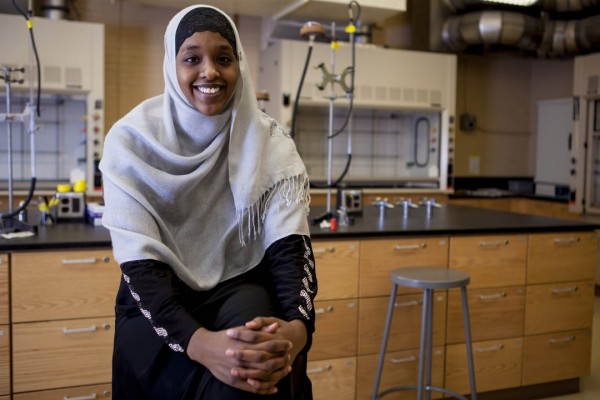

Intersections between health and culture draw Phillips Fellow Mohamud ’15 to Tanzania

In Tanzania during the summer of 2013, Asha Mohamud ’15 learned a valuable lesson about perspective.

Volunteering at an HIV and AIDS clinic in the southwestern town of Tukuyu, Mohamud met client after client whose HIV test came back negative. Despite what she knew about the high incidence of the disease in the region, she came to think of a negative diagnosis as the norm.

“The danger of falling into a routine is that you fail to realize what you . . . describe as ‘typical’ is life-changing to someone else,” Mohamud wrote in her journal. “Day after day, we’d inform people their test results were negative. They’d leave thanking us and repeating over and over, ‘Thank God, thank God, thank God.’

“I became immune after hearing this for the millionth time.”

Mohamud made that journal entry the day after she was jolted from this sense of complacency. A young man came into the clinic smelling of ginger, which he had likely eaten to sooth his cough, and describing symptoms of what he thought was malaria.

A nurse suspected AIDS and persuaded the man, a newlywed, to be tested for the virus. The tests work fast and a little indicator shows the diagnosis: one line if the test is negative, two lines if HIV is present. While they waited together for the result, Mohamud says, “you could see his hands trembling.” After a few minutes, two lines were showing.

Fortunately, AIDS is no longer a guaranteed death sentence. The clinic where Mohamud was volunteering, supported by a Phillips Fellowship from Bates, is run by a local NGO, KIHUMBE (an acronym for a Swahili phrase meaning “home-based service providers of Mbeya,” the major city in that part of Tanzania). The organization was founded in the early 1990s by a nurse-midwife who was among the first in the region trained to deal with the disease, and is still led by women.

For Mohamud, a biology major with a minor in religion, Tanzania was a step toward a life goal: returning to Africa to practice medicine in the service of public health. Daughter of a Somali refugee family, Mohamud spent the first eight years of her life in Nairobi, Kenya, and her family moved to Lewiston when she was 9.

Here at home, she volunteers at a free clinic at the Trinity Jubilee Center, translating for Somali clients, taking blood pressures and helping in other ways. She also has a job-shadowing arrangement at a local nephrology clinic, work that will inform a Bates research project.

Mohamud went to Tanzania, she says, because “I was interested in exploring both the medical and the cultural aspects that play into HIV and AIDS.”

In parts of Africa, “any kind of illness is hidden out of fear of being ostracized,” she says. KIHUMBE founder Florence Mwakanyamale understood that the disease couldn’t be prevented or treated if no one talked about it. It was typical for sick people to isolate themselves at home. Mwakanyamale found ways to overcome this isolation and keep patients active in the community.

“It’s an interesting dynamic, because even here in Lewiston, in the Somali community, we’re adamant about hiding our illnesses,” Mohamud says. “Even though there’s a lot of education about various illnesses, it’s still something that’s not talked about. I was always fascinated as to why that was a factor in our community.”

KIHUMBE provides HIV education and other preventative measures in addition to treatment. During her two months in country, Mohamud took part in all of these activities.

But the counseling work in the clinic made the deepest impression on her. She learned to steel herself to give bad news about an AIDS diagnosis. The worst day involved four HIV-positive clients: a mother and son, and a woman and her orphaned grandchild.

“Working with KIHUMBE and seeing how HIV and AIDs impacts someone’s life brought the human element in medicine to life for me,” she says.

Mohamud also witnessed first-hand the economic gulf between the developed and developing worlds. “I was encouraging our AIDS patients to eat three square meals a day,” she says, since some of their medications should be taken with food. “And I’d have the patients quickly rebutting, saying, ‘Listen, I can barely afford one meal.'”

“I was forced to recognize and to essentially check my privilege,” she says. “I’m still processing it.”

Nevertheless, she adds, “the patients’ outlook kept my spirits high. After her diagnosis, one mother looked at the nurse and me and said, ‘I am grateful God brought me here. I found out early, so I can now take the medicine and watch my children grow up.'”