant. Tiny white and yellow paint chips from the mural still cling to the bricks. And if you stand back, you can still see the outline of one of the mural’s pedestrians, walking through the scene.