For MLK Day 2014, award-winning journalist offers ‘Dream’ analysis

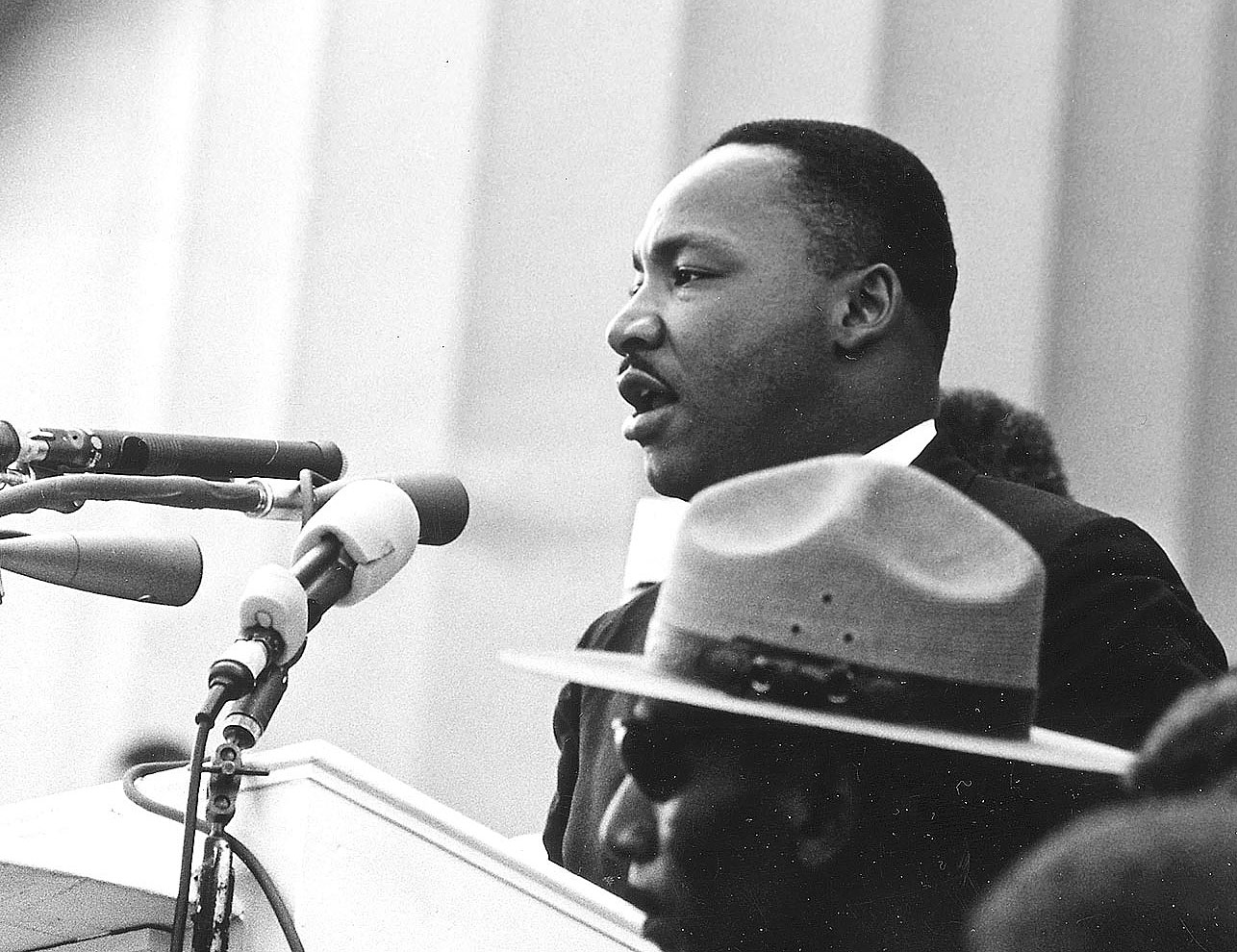

Journalist Gary Younge offers the Martin Luther King Jr. Day keynote address, an analysis of King’s “I Have a Dream” speech, in the Gomes Chapel at Bates on Jan. 20. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

More than 50 years later, the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom has become as much cultural touchstone as historical milestone.

Even as its context and complexities have faded from mass awareness, the March has evolved into a symbol of progress for civil rights. Epitomizing this perception is Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech, his best-known address.

Bates dedicated its 2014 Martin Luther King Jr. Day programming to the March, the Speech and their relevance today. And two speakers during the morning keynote session on Jan. 20 offered quite different perspectives on the events of Aug. 28, 1963.

As always, Martin Luther King Jr. Day 2014 at Bates encompassed a rich schedule of programming that included Sunday evening’s memorial service and on Monday, a debate with Morehouse College, numerous workshops and panels, and the sold-out evening performance by Sankofa. Learn more:

- A slideshow of MLK Day 2014 events at Bates.

- Video of the keynote session and the Bates-Morehouse debate.

- The full schedule of activities.

- More about the day’s participants.

- Members of Sankofa preview their performance.

- A report from the debate.

An inspired and inspirational view came from someone else named King who happened to be on the scene in D.C. that day — U.S. Sen. Angus King.

Bates President Clayton Spencer chats with U.S. Sen. Angus King (I-Maine) during the college’s 2014 Martin Luther King Jr. Day keynote session on Jan. 20 in the Gomes Chapel. King offered reminiscences of the 1963 March on Washington. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

In remarks to about 400 people in Gomes Chapel, King said that hundreds of thousands of people came together in the nation’s capital that hot August day in the service of an “idea that’s important and still radical today: All men and women are created equal.”

A more granular view came from the keynote speaker, English journalist Gary Younge, author of a 2013 book that examines both the history of the March and the Speech, and their place in today’s context.

It’s true that the “Dream” speech marks a transition after which “the question of American apartheid is no longer alive,” said Younge. Yet, if legal segregation is dead, racism is alive and well, and the kind of profound systemic change that King dreamed of still eludes us.

The keynote session began with jazz by the Three Point Trio and a welcome by keynote host and Associate Dean of Students James Reese. Next, the college’s new dean of the faculty reminded his listeners that Bates explicitly links education and service, privilege and obligation.

“Hand in hand with study and contemplation is informed and ethical action,” said Matthew Auer, who came on board as dean and vice president for academic affairs in July 2013.

With a rhetorical tip of the hat to the Bates mission statement and Martin Luther King mentor Benjamin Mays ’20, Auer said, “the emancipating potential of the liberal arts is not a spectator sport.” That theme became a motif of the morning.

President Clayton Spencer introduced Angus King, former Maine governor elected Independent senator in 2012. King, who as a 19-year-old watched the March on Washington program from his perch in a tree on the National Mall, reprised his remarks from last August’s national 50th-anniversary celebration, at which he represented the Senate.

“As it was once said of Churchill, Martin Luther King on that day mobilized the English language and marched it into war,” King said, “and in the process caught the conscience of a nation.”

Midway through the program, Acting Multifaith Chaplain Emily Wright-Magoon echoed Auer’s theme as she read pledges for action gathered from the audience at Sunday night’s MLK worship service.

Accompanying Wright-Magoon were Gospelaires Brittney Davis ’14, Megan Guynes ’11 and Courtney Parsons ’15, who sang a luminous “This Little Light of Mine” in three-part harmony. This welcome addition recognized the role of women in the civil rights movement generally, and specifically honored three singers present at the March: Mahalia Jackson, Camilla Williams and Marian Anderson.

Members of the Gospelaires perform during Bates’ 2014 Martin Luther King Jr. Day keynote session. From left, Brittney Davis ’14, Megan Guynes ’11 and Courtney Parsons ’15. (Sarah Crosby/Bates College)

Charles Nero, head of the MLK Day planning committee at Bates and professor of rhetoric and American cultural studies, let on that keynote speaker Younge had originally planned to speak at Bates during last year’s MLK events. But Younge, who writes for the British newspaper The Guardian, instead covered President Obama’s inauguration.

The timing was advantageous, though, because in the meantime Younge got a book published: The Speech: The Story Behind Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s Dream.

At Bates, Younge painted a picture of events behind the March that, paradoxically, made it seem both inevitable and fortuitous.

For instance, local civil rights protests in the months before the March were cresting, all but necessitating some kind of grand national gesture. Quoting author Ryszard Kapuscinski, Younge cited the psychological tipping point where “a harassed, terrified man suddenly breaks his terror, stops being afraid . . . Man gets rid of fear and feels free. Without that there would be no revolution.”

“People don’t know when there’s history in the making. They just know they have to do something,” Younge added, referring to Sen. King’s earlier exhortation to seize opportunities for action when they appear.

Serendipity helped to define the March as well. King, for example, didn’t initially plan to use the “I Have a Dream” language, a staple of his repertoire, during the March. And yet, at the right moment, he set aside his notes and his lecturer persona, and preached those immortal words — perhaps persuaded by gospel singer Mahalia Jackson, who sat nearby urging him on.

Occurring during an event designed as King’s introduction to the nation, the Speech had something for everybody. For patriots, roots in foundational American values; for liberals, appeals to the labor and peace movements. And African Americans could be supremely proud of this demonstration of black will and intelligence.

Appreciating the presenters during the 2014 Martin Luther King Jr. Day keynote session at Bates College. (Sarah Crosby/Bates College)

But today’s exalted view of King and the Speech differs dramatically from its perception five decades ago, Younge pointed out. In the 1960s, King was unpopular among whites, a sentiment exacerbated by his growing opposition to the Vietnam War, which many Americans supported, and to the capitalist system.

Younge concluded that the nation has mistaken a victory in the battle against segregation for a victory in the war against racism. By many measures, African Americans have gained little in terms of prosperity and well-being since the March.

It’s true, Younge concluded, that “King’s speech was an appeal to hearts and minds, the vision of a society in which race was not the defining and crippling factor that it once was, and to some extent still remains.”

“But he did not dream of better people. He dreamt of a better system.”