China’s social-media censors quicker than previously thought, Auer’s research reveals

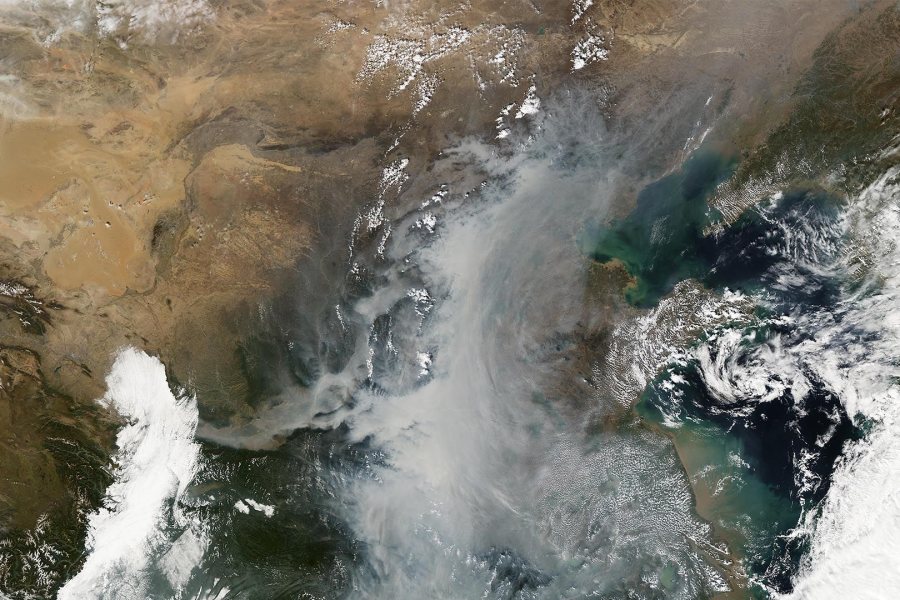

The milky white and gray at center of the image shows smog and fog event over China. The brighter whites at left and right are clouds. (NASA Earth Observatory)

Within two days of its online debut in China last February, the environmental documentary film Under the Dome had been viewed more than 100 million times in that country.

The film also lit up social media, racking up nearly 300 million mentions on Sina Weibo, China’s version of Twitter.

The film exposed how the Chinese government and big state-backed companies are driving China’s air pollution to deadly levels. State-run newspapers praised the film, and China’s minister of environmental protection called it his country’s Silent Spring.

The robust national conversation was surprising, given China’s history of cracking down on dissent and its penchant for silencing critics. The free exchange of ideas, however, didn’t last long.

Stern warnings to media outlets to curtail coverage and commentary on Under the Dome came about a week after its debut. Not long after that, the TED-like video began to disappear online, and newspapers deleted their earlier coverage and commentaries.

But while The New York Times, BBC and other influential news outlets reported on the censorship, nobody, it seemed, had noticed that censors had moved against Sina Weibo users even before they issued their first censorship directive.

“The government’s tolerance of dissent in this case was pretty limited, and there was an uptick in the energy and ambition of the censors versus what we normally find.”

A new report co-authored by Bates Dean of Faculty Matthew Auer in this fall’s issue of the journal Index on Censorship pulls back the veil for the first time on the social media censorship surrounding Under the Dome.

Auer is an environmental policy expert who has published widely in the areas of climate change politics, sustainable forest management, and foreign aid.

By tapping into “metadata” attached to Sina Weibo posts, Auer and King-wa Fu, an associate professor at the University of Hong Kong, were able to document that government censorship related to Under the Dome had begun much earlier than anyone had realized.

Co-authored by Dean of Faculty Matthew Auer, a report in Index on Censorship pulls back the veil for the first time on the social media censorship surrounding Under the Dome.

As Auer and Fu examined the Weibo data, two primary patterns emerged.

First, digital images that showed citizens protesting the state’s role in polluting were censored shortly after they were posted by users.

Second, narrative posts that were condemnatory and that also mentioned the state, were taken down.

“The fact that they took down images of people protesting is no surprise at all,” Auer says. “We’d expect them to be sensitive to that because demonstrations are thought to be direct threats to public order and the power of the state.”

So while the Chinese government has “an allergy to people trying to challenge authority,” Auer says, “nevertheless, this was a remarkable moment because there was this appearance of openness on the part of the government in allowing this video to go forward.”

The work done by Auer and Fu also found many examples of censors taking down posts that were merely sarcastic or mildly critical of the government. Those kinds of posts are often left alone, Auer said.

“The government’s tolerance of dissent in this case was pretty limited, and there was an uptick in the energy and ambition of the censors versus what we normally find,” Auer says.

And there’s evidence that the government also monitored the social media conversation to identify targets for arrest. Auer said he later saw European press reports that identified some of the arrestees, including people appearing in censored digital images.

Auer’s research partner, Fu, is one of the leading experts on social media in China and teaches at the Journalism and Media Studies Center of the University of Hong Kong. He oversees the “Weiboscope” project that used the platform’s backend computer code to track the activity of influential microbloggers in China.

There’s evidence that the government also monitored the social media conversation to identify targets for arrest.

Social media’s power to convene like-minded people virtually, as well as the digital breadcrumbs left behind by the postings, make for rich research material. This has been evident with the role social media played in the Arab Spring and in the Black Lives Matter movement.

Auer said he sees great potential in using social media as a window into the minds of Chinese citizens relating to environmentalism and climate change, two global issues that are greatly influenced by policy decisions inside China.

“In China in particular, you have a country that, based on people’s decisions and habits – so goes the planet” environmentally, Auer says. “The extent that you can detect people’s thoughts about climate change through social media, and see how messages are shaped and opinions are formed — there is increasing research interest in these questions.”

While Auer recognizes the opportunity social media presents for research purposes, it’s somewhat ironic that he personally avoids social media.

He’s not on Twitter, doesn’t have a Facebook account and has, thus far, also eschewed LinkedIn.

“I’m almost like the doctoral student in the theology program who’s an atheist,” Auer said with a smile, adding “I’m exploring user-behavior on social media, but not really using it myself.”