Benjamin Mays’ living legacy

The great civil rights leader never forgot Bates. And it works both ways.

By Doug Hubley

In 1986, about a dozen Bates people found themselves deep in rural South Carolina looking at a shack.

They were looking at a shack, but seeing the starting point of a journey whose consequences were nothing short of transformational for a man and for a nation.

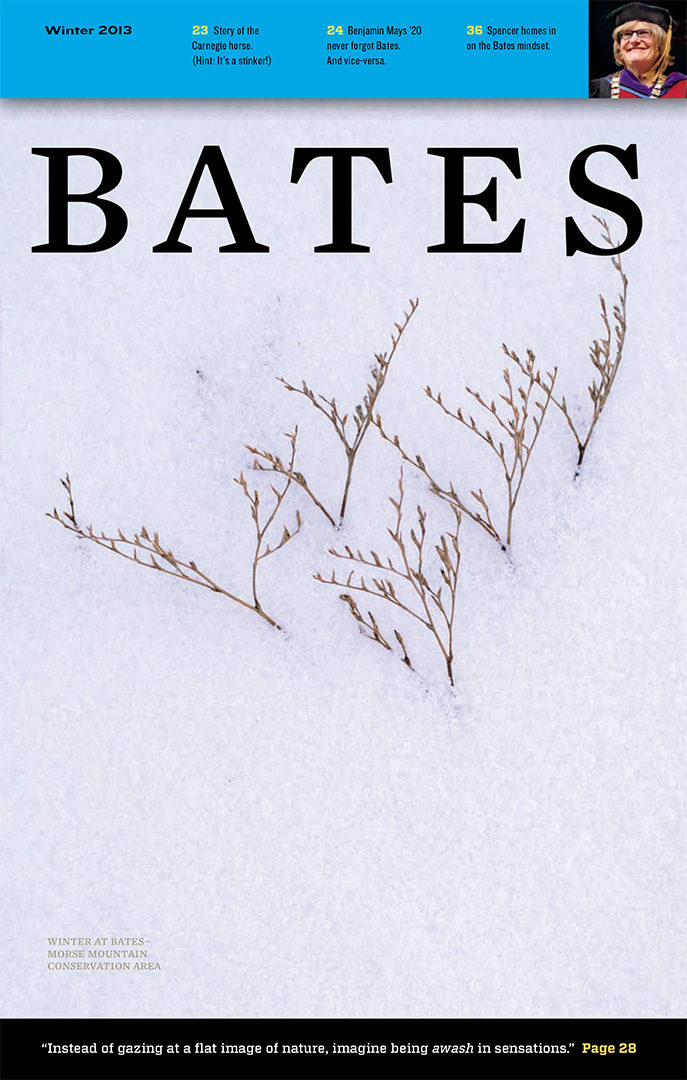

Benjamin Mays ’20, photographed in 1980 when he returned to Bates for his 60th Reunion. Photograph by Jim Daniels.

The shack was the Greenwood County birthplace of Benjamin E. Mays ’20, the civil rights theorist, educator, preacher, Morehouse College president and mentor to the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. — in short, schoolmaster to the civil rights movement, to paraphrase recent Mays biographer Randal M. Jelks.

The Bates group comprised students in a Short Term religion course investigating the black church in America. For them, the shack near Epworth, S.C., was one seminal stop in a Southern itinerary that resembled a kind of “Benjamin Mays Tour” because Mays was linked to so many of its destinations.

There in the countryside, the visitors from Bates were closing a circle. They were learning about a man who might have had a much different life, perhaps a less consequential life, without Bates. Bates had shaped Mays, and now his legacy was shaping these students, and back through them, the college itself.

Even 29 years after Mays passed away, that circle remains intact. Many people know of Bates because of the college’s influence on his life. And Mays’ influence is more present than ever on campus, whether expressed in the college mission statement, or in the recollections of Bates people who knew him, or in campus speeches, notably the Oct. 26 inaugural address by Clayton Spencer (see page 38).

Former slaves, Mays’ parents were sharecroppers. Their dwelling has since been moved to the Dr. Benjamin E. Mays Historic Preservation Site, in Greenwood, S.C., but when the Bates group visited, it was “out in the middle of a field,” recalls Associate Dean of Students James Reese, who was part of the group led by an acting college chaplain, Rob Stuart.

“Personal and political freedom and formal education were inextricably bound together for Mays.”

The group talked about starting life in that field in the Jim Crow era — Mays’ earliest memory was of a white mob threatening his father — and ultimately heading off to Maine for a college that promised something better. In 1986, the distance from Greenwood to Lewiston “was palpable,” Reese says.

“But in 1917, it was like going across the universe. That really resonated with us.”

In that year, Mays entered Bates as a 23-year-old sophomore after a year at Virginia Union University, where two Bates alumni on the faculty encouraged him to try their alma mater. Starting with a friendly encounter with a Bates student on the train coming north, Mays was pleasantly surprised to discover that racism in Lewiston was more the exception than the rule.

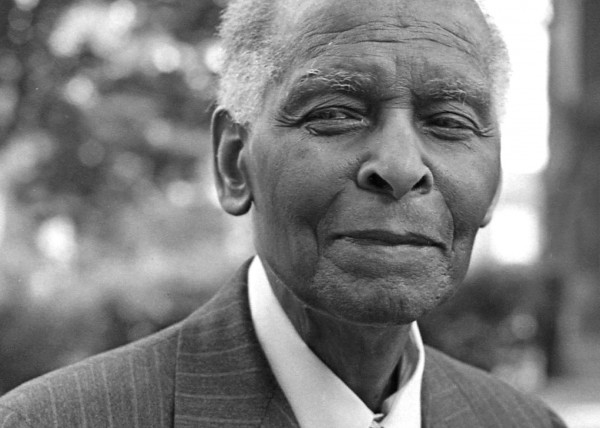

Mays poses with his 1919 debate teammates. Mays’ drive to succeed academically came from wanting to prove “that superiority or inferiority in academic achievement had nothing to do with color of skin,” he wrote in Born to Rebel. Front row, from left, Arthur F. Lucas ’20, Robert B. Watts ’22, Edward H. Brewster ’19; back row, Charles M. Starbird ’21, Benjamin E. Mays ’20, Charles P. Mayoh ’19. Photograph courtesy of Muskie Archives and Special Collections Library.

Mays came here not only for a better education than a person of color could reasonably expect down South, but to prove his intellectual equality to whites. “How could I know I was not inferior to the white man, having never had a chance to compete with him?” Mays recalled in Born to Rebel, his 1971 autobiography.

Proof soon abounded. He won a speaking award in his first year at Bates, finished his senior year as captain of a triumphant debate team and was one of 15 in his class to graduate with honors, among other achievements.

“I concede academic superiority to not more than four in my class,” he wrote in Born to Rebel. “I displayed more initiative as a student leader than the majority of my classmates. Bates College made these things possible.”

At Bates, Mays “found a way to chart a course in which he could find the intellectual resources he needed, gain confidence in his ability and then to leave to do extraordinary things,” says Marcus Bruce ’77, who is the inaugural Benjamin E. Mays Distinguished Professor of Religious Studies at Bates.

Or as Mays himself famously summed up his experience in Born to Rebel: “Bates College did not ‘emancipate’ me: it did the far greater service of making it possible for me to emancipate myself, to accept with dignity my own worth as a free man.”

He later earned advanced degrees at the University of Chicago, but it was at Bates that he laid the groundwork for “a new biblical interpretation that could mobilize black communities to take action against Jim Crow’s enforced apathy,” Jelks writes in the 2012 Mays biography Schoolmaster of the Movement. Mays’ studies in religion steered him toward an intellectual structure for both his profound Baptist faith and his personal mission “to uplift his people,” as Jelks puts it.

In the writings of theologian Walter Rauschenbusch and others, Mays learned about the Social Gospel, a Protestant movement that advocated for a church that would actively address societal ills — of which there was none more exigent to Mays than American racism.

Mays later came to understand the Church as central to both the persistence of racism and its amelioration. Racist whites cited Scripture to defend their prejudice, and blacks used the Church to defend their sanity and solidarity. And in that unity also lay the foundation for a civil rights movement.

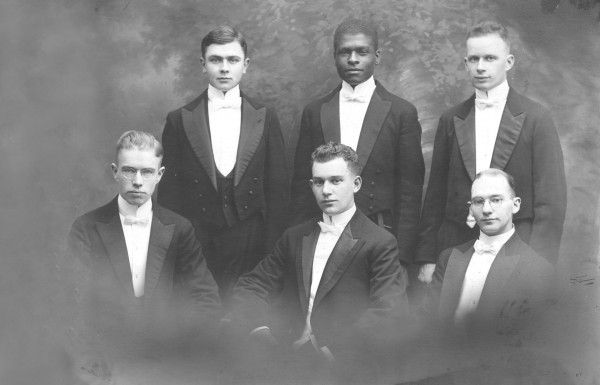

Mays delivers the final eulogy for the slain Martin Luther King Jr. on April 9, 1968, at Morehouse College. Photograph courtesy of Howard University.

Mays saw in certain Baptist tenets — “freedom of conscience, the dignity and worth of every man, each man’s individual right of direct access to God,” in his words — a moral basis for the powerful rebuttal to racism that he would promulgate to generations of students. Especially during his tenure as Morehouse president, from 1940 to 1967, he “laid the intellectual groundwork for social change throughout the South among black churchgoing college students,” Jelks writes.

Both resounding and intellectually sound, Mays’ rhetoric was the ammunition that these students needed to overturn the racist discourse of the Jim Crow South. Mays, says Bruce, “employed and deployed religious rhetoric to address urgent issues of religious, political and social importance. This is certainly one of the lessons that he passed along to his student, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.,” as well as to such political and civil rights leaders as Julian Bond and Andrew Young.

People who know about Benjamin Mays tend to know about Bates.

James Reese, who was a child when he first encountered Mays, at a college football game in Knoxville, Tenn., has stayed close to Mays’ legacy. Reese accompanied former Bates President Elaine Tuttle Hansen to Greenwood in 2011 when she spoke at the dedication of the Mays Historic Preservation Site.

Hansen explained to an attentive audience that Bates, in rewriting its mission statement in 2010, had tipped its mortarboard to Mays by declaring itself “dedicated to the emancipating potential of the liberal arts.”

“That really resonated with the audience,” Reese recalls. “They leaned back, confident that Bates understood what Dr. Mays was about. I was so glad to be there for that moment.” In fact, Reese points out, people who know about Mays tend to know about Bates. The warm relationship between Morehouse and Bates has roots in his story; and Reese even has an anecdote about bringing his parents to visit a friend whose hospitality suddenly blossomed when she learned he worked at Bates.

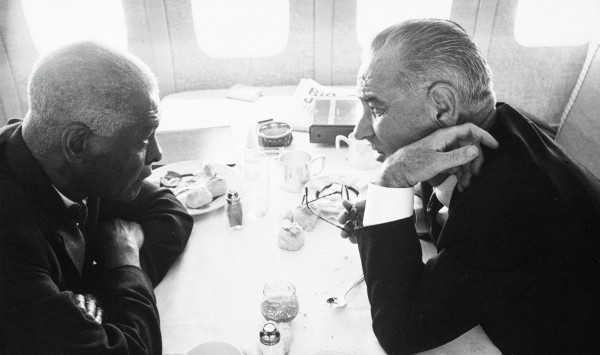

In June 1963, Mays and then-Vice President Lyndon Johnson confer while en route to the state funeral of Pope John XIII. Yoichi Okamoto/LBJ Presidential Library

If Bates is known elsewhere because of its role in Mays’ achievements, those achievements keep Mays alive in the campus consciousness. He is much in evidence when Bates observes Martin Luther King Jr. Day, which always includes a debate with Morehouse. Bates named its Residential Village campus center for Mays, adding to a list of monuments around the nation that includes an elaborate memorial, incorporating a statue and Mays’ tomb, at Morehouse.

Most important, Mays lived and taught values that Bates calls its own. Other Northern institutions refused Mays admission due to race, but Bates has always been open to all races.

“Personal and political freedom and formal education were inextricably bound together” for Mays, Jelks writes; so they are here.

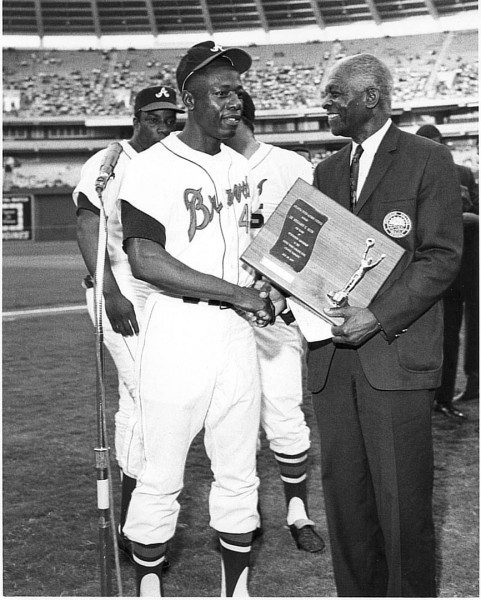

In this undated photo, Mays talks with baseball great Hank Aaron of the Atlanta Braves. Photograph courtesy of Howard University.

Mays’ passion was social engagement; his scope was global — Gandhi, whom he met, was influential in his thinking. And his style was audacious. These are all Bates hallmarks.

“Exploring the legacy of Mays is a way to discover something about Bates as well,” says Bruce. “He continues to help us understand who we are as an institution, and the kind of education we provided in the past, and can provide in the future.”

The revised mission statement, Bruce says, presents the liberal arts education “as being about emancipation, freeing yourself from certain kinds of fears, or conventions, or ideas that are limiting. It enables you to see, and think, and live in new ways.” And if most of today’s students will likely never face the difficulties experienced by minorities back in the bad old days, the determination that Mays forged in the struggle remains inspirational.

“He’s an extraordinary example of faith, of fortitude, of persistence and clarity of vision,” Bruce says. “Bates provided an opportunity for him, but at the same time he continues to provide us with a great deal. It’s just a matter of exploring his legacy.”