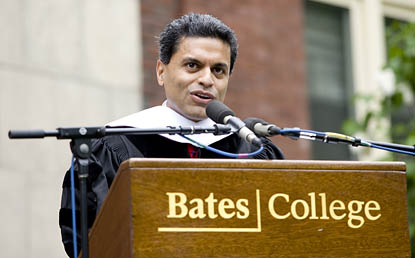

Address by Fareed Zakaria

Unedited transcript, subject to change and correction, of Commencement 2009 remarks by Fareed Zakaria, who received the honorary degree Doctor of Humane Letters.

Thank you so much, Michael [Chu ’80, citation presenter]. Thank you Madame President. I gather that there is a Bates College tradition of staying up all night before this morning. I can tell why so many of you have dark glasses on even though there is no sun [laughter]. I must have been a Batesie in a previous life, because the night before my college graduation, I fulfilled this Bates College tradition, but alas did not make it to my commencement ceremony, so I am deeply impressed by all of you being here today [laughter and applause].

https://youtu.be/aCKQcxdyhm4

It’s a little bit tough for me despite those very kind words that Michael Chu said. I’ve never really thought of myself as being at the advice-giving age yet. I find this a little more difficult to do than one would imagine.

There’s this wonderful scene in Woody Allen’s Radio Days. The young Woody Allen is listening to the radio and the mother is horrified to see this. The mother says, “Stop listening to the radio. It’s going to ruin you.” This was in the day that people thought that Cole Porter and Gershwin were bad for your moral health. Woody Allen looks at her and says, “But Ma, you listen to the radio all day. ” And she says, “Ah, that’s different. My life is ruined already.” [laughter]

My life is not quite ruined yet, so I’m a little reluctant to give you advice. We face a difficult period for those of us out in the world. Art Buchwald once gave a very short graduation speech. He said, “Ladies and gentlemen. We’re leaving behind a perfect world. Don’t screw it up.” [laughter]

I think it’s difficult for any of us to make that claim to you right now. We are going through a very difficult time. Whether it is geopolitically or economically, clearly these are awkward and difficult moments for you to graduate in to. But let me tell you why I remain very optimistic, and this is the short message I want to leave you with.

I remain extremely optimistic about the world you are going into and your opportunities because of you. This entirely relates to change, something Geena Davis began talking about. Let me give you one example. About a month ago, the World Health Organization declared that there was a global pandemic relating to swine flu and warned that there would be deaths probably in the hundreds of thousands. As of now we have had as many deaths and confirmed infections as from a normal seasonal case of influenza. Why is that?

Is it because we all panicked and got it wrong? No, the swine flu had many characteristics of a virus that led one to be very troubled. But what happened was that the World Health Organization issued its warning and people acted. People acted fast and energetically, particularly fast and energetically in the epicenter of the crisis, in Mexico. The Mexican government basically quarantined everyone who had the disease, inoculated those who it could, provided drugs for most people, which was the most effective treatment. Most importantly, it shut down its areas of common meeting places, shut down its economy for virtually three weeks in order to stop the progress of this flu. It seems that by doing that they largely stopped the virus in its tracks.

The point I’m trying to make is that we can all very easily describe the problems that the world faces — economic, environmental, geopolitical — but what is always very difficult to describe is the human response to the problems. In the 1760s, an English clerk, Thomas Malthus, predicted that England would run out of food and that its population would starve in a famous essay called, “The Essay on Population.” Malthus was entirely right in describing the problem. He did not understand the human response. England invented an agricultural revolution, then an industrial revolution, went on not simply to feed its people but a large part of the world.

If you look at the current economic crisis, we can all describe all the problems we face. But it is very difficult to know what you will do in response to it. What we will do in response to it. What government will do, what industry will do, what nonprofit organizations will do, and how the collective human response will thus change history.

If you look at the last 200 or 300 years, it is a story of challenge and response. And it is much easier to describe the structural challenges we face than to describe the human response to those challenges that will change history.

So if you ask what the future holds, I don’t know because I don’t know what you will do. And it really is up to you to decide what you are going to do. But you will do something because in every small way that you act, you act as productive economic beings, as moral beings, as social beings, and in all those actions, when collected together you change history.

That is my simple message to you. Recognize that you are the change you seek. You are the great agents of change in the world. When you look at all these forces — the rise of China, the rise of India — whatever it is, remember you can adapt to them. You can embrace them. You can respond to them in ways that will better your life, better the life of your society. You cannot ignore them. You cannot fight them. But what you can do is adapt and make the world a better place.

It is an extraordinary moment to be coming into the world because in the first time in human history people around the world are achieving some level of human dignity in terms of their rise out of poverty. If you would have asked me 30 years ago how many countries were growing at 4 percent a year, that number would have been about 30. Today it is about 130. You have an extraordinary new world out there with all kinds of human talent being unleashed.

To have that money people consuming, producing, investing, dreaming, singing, praying — this has to be a good thing. It’s a world that is ultimately going to have many more opportunities than the world I grew up in and that my parents grew up in.

What does this mean in terms of what industry you should go into? I don’t know. I don’t know whether nanotechnology or biotechnology is the wave of the future. I don’t know if you should become investment banks or artists. Investment banking isn’t looking so hot these days though [laughter].

But I will tell you something very simple and obvious, which is that it is likely that human beings will find fulfillment and will be rewarded for the same qualities that they have been rewarded for for 5,000 years. And that is intelligence, hard work, honesty, a sense of character, loyalty to family and friends, and above all love and faith.

If you are trying to decide what you should do, those are the things you should do. And you know it. The difficult thing is acting on them. I leave you with that simple advice. If you are trying to figure out what to do in the future, for 5,000 years people have built statues to men and women who have had those characteristics. They are likely to do the same, or they won’t build statues anymore. They’ll build weird modernist pieces of art, mobile sculptures with strange do-dads on them. You get the general point [laughter].

Ladies and gentlemen of the Class of 2009, God speed.