Neither naive nor cynical, Oscar winner Stacey Kabat ’85 reflects on her domestic-violence activism

Not long ago, Stacey Kabat ’85 was talking with a friend, a longtime reporter for The Boston Globe, about the infamous case of Jared Remy, the serial abuser in Massachusetts who ended up murdering his girlfriend in 2013.

Stacey Kabat ’85 talks to students in a film theory course taught by Jonathan Cavallero, assistant professor of rhetoric. She brought her Academy Award, saying, “It’s fun to hold it, so I always feel like sharing.” Students passed it around and, yes, it’s heavy. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

They talked about how everyone around Remy — the courts, police and social systems — had failed to protect the victim.

Kabat and the reporter agreed: “It felt like we were right back in the 1990s,” she said, a time when activists like Kabat were lighting a fire under the problem of domestic violence and reporters covering their work were helping to put it on the national agenda.

Kabat related the anecdote during her visit to campus earlier this week, including a public talk on Sunday and visits to two classes on Monday taught by Assistant Professor of Rhetoric Jonathan Cavallero.

In Cavallero’s class on film theory, Kabat talked about how the early 1990s were heady times on the domestic violence front.

In 1992, she won a Reebok Human Rights Award for her efforts with abused women, including work to found the nonprofit Peace At Home.

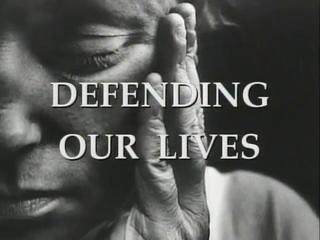

In 1994, she was part of the team that won an Academy Award for the documentary film Defending Our Lives that exposed the severity of domestic violence in the U.S.

A year later, Kabat presented at the NGO forum during the United Nations World Conference on Women, held in Beijing.

Kabat, who was just in her early 30s, was already dubbed a “veteran laborer in the vineyards of social justice,” wrote the Los Angeles Times.

“Things were snowballing, steamrolling. We were moving and changing,” Kabat said.

In Cavallero’s class, Kabat screened the 1998 documentary Strong at the Broken Places, for which she was a co-producer.

Listening to Stacey Kabat ’85 are Rosy DePaul ’17 of Los Angeles, Mark Charest ’15 of Westbrook, Maine, Nora Kenny ’17 of Brooklyn, N.Y., and Gerald Nelson ’17 of San Antonio, Texas. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

A follow-up to Defending Our Lives, the film tells the story of four people, Arn Chorn-Pond, Max Cleland, Marcia Gordon and Michael MacDonald. Each survived horrific violence in their lives and used their experiences to help other victims of violence and to create powerful new identities for themselves.

Cleland, who would become a U.S. senator from Georgia, lost two legs and an arm in Vietnam after a hand grenade exploded in his hand.

“I lay there shattered and dying,” he says in the film. Heroic efforts — a team of five physicians, hours in surgery and 43 pints of blood — saved his life. “That, it turned out, was the easy part,” he said. “You face a stark reality. You will never be the person you were, yet you don’t know who you will be. You don’t know you the hell you are.”

The film has a more hopeful story arc than Defending Our Lives. With terrifying personal testimonies and graphic photographs of domestic violence by photojournalist Donna Ferrato, the film was “like a grenade,” Kabat says, that blew open the topic of domestic violence.

“It was radical,” Kabat says, to show Ferrato’s images. “It was so different. No one had yet been able to expose visually this hidden family secret.”

So what happened to shift the national gaze from domestic violence?

“I’m not a cynical adult because I know that change can occur,” says Stacey Kabat ’85. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

Bill Clinton, who signed the Violence Against Women Act in 1994 and talked about growing up in a violent home, lost credibility after Monica Lewinsky. Then, 9/11 and resulting wars forced America’s attention away from the domestic agenda.

When she was 18 and heading to Bates, “domestic violence” wasn’t a word, Kabat has said. She had been raised in a violent home but there was no way to talk about that in college.

In the 30 years since then then, “I’ve gone from being ashamed and not be able to talk about it, to being able to talk about it and create programs of change and seeing people change and develop. It’s amazing.”

Today, as Kabat sees example after example of America’s violent streak (such as the NFL’s clueless initial reaction to Ray Rice beating his wife), she is “appalled. It’s frustrating. We should be done with this already.”

“But I thought [the Oscar] would help the violence to stop.”

She says that America, notwithstanding the current “It’s On Us” campaign and other efforts, has yet to “take hold of the issue and address it in a concrete, prioritized way.”

And that’s the bittersweet legacy of winning an Oscar.

“It did bring clout to the issue and put a stamp on it that said, ‘This is important,'” says Kabat, who soon after delivered the commencement address at Simmons College, won a number of awards and traveled the country speaking and showing Defending Our Lives for a couple years.

“But I thought [the Oscar] would help the violence to stop. That was the naive kid in me.”

Sarah Koe ’16 of Portland, Ore., listens as Kabat talks about her career trajectory as an activist. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

Today, Kabat is 51 and has two children, one in high school and the other 8 years old. And if she’s no longer laboring in the vineyard, she’s still in the field. Transitioning from running her nonprofit, Peace At Home, she is now a maternal/child health nurse and a lactation consultant at Mass General.

“After 9/11, it was so hard to receive aid for what we were doing,” Kabat says. “I couldn’t be fundraising, working, speaking, counseling. It was too much. You can only do 20 years of that. My husband said, “Stace, the Beatles only had 10 good years.’ So I feel OK!”

She’s no longer that naive kid but Kabat still has fire in her belly. “I’m not a cynical adult because I know change can occur,” she says.

It comes from “your actions with people you meet every day. How you interact with your peers, how you interact in your community, how you choose what you want to speak out on, how you vote and how you get involved.”

The best example is right in front of you, she said.

“Bates was founded by abolitionists. And there’s a reason for that. They wanted us to think about being part of social change.”