Presidential History

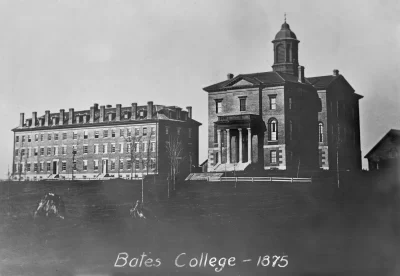

Since 1855

Bates College is a coeducational, nonsectarian, residential college with a commitment to academic rigor, to preserving the dignity of each individual, and to providing access to its programs and opportunities to qualified learners. Bates prizes both the inherent value of a demanding education and the significance of learning, teaching, and understanding.

Bates was founded nearly 170 years ago by people who believed strongly in freedom, civil rights, and the importance of higher education. The school is devoted to undergraduate education in the arts and sciences, and to a culture grounded in teaching excellence.

A champion of inclusion, Bates was the first coeducational college in New England, admitting students without regard to race, religion, national origin, or gender. Student organizations are open to all at Bates, and there are no fraternities or sororities.

Our Presidents

Garry W. Jenkins

Unanimously elected as Bates’ ninth president on Feb. 27, 2023, Garry W. Jenkins officially took office on July 1, 2023.

Jenkins came to Bates after serving as dean of the University of Minnesota Law School for seven years. Prior to that, he was professor of law at the Ohio State University Moritz College of Law, where he also served as associate dean for academic affairs for eight years.

Throughout his career Jenkins has proven to be an innovative and dynamic leader. As dean of the Minnesota Law School, he helped improve the school’s overall ranking, its academic quality, and the diversity of the student body — reaching record highs in all areas. He expanded experiential learning by creating new law clinics in areas such as racial justice and gun violence prevention. He improved student employment and bar passage outcomes and increased resources for student mental health and wellbeing. He also completed one of the largest fundraising campaigns in the school’s history.

At Moritz, Jenkins co-founded and directed the Program on Law and Leadership, one of the first programs in the nation to teach law students the skills and dimensions of leadership. In 2014, he was named the school’s John C. Elam / Vorys Sater Professor of Law.

Jenkins graduated from Haverford College, where he was a Charles A. Dana Scholar. He earned a master’s degree in public policy from the Harvard Kennedy School and a juris doctorate, cum laude, from Harvard Law School, where he was the editor-in-chief of the Harvard Civil Rights-Civil Liberties Law Review.

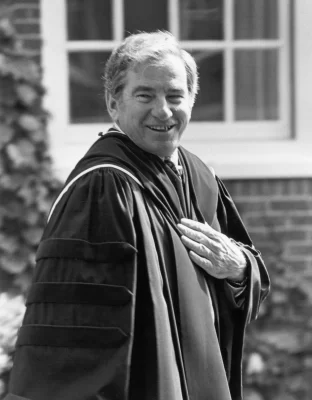

2012–23 | A. Clayton Spencer

As the college’s eighth president, from 2012 to 2023, Clayton Spencer identified the forces shaping society and higher education and found opportunities for creative action. Under Spencer, Bates strengthened its reputation as one of the nation’s leading liberal arts colleges by making strategic improvements in existing and emerging areas of the Bates enterprise:

- Centering equity and inclusion as animating values in Bates’ curriculum, teaching, student life, and the daily work of everyone at the college

- Expanding the faculty and increasing the successful recruitment and support of faculty members from traditionally underrepresented groups

- Designing Purposeful Work, a nationally known program rooted in the liberal arts to prepare students for lives of meaning and purpose

- Adapting and adding to the physical infrastructure at Bates, including two new residence halls and a $75 million investment in STEM facilities

In teaching, learning, and research, Bates established itself as a leader in pursuing innovative and equity-driven approaches designed to remove barriers to student learning and improve the academic experience for all students. The college established seven new endowed professorships: three to support a new Program in Digital and Computational Studies; three in economics, neuroscience, and chemistry; and a seventh dedicated to equity and inclusion in STEM. In addition to expanding the faculty, the college worked hard to increase recruitment and support of faculty members from traditionally underrepresented groups. From 2018 to 2023, the college hired 34 new tenure-track faculty, half of whom identify as BIPOC.

During her tenure, Bates completed the largest fundraising campaign in the college’s history, raising $345.7 million in gifts and pledges. Bates invested over $75 million to create Bonney Science Center, renovate Dana Chemistry Hall, and improve Carnegie Science Hall. In addition to state-of-the-art labs, these facilities also offer modern classroom and collaborative study spaces for all disciplines.

Additional strategic infrastructure improvements extended the college’s identity and resources along Campus Avenue, including Bonney Science Center, Chu and Kalperis residence halls (the latter a mixed-use facility incorporating the College Store and the college’s Post & Print operation), and the renovation of historic Chase Hall, completed in fall 2023, creating a new nexus for student programs and services.

During Spencer’s tenure, admission applications increased by 67 percent, and Bates deepened its commitment to financial aid, strengthened programs for first-generation students, and expanded the percentage of enrolled students who identify as Black, Indigenous, or people of color by 56 percent. In 2021, Bates was chosen as one of the first five colleges to participate in the Schuler Access Initiative, which will generate up to $100 million over the next 10 years to expand the number of talented students at Bates from America’s lowest income families.

Bates’ approach to student development, manifested as the Bates Center for Purposeful Work, drew national recognition under Spencer. Rooted in the core principles of the liberal arts, the program has curricular and co-curricular aspects and takes a four-year, developmental approach to working with students. The concept of purposeful work is based on the premise that meaningful work, however each individual defines it, is fundamental to shaping a life; the Bates program helps students determine how to navigate the evolving worlds of work based on developing their own sense of identity, agency, and purpose.

2011–12 (interim) | Nancy J. Cable

Nancy J. Cable assumed duties as interim president of Bates on July 1, 2011. She served in that capacity until July 1, 2012, when she returned to a position as a vice president, also serving as senior adviser to the eighth president, Clayton Spencer.

Cable joined Bates in early 2010 as vice president and dean of enrollment and external affairs, with responsibility for strategic enhancement in admission, financial aid, career development, and college communications, marketing and positioning.

On Oct. 22, 2012, the Arthur Vining Davis Foundations announced Cable’s appointment as its president, effective in the spring of 2013. Based in Jacksonville, Fla., the foundations were established in 1952 by industrialist and philanthropist Arthur Vining Davis and are dedicated to supporting education, theological education, public television, and health care.

In addition to the A.V. Davis Foundations appointment, with the support of the foundations’ board of trustees, Cable traveled to China as a Fulbright Specialist. In Hong Kong she worked with a team of scholars on developing liberal arts education in China.

Cable has built a national reputation in higher education, compiling a distinguished record of senior leadership at highly regarded colleges and universities and in various national higher education organizations, including Guilford College, Davidson College, and the University of Virginia.

2002–11 | Elaine Tuttle Hansen

Elaine Tuttle Hansen became the college’s seventh president in 2002 and served until 2011. A former professor of English and provost at Haverford College, she worked to enhance Bates’ trademark strengths: open and intense intellectual inquiry; individualized student and faculty interactions in a historic residential setting; and a community unified by the ethical principles of integrity, egalitarianism, and social responsibility.

During her presidency, the college developed greater resources for financial aid, increased diversity of the faculty and student body, strengthened environmental sustainability and stewardship, and made technological advances. Hansen undertook a range of institutional planning initiatives, including facilities master planning and academic planning.

Under Hansen, a collaborative process of strategic thinking about Bates’ future prompted the college to pursue a deeper integration of ideas and practices in the areas of arts, natural science and mathematics, and learning across the entire Bates’ experience. Hansen appointed teams of faculty and administrators to lead the work for each major component of the plan.

By 2011, Hansen guided Bates through Phase I of its ambitious Campus Facilities Master Plan. A new residence hall for 150 students at the foot of Mount David opened in August 2007. A new Dining Commons opened in February 2008, preserves the Bates tradition of centralized student dining. The renovation and expansion of historic Roger Williams Hall and Hedge Hall, completed in 2011, created new academic facilities including state-of-the-art classrooms, faculty offices, study areas, computer labs, lounges, and administrative spaces.

With a wide array of goals for her administration accomplished, Hansen announced in spring 2011 that she would step down from the Bates presidency at the conclusion of that academic year. She subsequently accepted the position of executive director of the Johns Hopkins University’s Center for Talented Youth. As the third person to lead CTY since its founding in 1979, she continued her leadership in the field of education and her commitment to helping young people with outstanding academic capabilities fulfill their potential.

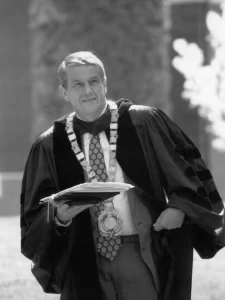

1989–2002 | Donald West Harward

In 1989, an observer of the Thomas Hedley Reynolds presidency noted that Bates was somewhat isolated geographically and by temperament. Could the next president, it was asked, open Bates up to the challenges and problems facing the rest of the world?

As Bates’ sixth president from 1989 to 2002, Donald West Harward answered that question by affirming the important idea that “learning is a moral activity that carries responsibility beyond the self.” Harward helped Bates see how traditional college values of egalitarianism and social justice created a moral imperative to connect academically to the world beyond Bates. Students achieved greater opportunities to study and conduct research off campus and with their professors, and the capstone thesis program enjoyed greater integration with the rest of the academic offerings.

Harward oversaw the creation of two dozen new academic programs, giving faculty the proper resources to investigate new emerging questions that bumped up against traditional disciplines.

“You can’t just study the molecular structure of a substance,” he would say as an example, “without learning about the people who might be using the substance to create things that can destroy our environment.”

Under Harward, Bates reached out institutionally to the Lewiston-Auburn community for the first time in many years. Bates faculty and students built relationships with the community through one of the most active service-learning programs in the country. While upholding the notion that a college’s intellectual activity must remain, for the most part, cloistered, Harward helped Bates provide a national model for ways colleges and universities can still connect to and support their local communities.

Bates’ infrastructure saw major improvement during the Harward presidency with the planning and building of 22 essential academic, residential and athletic facilities. These include Pettengill Hall and its Perry Atrium, the Bates College Coastal Center at Shortridge, Dunn Guest House, Keigwin Amphitheater and the Lake Andrews restoration, the Residential Village, Benjamin E. Mays Center, Wallach Tennis Center, John Bertram AstroTurf field, track and soccer field, softball field, Underhill Arena and the Davis Fitness Center.

1967–89 | Thomas Hedley Reynolds

When Thomas Hedley Reynolds retired after serving as Bates’ fifth president from 1967 to 1989, he was able to boast that all but 16 of the 159 faculty members were appointed during his presidency. While key facility improvements also marked his tenure at Bates, his work as a champion of the faculty was perhaps his greatest achievement.

“President Reynolds has given us more time, more colleagues, and perhaps above all else, more self-esteem,” said John R. Cole, a member of the history faculty, in 1989. “The result is that a good college of good teachers has become a better college of better teachers.”

Toward that end, Reynolds emphasized the need to improve salaries to attract and retain high-quality faculty. Bates achieved greater gender equity during the Reynolds years, as well as an improved faculty-student ratio and an average class size of 15.

Furthermore, Reynolds also encouraged closer faculty involvement in the governance of the college through elected committees as well as the expansion of the sabbatical program. His own experience as a teacher and a scholar allowed Reynolds to recognize teaching and scholarship as complimentary professorial activities (previous administrations had viewed the two as generally antithetical), leading Reynolds to encourage faculty research and creativity.

Arriving at Bates during a tumultuous time for U.S. colleges, Reynolds also faced the rancor of students who were upset by strict campus social rules that reflected the sensibilities of the 1950s. In response, he guided the college through the campus tensions of the late ’60s and ’70s with a renewed emphasis on involving all members of the community in making decisions.

Significant renovations and physical additions to the campus under Reynolds include the George and Helen Ladd Library, Merrill Gymnasium and Tarbell Pool, the Olin Arts Center with its Bates College Museum of Art, the conversion of the former women’s athletic building into the Edmund S. Muskie Archives, and the acquisition of the Bates-Morse Mountain Conservation Area. The houses on Frye Street, a popular and creative residential alternative to traditional dormitory housing, were also acquired primarily during the Reynolds presidency.

President Emeritus Reynolds died Sept. 22, 2009.

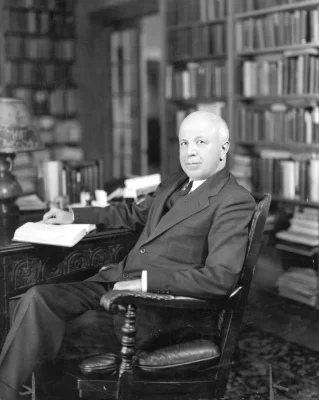

1944–67 | Charles Franklin Phillips

Charles F. Phillips was a full professor at Colgate and a leading economist before coming to Bates as the college’s fourth and youngest president. He was 34. He also taught at Hobart College, and at the time of his interview at Bates was on leave from Colgate and working for the U.S. government in the Office of Price Administration and Civilian Supplies as deputy administrator in charge of rationing.

At Bates, Phillips initiated the Bates Plan of Education, a liberal-arts “core” study program, and developed the “3/4 Option” which allowed students to complete their college education in three years if they desired. He also saw the campus expand with the additions of Memorial Commons, the Health Center, Dana Chemistry Hall, Lane Hall, a new Maintenance Center, Page Hall, Pettigrew Hall, Treat Art Gallery, and Schaeffer Theatre. Phillips also added full-time administrators to the college staff: an alumni secretary, a director of admissions, a dean of men and an assistant to the president.

Known for bridging the gap between the academic and business worlds, Phillips won many friends for the college, and often encouraged young graduates to start their own business, rather than joining a big company. Convinced that American economic and political systems thrived on competition, Phillips applied this theory to Bates and its graduates. In his inauguration address he quoted Edison: “Genius [required to make it big] is 1% inspiration and 99% perspiration.” During his time at Bates, Phillips lived by this adage —he was famous for keeping a tight schedule, with or without a clock, and for working late hours.

Phillips retired in 1967, leaving a student body of 1,004 and an endowment of $6.9 million. He lived in Auburn after retirement and passed away in 1998.

1920–44 | Clifton Daggett Gray

As the college’s third president, Clifton Daggett Gray, clergyman and former editor of Chicago’s The Standard, saw Bates through an era marked by vibrant growth, the Great Depression and World War II.

In the early 1920s, Bates debating went international; Libbey Forum and Hedge Laboratory were renovated; and the Clifton Daggett Gray Athletic Building and Alumni Gym were built. Then, in 1929, the stock market crashed. Students became hard to find. Who could afford the annual $600 tuition? The result was a year in the red. Yet the financial difficulty did not last long.

When World War II came — Bates responded. Gray arranged for a V12 Naval Training Unit on campus, assuring the college was populated with good students during wartime while other colleges were feeling the draft. Ninety Bowdoin students came upriver to Bates for the V12 program.

By the time he retired in 1944, Gray had increased student enrollment from 527 to 749, faculty from 36 to 70, and the endowment from $1 million to $2 million.

1919–20 (acting) | William Henry Hartshorn

Following the May 1919 death of President Chase, faculty member William Henry Hartshorn served as acting president for nearly a year until the appointment of Clifton Daggett Gray, whereupon he returned to his teaching duties. A member of the Bates Class of 1886, Hartshorn taught at his alma mater for 37 years. He began his Bates career in 1889 as an instructor — later professor — of physics and geology, and in 1894 he became a professor of English literature, a position he held until 1926.

Hartshorn was one of the most beloved Bates professors of his day, was affectionately known by his students as “Monie.” In addition, the Class of 1923 dedicated their senior edition of The Mirror to him.

On the morning of Feb. 24, 1926, just before the start of the day’s classes, Hartshorn died at his classroom desk and was found by his students, sitting with his copy of Paradise Lost open to that day’s lesson. After his death, a testimonial to Hartshorn appeared in The Bates Student, attesting to the love his students felt:

“[H]is perspective on life was not a relic of other days. He understood our present generation of students as well as he understood the generation of 30 years ago. Some professors are appreciated only after they are gone. Not so with ‘Monie.’ Human and fair in all his dealings with his students, he was the bedrock upon which Bates men and women could base their ideals.”

1894–1919 | George Colby Chase

George Colby Chase graduated from Bates in 1869 and taught for 22 years as professor of English at the college before he became the college’s second president.

Chase, known as “the great builder,” oversaw the construction of 11 new buildings, including Coram Library, Rand Hall, the Central Heating Plant, the Chapel, Libbey Forum, the Carnegie Science Hall, and Chase Hall; he tripled the number of students and faculty; and he managed to increase the college’s endowment from $259,000 to $1,135,000.

Chase was known for being “fanatically frugal” and money-conscious. When he went on fundraising trips, he often had his son take his trunk on a wheelbarrow to the railroad station. When the faculty said they thought students should bear more of the cost of their education, he reluctantly approved a $5 tuition increase (Bates trustees later voted to raise the cost $15, making tuition $90).

A teacher-president in the old tradition, Chase taught at least one course throughout his entire tenure. His home at 16 Frye St. functioned as a campus facility where students would go for their admission interviews, various progress checks, and, upon graduation, letters of reference.

In April of 1919, at age 74, Chase wrote to the trustees regarding his retirement and the selection of a new president. His successor, he said, was to be “a man strong in scholarship, in his Christian character and influence, in business ability, and in warm sympathy with young people . . . and hopefully not older than 35.” On May 27, 1919, after a full day at work, George Colby Chase died of a heart attack.

1863–94 | Oren Burbank Cheney

The Rev. Oren Burbank Cheney was the founder and first president of Bates College. He was a Freewill Baptist minister, a teacher, and a former Maine state representative. In 1854 the Parsonfield Seminary, a school at which Cheney had been a student and a teacher, burned down. Seeing a need for a new, larger, and more centrally located school for his denomination, Cheney steered a bill through the Maine Legislature in 1855, creating a corporation for educational purposes called initially “Maine State Seminary.”

According to Bates history, the two existing Maine colleges, Bowdoin and Colby, were confident they could offer all the higher education the state needed. But Cheney persevered. He assembled a faculty of six who were dedicated to teaching the classics and moral philosophy, and in 1863 received the collegiate charter. In 1864 the Maine State Seminary became Bates College. The College consisted of Hathorn and Parker halls, and the student body numbered fewer than 100.

At the end of Cheney’s tenure, tuition was $36 a year, the library contained 16,500 volumes, and the campus included six buildings across 50 acres. Bates was known for a nondiscriminatory liberal education that even was made available to students of limited financial means, and for “doing great work for the state of Maine in educating teachers for its public schools.”

You can learn more about each of Bates’ presidents at the Past Presidents website and more about Bates History on the 150 Years website.