Slideshow: MLK Day at Bates, and a community’s embrace of a daunting and complex theme

In photographs by Phyllis Graber Jensen and words by student and staff writers in the Bates Communications Office, here’s a look at events and moments from the college’s 2015 MLK Day observance and how the Bates community took on a daunting and complex theme: “From Selma to Ferguson: 50 Years of Nonviolent Dissent.”

7:05 p.m., Jan. 18

Duncan Reehl ’17 (right) of Milford, N.J., and Divyamaa Sahoo ’17 of Kolkata, India, perform “Strange Fruit,” during the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Interfaith Service in the Gomes Chapel. Written in 1936, the famous song “paints a gruesome picture of a gruesome reality — the lynching of black people,” said Emily Wright-Magoon, acting multifaith chaplain.

“I was at first concerned, but then grateful when I heard that Sahoo and Duncan were going to play ‘Strange Fruit’ because it painfully reminds us, as we begin our service, just what is at stake: people’s lives. It reminds us of the violence that has torn those lives away. We are here tonight to ask — from the perspective of a variety of traditions — what are the spiritual, religious, and ethical roots of nonviolent dissent?… Even if you are not a religious person, where do you root your commitment to justice? How do you stay hopeful? If you’ve committed to nonviolence, why?” — Jay Burns

7:58 p.m., Sunday, Jan. 18, 2015

Najeeba Syeed-Miller delivers the address at the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Interfaith Service in the Gomes Chapel. Her theme, “Radicalizing Dr. King: A Transreligous, Transnational Vision of Beloved Community,” explored the spiritual, religious and ethical roots of nonviolent dissent.

9:06 a.m., Monday, Jan. 19, 2015

President Clayton Spencer talks with MLK Day keynote speaker Peniel Joseph. At left is Vice President for Academic Affairs and Dean of the Faculty Matt Auer. In her welcoming remarks, Spencer said:

“We take pride in our college’s founding principles that have helped to give events like today’s MLK Day observance very specific and recognizable Bates qualities. But we, too, need to challenge ourselves in the present to live up to the ideals marked out for us by those who have gone before.

“Like, for instance, Benjamin Mays, Bates Class of 1920, the great theorist of civil rights and mentor to Martin Luther King Jr., who delivered the final eulogy at King’s funeral, explaining the paradoxical link between the ideals of non-violent dissent and the violence it often begets. Mays said: ‘[King] gave people an ethical and moral way to engage in activities designed to perfect social change without bloodshed and violence; and when violence did erupt, it was that which is potential in any protest which aims to uproot deeply entrenched wrongs.'” — Jay Burns

10:01 a.m., Monday, Jan. 19, 2015

Marcus Bruce ’77 (left), the Benjamin E. Mays Distinguished Professor of Religious Studies, listen to Joseph’s talk with James Reece, associate dean of students, both of whom have contributed in big ways to the MLK Day tradition at Bates.

Bruce played a pivotal role in the tradition of suspending classes to engage in community discussion. The onset of the Gulf War on Jan. 16, 1991 — the U.S.’s first major armed conflict in a generation — rocked the Bates community. But by embracing its role as a teaching and learning community, and relying specifically on its own heritage, Bates re-established a degree of equilibrium: King’s birthday was coincident to the date of the war’s beginning, the Bates faculty moved quickly to make the connection relevant and compelling. In a special meeting on Jan. 18, the faculty voted to cancel classes on Monday, Jan. 20, “in honor of and to reflect upon Dr. King’s contributions to world peace, and to reflect upon the issues of peace and justice in the Middle East.” Those were the words of Marcus Bruce. — Jay Burns

10:09 a.m., Monday, Jan. 19, 2015

An author, professor of history at Tufts University and authority on Black Power studies, Peniel Joseph gives the King Day keynote address. Joseph described a divergence prevailing today:

“Even as we celebrate Martin Luther King Jr., we divorce King the icon from King the political activist who’s willing to speak truth to power and who said that ‘injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.’ … We celebrate the dreamer, but divorce the dreamer from the actual dream.” Yet the emergence of the Black Lives Matter movement holds out hope for real progress, Joseph said. “So many young people, like in the 1960s, are actually not just demonstrating and protesting — they are organizing,” he concluded. “They are organizing on behalf of social, political, economic and racial justice. And they are organizing to try to fill that gap between democracy as an ideal in America, and democracy as an actual living, breathing fact.” — Doug Hubley

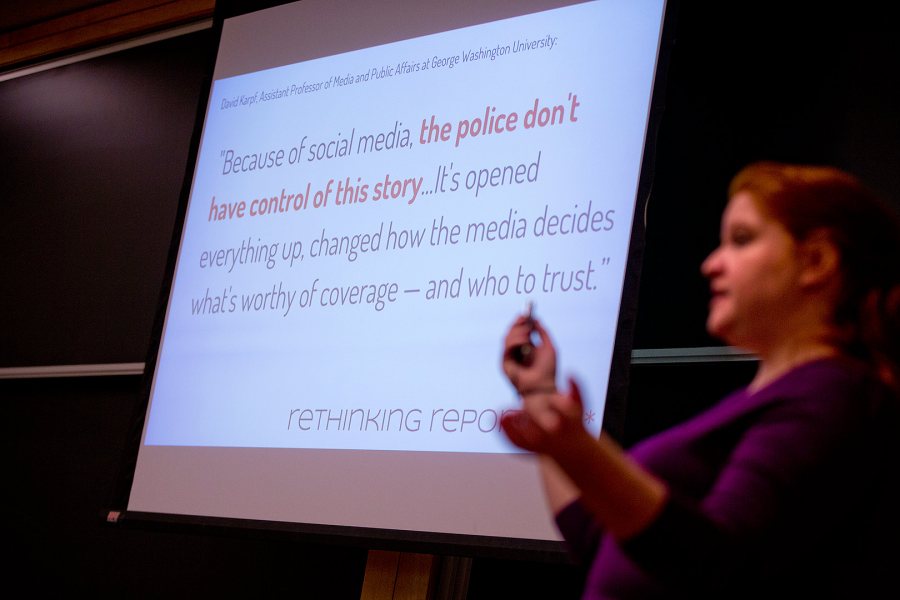

10:55 a.m., Monday, Jan. 19

During the panel discussion “Social Media and Political Change,” Megan Goodwin gestures at a quote about social media, the news media and Ferguson — how six million Tweets in the first 10 days after the Aug. 9 shooting “opened everything up, changed how the media decides what’s worthy of coverage — and who to trust.”

Goodwin, a Mellon postdoctoral fellow in the humanities at Bates who did her undergraduate work in journalism, said that “almost all public awareness [about Ferguson] came through social media.” She added that it’s not only that the police don’t have control of the story, as stated in the slide. “I would suggest that it’s bigger. Mainstream media outlets don’t have control of this story, either. And there’s not one story. We’re getting the complexity of this movement through a complexity of social media tools. And I think that’s exciting.”

Also participating were Margaret Imber, an associate professor of classical and medieval studies who leads the digital humanities efforts at Bates, and Vice President for Academic Affairs and Dean of Faculty Matthew Auer, whose scholarly work includes social media and public policy. — Jay Burns

11:28 a.m., Monday, Jan. 19

Students text answers to racial issues during the workshop “Text It,” which sought to teach students how to discuss uncomfortable topics, particularly race.

At first, participants texted anonymous ideas and perspectives that were displayed on a screen for the group to discuss. Questions began small, aimed at getting attendees comfortable. “Offer some suggestions to improve daily life at college or in school” was one. (Answers included a Starbucks on campus.) The next one was: “Do you feel comfortable talking about diversity with people you don’t know?” On the projection screen, attendees saw that responses were split evenly. Through these early discussions, audience members didn’t talk. The only sounds were fingers tapping on screens and that little “whoosh” of an iPhone sending a message. — Grace Kendall

11:32 a.m., Monday, Jan. 19

A few minutes later, the “Text It!” workshop moves from anonymous to in-person.

Facilitators posed the question “Do you have any prejudices?” and asked attendees to answer via text before breaking into groups to discuss. Common answers via text were prejudices against the wealthy; one texter admitted a perception of black people as less intelligent, knew it was wrong but could not shed that perception.

In group discussions, several participants said that being a member of a minority group sometimes meant being expected to speak for that group in academic settings.

One of the final questions was a yes/no poll that was answered in person, by a show of hands — no texting. It was, “Do you think race relations have improved since the election of Obama?” The vast majority said, “No.” — Grace Kendall

12:55 p.m. Monday, Jan. 19

Drawn by the prospect of a meaty discussion about the Michael Brown shooting and related events, an expectant crowd fills the Edmund S. Muskie Archives for the “Perspectives on Ferguson” event.

First, a panel comprising students and faculty from Bates and away answered questions submitted previously: What is the best way for the Black Lives Matter movement to advance without a clear and visible leader? Can violence ever be appropriate in a protest movement? How can white people help? (“Help in a way that doesn’t get in the way,” responded panelist Jamilia Davis ’15 of Oak Park, Ill.) And how can I, as a student, ensure that the movement gains traction?

“Every protest I’ve been to has been led by college students,” said moderator Alex Bolden ’15 of Cleveland. “Don’t relegate your power to simply here on campus…. You have more power than you think.” — Doug Hubley

1:26 p.m. Monday, Jan. 19

After the panel, groups of students, faculty and staff explore their responses.

Also in the discussions were Lewiston-Auburn residents, including Lewiston High School students involved last December in a poster action at LHS protesting the grand jury decisions in the deaths of Michael Brown and Eric Garner. The need for better communication came up repeatedly in the groups, often in conjunction with appreciation for Bates’ commitment to making MLK Day a time for discussion.

But in the end it all gets down to one-on-one, some students said. If the events in Ferguson and Staten Island have opened your eyes but not those of your friends, said Nicole Kanu ’15 of Little Rock, Ark., don’t change your social circle — change your friends’ minds instead. “Remember that you were one of them once.” — Doug Hubley

1:07 p.m. Monday, Jan. 19

In the Fireplace Lounge, members of the Bates community share short original writings addressing King’s legacy or texts that have inspired them.

Stacy Smith, lecturer in education, was one reader. Last fall, she and First-Year Seminar students read King’s “Letter from Birmingham Jail” in class. Smith read letter that she wrote to King. She wrote, in part:

“I too have a dream for America, my America, our America. This is a claim I feel slightly embarrassed to make — in the wake of your noble visions, as a white girl, as a product of the postmodern generation, and most particularly, as an academic. Dreams are not popular currency amongst my crowd; here, reason is king. Since you’ve been gone, even while you were still here and Malcolm cast off doe-eyed white girls as outsiders to your movement, it’s been awkward at best, presumptuous at worst, to claim anything as shared ground. As ours. To speak the unspeakable without social approbation for somehow getting it grievously wrong.

“But, you’ve taught me, through your words and by your example, and I’ve learned on my own journey through these years, that you can’t really get love wrong. You can’t get open-heartedness wrong. Or goodwill. Or forgiveness. These are practices. You live them. You embody them. You exude them. In communion with others.” — Jay Burns

2:49 p.m. Monday, Jan. 19

Artist Jonathan Frost discusses the paintings he created in response to a tour of historic civil rights sites in the South. His “Series on Claudette Colvin” depicts the 15-year-old girl who was arrested in March 1955 in Montgomery, Ala., for violating the law of segregated bus seating, several months before the famed Rosa Parks case.

This painting shows Colvin sprawled on the floor of her bus and being dragged by police. Colvin once retold the incident: “I started crying, but I felt even more defiant. I kept saying over and over, in my high-pitched voice, ‘It’s my constitutional right to sit here as much as that lady. I paid my fare, it’s my constitutional right!’ I knew I was talking back to a white policeman, but I had had enough.” — Jay Burns

3:56 p.m., Monday, Jan. 19

Zoë Seaman-Grant ’17 of Charleston, S.C., makes a point during the Benjamin E. Mays Memorial Debate in the Olin Concert Hall.

A packed audience was treated to the verbal and intellectual firepower of four of the nation’s — perhaps the globe’s — top college debaters, two from Morehouse College and two from Bates, who put on a rousing show as they argued the motion “This house believes that violent resistance to state oppression is justified.”

Refuting her opponent’s argument, Seaman-Grant all but levitated as she delivered, seemingly without taking a breath, an articulate and impassioned dissertation on the justifiable role of violent dissent. Joining her on the Government side was Morehouse’s Jonathan Carlisle ’17 of Marion, Ala. The Opposition team featured Bates’ Alex Daugherty ’15 of York, Pa., and Da’von Boyd ’17 of Chesapeake, Va., from Morehouse. — Meg Kimmel

4:09 p.m., Monday, Jan. 19

During a parliamentary-style debate, a debater can signal interest in offering a “point of information” during an opponent’s speaking time, exemplified below by Seaman-Grant (notice her hand) during the spirited rebuttal by Da’von Boyd ’17 of Chesapeake, Va.

When he rebuffed her repeatedly, which is acceptable and strategic, Seaman-Grant’s posture shifted from questioning to “what-EVER,” much to the audience’s delight. The Olin Concert Hall crowd, encouraged by Bates convener Chris Crum ’17 of Littleton, Colo., who explained the do’s and don’ts of parliamentary debate, including the important point that the debaters did not choose their sides, got into the act with enthusiastic applause, foot stomping, whistles and hoots. — Meg Kimmel

5:33 p.m. Monday, Jan. 19

John Collantes ’18 (front) of Park Ridge, Ill., takes part in the “Dance Your Dissent” workshop in the Plavin Studio. That’s Gavin Schuerch ’18 of Norwalk, Conn., at left and Jorge Piccole ’18 of Middleton, Mass., at right.

The workshop was led by Kiki Ely, a hip-hop dancer and choreographer from Atlanta. She has more than 20 years of teaching experience and has toured with Christina Aguilera, Ciara and Christina Milian, and choreographed for Nelly, Ludacris and Ciara.

8:14 p.m. Monday, Jan. 19

Isaiah Rice ’15 of Dallas, Texas, performs “Italy” during the annual MLK Day performance by the student group Sankofa.

An original production each year, this year’s edition told the story of a fictional African American woman, Evelyn Ola Johnson, who is a world-traveling journalist committed to exposing injustices against peoples of the African diaspora. “This is a bit of all of our stories,” explains Olivier Brillant ’17 of East Orange, N.J., who co-directed the show with Annakay Wright ’17 of Brooklyn, N.Y. “None of this happens to all of us, but it happens to some of us, and we all relate to it.”

The show’s theme underscored the need to share stories in order to foster understanding and, more importantly, to take control of the African American narrative in this country, which was seized by the media during coverage of events in Ferguson, Mo., and New York City. “We need to tell this story because we need to give a voice to the voiceless, which is what Evelyn’s goal was in her life,” Wright says. — Becca Carifio ’15

9:03 p.m. Jan. 19, 2015

Taking questions following the Sankofa production of Black Voice: The Life of Evelyn Ola Johnson, are, from left, Rakiya Mohamed ’17 of Auburn, Maine, Olivier Brillant, Annakay Wright, and Alex Bolden ’15 of Cleveland.

Brillant says that the annual production gives “a little definition to all of us. You walk your daily life, seeing people, but you never know who they are. You may say ‘Hi’ to them. But I feel like you don’t really know someone until you hear their story.

“Sankofa is a bit of all of our stories. None of this happens to all of us, but it happens to some of us, and we all relate to it.” — Becca Carifio ’15

1:51 p.m. Jan. 21, 2015

Bates men’s lacrosse coach Peter Lasagna shares the children’s book Hope’s Gift, about the Emancipation Proclamation, with fourth graders at the Martel School in Lewiston. Volunteers from Bates and Lewiston-Auburn College spent time at the school, sharing a book with students and donating the book in the process. Lasagna read to students, engaged them in discussion, and then asked them to read to each other. — Phyllis Graber Jensen